LNG | Infrastructure | International | LNG Insight | Markets | Natural Gas Prices | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

War Cuts Long-Term Demand Outlook as Europe Looks to Expedite Move Away from Natural Gas

European energy prices have hit records since Russia invaded Ukraine, but as warmer weather nears, concerns are shifting to how the continent can cope with natural gas shortages next winter if the conflict drags on and what it means for longer-term demand in the region.

“The coming of spring certainly makes it easier to live without Russian gas,” Nikos Tsafos, an energy expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told NGI. “But you have to think about next winter, too. Without Russian gas, you’re in real trouble.”

The prospect has opened the floodgates for a variety of scenarios about how Europe could manage without Russian natural gas, its largest supplier, if the Kremlin cut flows to the continent or the West decides to impose harsh sanctions on Russian energy exports.

In that case, Europe would be forced to rely more heavily on a mixture of liquefied natural gas (LNG), pipeline imports from other suppliers, energy conservation efforts, more domestic production and other resources such as coal and nuclear.

The European Union (EU) is girding for the possibility of a complete cut in Russian pipeline imports in retaliation for the sanctions the West has already levied on the country. Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak reportedly said Monday that Russia has “every right” to stop gas flowing to Germany via Nord Stream 1 in response to the West’s sanctions. He added, however, that the country has not made that decision.

European energy commissioner Kadri Simson has said the EU is prepared for a number of outcomes. The bloc’s executive branch is also drafting a plan to enhance its energy resilience and cut its dependence on foreign fossil fuels.

“The result of recent events will not just mean less Russian gas, it will also mean less overall demand as Europe looks to accelerate a move away from natural gas,” said Wood Mackenzie’s Mauro Chavez Rodriguez, research director for gas and LNG markets.

“We certainly see an upside for LNG imports in Europe and high gas prices to attract cargoes as the market will be tight for longer,” he told NGI, “but perhaps less LNG demand than many would hope for, particularly in the long term as gas demand will continue falling in Europe.”

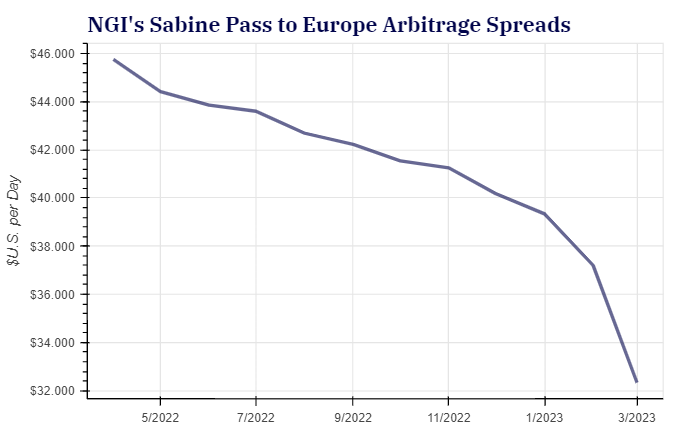

In the nearer-term, LNG demand is poised to rise. Imports of the super-chilled fuel have surged over the last three months and the bulk of those cargoes have come from the United States. That’s not likely to change anytime soon given the wide spread between European and Asian prices.

[Download Now: In our 2024 Natural Gas Outlook Report ‘Future In Focus’, Natural Gas Intelligence’s experienced team of Thought Leaders delve into the myriad opportunities and questions the industry faces, with a focus on market dynamics, upstream outlooks and price forecast trends that will shape the future global natural gas landscape. Learn more.]

European cargo diversions are already maxed out, said Oystein Kalleklev, CEO of shipper Flex LNG Ltd.

“So, it’s more that the uncertainty given the situation in Ukraine is creating more risk and this gets baked into the price of gas in Europe,” Kalleklev told NGI. “And as long as this endures, we will see Europe the marginal cargo buyer and therefore also muted arbitrage to the East.”

LNG is factored heavily into a 10-point plan released by the International Energy Agency to help Europe cut reliance on Russian natural gas by roughly one-third over the next 12 months. The blueprint calls for a 20 billion cubic meter (Bcm) increase in LNG imports over the next year. The IEA also noted that the EU has the capability to ramp up LNG imports by 60 Bcm, given its ample regasification and pipeline capacity.

But boosting LNG purchases at current prices, assuming the continent can continue to attract flexible cargoes as competition with Asia will continue increasing, is a costly proposition. To refill storage to average levels utilizing LNG would cost nearly $80 billion at current prices, according to the Belgium-based think tank Bruegel.

The think tank recently laid out various scenarios for how the continent could cope without Russian gas supplies, saying there are “no simple answers.” It suggested, however, that in theory the continent could live with less Russian gas, or none at all.

In addition to other measures, if Russia were to completely cut off supplies, Bruegel said Europe would also need to reduce annual gas demand by 10-15%.

In the event Europe is forced to adapt to such a reality, “dozens of regulations will have to be revised, usual procedures and operations revisited, a lot of money quickly spent and hard decisions taken,” Bruegel said. “In many cases time will be too short for perfect answers.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |