Natural Gas Prices | E&P | LNG | LNG Insight | Markets | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Shale Daily

U.S. Natural Gas Prices Reflect ‘Amply Supplied’ Market This Winter, but Optics Less Clear in South Central

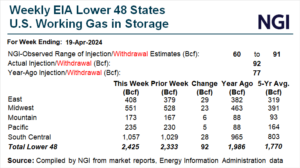

Record power burns and elevated gas exports have halved the surplus of Lower 48 working gas in storage since the summer. However, with an expected loosening of supply/demand balances, supply risks are unlikely this winter except in the most severe cold weather scenarios, according to analysts.

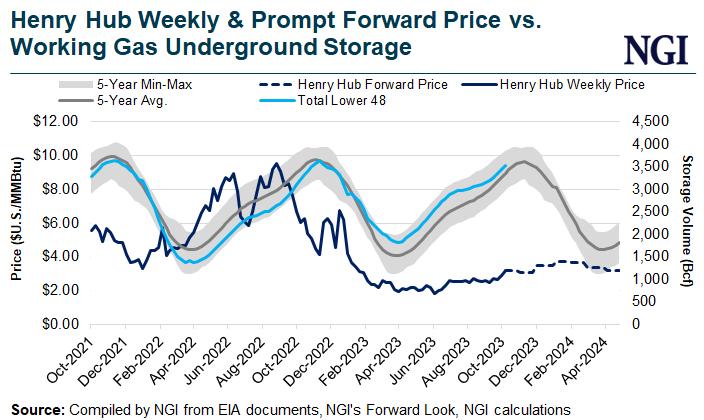

The storage surplus to the five-year average has fallen to 163 Bcf from a June peak of 370 Bcf, a narrowing punctuated by a surprisingly lean Energy Information Administration (EIA) storage reading on Oct. 5 that sent gas futures above the $3.000/MMBtu level for the first time since January.

The rally has largely continued since then, with the rise in prices extending through the 2023-2024 winter strip. Henry Hub forward prices for November-March averaged $3.563 as of Oct. 12, up 23 cents in two weeks, according to NGI’s Forward Look.

Last winter, Henry Hub cash prices averaged $3.762, according to NGI data. Prices started the season strong, rising above $6.000 in November and $7.000 as Winter Storm Elliott slammed the United States in late December. But a mild January followed and prices slumped 73% from the high to end the winter below $2.000.

Ahead of the upcoming winter, the October-January futures spread widened to around $1.20, some of the steepest contango in the curve seen in the shale era, according to Mobius Risk Group. Those spreads have narrowed in recent weeks, with October cash trading around $3.000 and January forward prices at around $3.800.

“What you’ve seen more than anything so far is not necessarily a wholesale appreciation in price as much as you’ve seen some of the historically steep contango begin to dissipate,” Mobius natural gas analyst Zane Curry told NGI.

“At the same time, the market is beginning to acknowledge how quickly the storage surplus in the South Central has eroded, and particularly the surplus in salt storage,” according to Curry.

The EIA’s South Central region had a storage surplus of 38 Bcf to the five-year average in the week ended Oct. 6, down from a peak of 239 Bcf in April, which is the official start of summer in the natural gas market. Salt’s surplus fell to 5 Bcf from a peak of 59 Bcf in July.

[Mexico Matters: Cross-border energy trade between the U.S. and Mexico reached $82 billion last year. Understand this burgeoning trade flow — the projects, politics and natural gas prices — with NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index. Know more.]

“Salt storage is the canary in the coal mine for congestion or lack thereof,” Curry said. “If there’s space in salts, then you can make it through a mild early November or even a mild early December” when nonsalt storage facilities move into withdrawal mode only.

With only weeks to go before the end of the traditional injection season on Oct. 31, analysts expect storage to top out at around 3.8 Tcf. That’s well short of fears held before the summer that stocks could swell above the critical 4 Tcf level by the end of the injection season.

“The market began the spring with expectations of an oversupplied inventory constrained dynamic presenting itself at the end of summer 2023 that looked like a 4 to 4.2 Tcf end-of-October inventory level,” Curry said. “And what happened next? The simple math is 300 Bcf disappeared from market expectations.”

What Factors Limited Injections?

The biggest factor behind the surplus drop was this year’s record power burn, according to RBN Energy LLC analyst Sheetal Nasta.

April to October-to-date demand for natural gas rose by 3.5 Bcf/d year/year against a 3.0 Bcf/d increase in supply from the previous year, Nasta said. Power burn accounted for 2.8 Bcf/d of that increase, followed by LNG exports at a 1.2 Bcf/d gain and Mexico exports up by 0.7 Bcf/d.

While this past summer was a sweltering 15th hottest on record, it was not as hot as the previous summer. Instead, coal-to-gas switching and low wind generation drove market share gains for gas, according to Nasta.

Through August, coal generation lost about 5 percentage points of its share of total power generation, while wind lost 1.5 percentage points, according to Nasta. Coal’s decline is partly because of the retirement of 11 GW of capacity this year, with most of that in the East and set to take place before July.

“Wind was particularly lower than usual during the spring and early-summer months, which helped prop up power burn in those lower-demand months when there’s typically more excess gas-fired generation capacity available,” she said.

At the same time, the Freeport liquefied natural gas terminal regained its full export capacity in April after an early June fire idled it for much of the 2022 summer. Exports to Mexico also strengthened year/year given strong heat and robust cooling demand south of the border.

All these factors increased demand to keep pace with record gas production.

“It was a little bit of a surprise for a lot of people because at the beginning of the injection season, there was a lot of doubt and debate about whether power burn could top what it did last year, which was at records,” Nasta told NGI.

How Low Will Stocks Fall This Winter?

For now, the jury is still out on how weather, robust LNG demand and production may impact storage withdrawals this winter.

EBW Analytics Group analyst Eli Rubin is projecting 1,650 Bcf for end-of-March inventories in a normal winter scenario. The risks to the forecast are tied primarily to weather, but there are a few factors that tilt the odds in a bearish direction, according to the analyst.

“One of those is simply, every year we have winter risk premiums that are baked into the market at the beginning of winter that basically account for the possibility of an extreme cold scenario that completely depletes storage,” Rubin told NGI.

It’s still possible to see price upside, he said. An extreme shot of cold weather and freeze-offs typically raises fears in the market that storage could run down to the key psychological level of 1,000 Bcf. “But again, in the majority of scenarios, the market appears to be amply supplied, weather indications lean in a bearish direction, and we have some additional reserves in Canada to call upon.” He added that gas-to-coal switching also could reduce gas demand.

The strong El Niño weather pattern argues in bears’ favor because it correlates to a warmer-than-normal winter in the northern U.S.

James Bevan, vice president of Research at Criterion Research LLC, is expecting a slightly higher end-of-winter balance of 1,710 Bcf after a 2,100 Bcf withdrawal. This is based on a 10-year normal winter, higher gas burns because of its increased prominence in the stack, rising LNG exports and mostly flat production levels.

“So really strong LNG nominations near 14 Bcf/d or higher, and we think production will start to weaken a little bit in December and January as it tends to in the wintertime,” Bevan told NGI. As far as residential, commercial and industrial demand, “we can make a lot of predictions, but the only thing that really is going to matter is the weather.”

Market expectations have been for a 2 Tcf withdrawal this winter to put the end-of-season storage at around 1.9 Tcf, Curry said. This would be a 250 Bcf increase over last winter’s 1.75 Tcf withdrawal.

A normal winter could add between 150 Bcf to 400 Bcf of gas demand over the previous mild winter, Curry said. Last winter’s mild weather was centered in the East, but a gas-weighted estimate that is biased to other regions gets closer to 400 Bcf of higher demand, he said.

Freeport LNG being back online adds another 220 Bcf of incremental demand, though stronger production would partly offset this higher demand to arrive at the 250 Bcf year/year withdrawal increase, according to Curry.

Production Uncertainty

That said, production can be a wildcard in the case of intense cold in certain regions. While output generally is expected to be higher, last winter’s polar vortex-like storm has led to a new dynamic playing out in the winter strip, especially January and February.

EBW’s Rubin pointed out that some natural gas producers have been reluctant to hedge output after last year’s freeze-offs left them effectively short the market. Producers are natural sellers of the contract because they already have the physical gas, he explained. When producers are hedging their natural gas supply in January, they’re selling a January contract because they have that supply that’s coming out of the ground. Without the same selling pressure in mid-winter contracts, “it can allow your January-February contracts to remain higher than they would otherwise if more people were selling them,” Rubin said.

While Rubin is watching for downside price risks, Curry said there could be an upside surprise if storage proves less prepared for winter.

Not So Rosy In Texas?

One “interesting conundrum” has been the weak storage build in the South Central region in spite of its significant production growth, according to Curry. The region has seen a cumulative injection of only 40 Bcf since late August, just short of the range of 41 Bcf to 188 Bcf over the past decade.

“So we’ve set a new [low] in a period where the wind has not been as weak year/year, where temperatures have not been as extreme in Texas, where LNG has yet to show any material improvement,” Curry said. “In other words, the argument for, ‘Well, it was just heat in Texas,’ begins to lose its ability to hold water.”

More broadly, the Lower 48’s storage surplus is based on a five-year average that includes 2018 that weighs that measure down, Curry said. That year, the injection season ended at a low level of 3.2 Tcf in the ground.

Excluding 2018 would erase much of the current surplus by raising the five-year average closer to 3.7 Tcf instead of 3.6 Tcf by the end of October, he said.

“We see the market being set up for a meaningful surprise in the event that the weather this winter is normal to colder than normal,” Curry said. “And, as we will often say, Mother Nature’s the undisputed heavyweight champ, and she will determine the course of prices through this winter and arguably set the table for 2024.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |