NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

Canol Shale Exploration Drawing Nearer

A new frontier is opening for shale drilling and hydraulic fracturing on a sub-arctic landscape of forests, muskeg swamps and permafrost 2,000 kilometers (1,200 miles) north of the border between western Canada and the United States.

The technology will be given a field trial, lasting up to five years, after the aboriginal authority for environmental policing in the central Mackenzie Valley, known as the Sahtu by its chiefly Dene and Metis inhabitants, granted industry a regulatory breakthrough into the region.

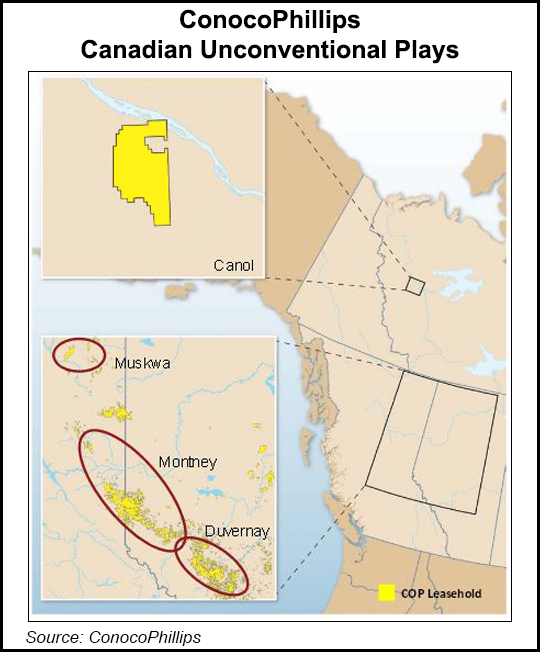

ConocoPhillips Canada turned on the green light for a shale exploration campaign, which is expected to lure other firms into the area swiftly, by obtaining permits this summer from the Sahtu Land and Water Board. In the Canadian oil and gas capital of Calgary, industry insiders say northern specialist MGM Energy and Shell Canada are already making plans for prospects in the region.

The unannounced approval reversed a regulatory decision that froze the controversial technology out of the Sahtu during previous winter drilling seasons. The discarded restriction demanded a full environmental impact assessment for exploration wells using horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing. This is a requirement that takes up to three years to fulfill in northern Canada.

At northern business conferences and in private lobbying, the industry insisted the assessment requirement should only be invoked after initial wells demonstrate that the technology works well enough to embark on large-scale shale production with multiple development wells.

In awarding approval to the ConocoPhillips program, the Sahtu agency settled for a “screening” procedure of reviewing the landscape and wildlife, consulting residents and devising permit conditions briskly without public hearings.

The permits, valid from this June through October of 2017, allow full trials of the advanced technology, including production tests, at two sites on Aboriginal territory southwest of Norman Wells.

The permits and sketchy details of the program were quietly posted on a public registry that the Sahtu agency maintains on its website. Companion approvals by the National Energy Board and the federal Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, covering engineering and local economic benefits aspects, are understood to have been granted or coming soon. Disclosures of northern exploration matters are customarily limited on grounds that confidential commercial knowledge is involved. All results of northern wells can be kept secret for two years after their completion.

Plans disclosed by ConocoPhillips to the native authority call for drilling vertically down as deep as 1,800 meters (5,900 feet) and horizontally for up to 1,500 meters (4,920 feet). Each horizontal leg will be used to blow flow channels into the dense but brittle geological layer with up to 10 hydraulic fracturing injections at a pressure of 8,700 psi. Each frack will use liquid mixtures of water and chemicals at rates of 8,000 to 10,000 liters (2,160 to 2,700 U.S. gallons) per minute, and pump about 100 tons of clean sand into the rock as proppant.

The target is a liquids- and especially oil-rich shale formation known as the Canol, which is named after a pipeline built from Norman Wells west to the Yukon as a U.S. and Canadian defense collaboration during the Second World War. The line provided fuel from a 1920s discovery in the central Mackenzie Valley for army and air forces that stood guard against a feared Japanese northern invasion, and for U.S. fighter and bomber aircraft flown to the former Soviet Union by a wartime lend-lease program.

The pipeline was discarded and the oil wells were sealed after the war. Production resumed in the mid-1980s at a rate of up to about 35,000 b/d, pumped up by artificial islands built in the Mackenzie River and delivered through a pipeline to northwestern Alberta.

While output from the old wells has fallen and the pipeline is only about two-thirds full, Calgary geology, engineering and production firms predict that a shale reincarnation could eventually refill the pipeline — and require construction of another one in its right-of-way — by producing 100,000 b/d or more. A vertical sampling well that MGM and Shell drilled last winter confirmed that the Canol formation is 100 meters (328 feet) thick or more, and also affirmed predictions of liquid wealth by prospecting geologists who report surface outcrops give off a rich oily odor when struck with hammers (see Shale Daily, March 25; Feb. 1).

A Mackenzie Valley lease sale two years ago drew six producers that paid C$534 million to acquire 3,473 square miles of drilling rights (see Shale Daily, July 11, 2011).

The exploration wells, in combination with industrial-scale expeditions needed to drill them, are intended to prove that shale technology developed in Texas can be exported to sub-arctic Canada. “Freeze protection and the ability to work mechanical equipment in cold-weather environments are critical,” says a Canol program description by ConocoPhillips.

From the Sahtu point of view, the exploration campaign will also show if industry can operate without damaging a region of spruce trees, moss, berry bushes and medicinal herbs that supports wildlife ranging from dozens of fish species to gentle hares and beaver as well as fierce predators including grizzly bears and wolves.

In a wider Canadian economic perspective, the Sahtu permits confirm that northern communities learned a lesson from the ordeal that they inflicted on the Mackenzie Gas Project. Despite prolonged preliminary planning and consultations, plus agreement on native part-ownership, formal regulatory review by multiple agencies dragged on for six years in 2004-2010. The exercise delayed the C$16-billion pipeline and production scheme until southern shale development rendered northern natural gas uneconomic.

In Yellowknife last week, Natural Resources Minister Joe Oliver described the lesson during a speech to the annual conference of Canada’s federal and provincial energy and mines ministers.

In the energy industry growth opportunities are “perishable,” said Oliver. “Where development is deferred, communities suffer from loss of opportunity,” he warned in a statement aimed explicitly at Aboriginal societies that control vast tracts of northern Canada under land claims settlements. “The Mackenzie Gas Project represented a tremendous opportunity for Aboriginal partners. But the regulatory review took almost a decade to complete. By the time it was done, the opportunity had passed, an irretrievable loss for an entire generation.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |