LNG | LNG Insight | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Benefits of New European Infrastructure Questioned as Outlook for Natural Gas Mixed

Europe would benefit from the controversial $11 billion Nord Stream 2 (NS2) natural gas pipeline and additional gas infrastructure, even though demand is seen declining over the long term, according to IHS Markit.

“It is in the interest of European consumers to have abundant choice of import infrastructure from both price and security of supply considerations — especially if the infrastructure investments and risks are born by private companies,” said IHS Markit’s Michael Stoppard, chief strategist for global gas.

“For example, more infrastructure allows Europe to choose between pipe and LNG supply, whose relative availability changes over time.”

According to IHS Markit, European gas demand, including Turkey, was 524 billion cubic meters (Bcm) in 2019 and is expected to fall to less than 510 Bcm by 2030. A long-term decline in European gas demand is expected after 2030, with the extent of the drop depending on progress in electrification, implementation of renewable power generation and the use of renewables to replace fossil fuel emissions, Stoppard told NGI.

Indigenous European gas production, excluding Norway, also is set to fall, Stoppard said, from 98 Bcm in 2018 to about 76 Bcm by 2030. Forty percent of the decline would come from the UK, 22% from Romania and the rest from other European producers.

The bulk of European imports, meanwhile, are expected to be from LNG and Russian pipeline gas, with North Africa and Azerbaijan supplying a small portion, according to the consultancy.

Stoppard’s comments came soon after the German Institute for Economic Research, aka DIW Berlin, wrote that Europe does not need any more gas infrastructure, despite the German government’s support of NS2 and proposed German LNG import terminals.

“The Paris climate agreement calls into question stable demand for natural gas in the coming decades” in Europe, DIW said.

The think tank, which is funded by the German and Berlin governments as well as contracts with other parties, added that “climate change targets can only be achieved if the whole of Europe becomes climate neutral. This means abandoning fossil fuels such as natural gas. The ‘gas exit’ will make new pipelines even more superfluous.”

Stoppard declined to comment on the study, but said so-called superfluous capacity based on annualized totals “may not be sufficient nor economically optimal” because it may not account for seasonal and daily peaks.

“As more volatile renewable power production grows, there will be an increasing need for daily infrastructure capacity, even as annual load falls,” Stoppard said.

A number of regional European markets need more infrastructure to address bottlenecks that can lead to localized price spikes, Stoppard said. Such areas include connections between France and Spain, the UK and northwestern Continental Europe and central Europe, he said.

Meanwhile, new LNG regasification capacity at certain locations could be a better option than using existing regasification capacity by eliminating the need to build expensive pipelines to connect markets. Since suppliers generally underwrite the cost of new regasification through capacity bookings, the risk would be borne by non-European parties, Stoppard noted.

Franziska Holz, one of the two co-authors of the DIW report, told NGI that the study did not analyze regional European issues, but examined the European Union (EU) as a whole. But DIW still concluded that regional natural gas constraints could be addressed through proposals to significantly increase European production of methane and hydrogen from renewables.

European gas demand at best is expected to remain flat in the mid-term and needs to decline over the coming decades to meet the carbon-reduction goals of the landmark United Nations climate change accord reached in late 2015, better known as the Paris Agreement, said the DIW.

DIW said EU gas demand is currently at 400 Bcm/year. The EU imports about 85% of its gas, with about half those volumes from Russia, slightly less than one-third from non-EU country Norway and about 10% from Algeria. About 85% of gas imports arrive via pipelines and 15% as LNG. Germany consumes about 80-90 Bcm/year, with Russia and Norway by far the major suppliers.

According to a global gas model that DIW helped develop, EU gas consumption could drop by as much as one-third by 2050 with the replacement of gas-fired generation by renewables, Holz said. The other two-thirds of EU gas consumption, equally comprising space heating and petrochemical feedstock, isn’t likely to fall significantly by 2050.

Germany’s decision in July to phase out the use of coal by 2038 could cause the nation’s gas consumption to increase, but it would not help reach the Paris Agreement goal of capping global warming this century at 1.5 degrees C because “natural gas is no more climate-friendly than coal,” according to DIW. Other experts, including the International Gas Union, note that gas emits 65% less carbon dioxide than coal in power generation equivalents.

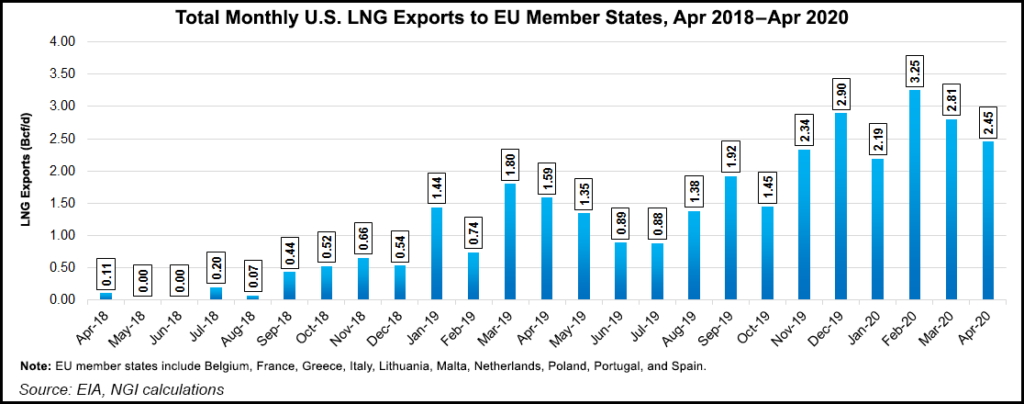

Declining EU gas production could be offset by increased LNG imports from a number of nations and higher North African pipeline gas imports, according to the global gas model. Europe is a key market for U.S. LNG, importing roughly 161 of the 325 American cargoes that have been exported so far this year, according to NGI calculations.

[Want to know how global LNG demand impacts North American fundamentals? To find out, subscribe to LNG Insight.]

But building additional LNG import terminals would “be just as superfluous as building new pipelines” because Europe already has about 165 Bcm/year of LNG regasification capacity, equivalent to more than one-third of the EU’s annual consumption, the report said.

Declining U.S. Imports

Even if all Russian pipeline gas exports to the EU stop, existing European LNG import capacity would be able to handle a potential influx of U.S. LNG to compensate for such a shortage, the report said. DIW’s gas model predicts Europe to import 30% of the U.S. LNG produced this year, but only 20% in 2030, 12% in 2040 and 2% in 2050.

Nevertheless, the 745-mile, 5.3 Bcf/d NS2 pipeline likely would be completed, despite recent threats of U.S. sanctions against participating companies, because there are only 100 miles remaining to the German shore, Holz said. NS2 would run from Russia to Germany through the Baltic Sea.

NS2 spokesperson Irina Vasilyeva has told NGI that the pipeline is needed to help address an expected European gas import gap of up to 120 Bcm/year by the mid-2030s. “The long-term trends of the European market remain unchanged: the EU’s own gas production is expected to halve in the next 15 years,” she said.

NS2 spokesperson Jens Mueller said U.S. efforts to prevent the pipeline’s construction “reflect a clear disregard for the interests of European households and industries, who will pay billions more for gas if this pipeline is not built, and the European Union’s right to determine its own energy future.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |