Opinion | International | LNG | LNG Insight | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Shale Daily

Assessing Spain’s Unique Role in Growing Global Natural Gas Market – Column

Editor’s Note: This column is part of a regular series by industry veteran Brad Hitch for NGI’s LNG Insight dedicated to addressing the complexities of the global natural gas market.

The Spanish market occupies a unique place in the universe of the global natural gas market.

The market is tied to the European Union (EU) through common regulation, but it is stranded by a lack of infrastructure. In a market dominated by LNG exports, Spanish regulations apply the “entry-hub-exit” gas transportation model common in the EU that requires payment to put gas into a system or take it off.

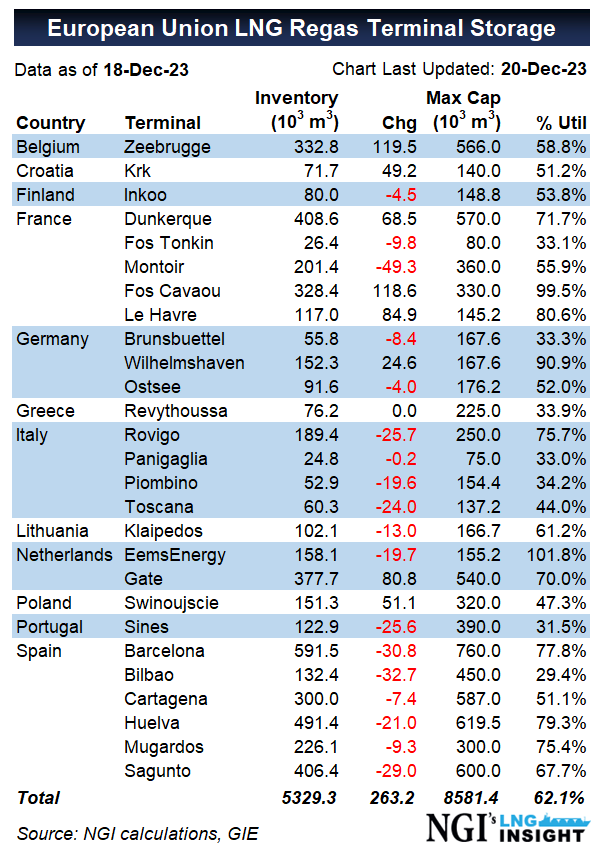

While it is not the biggest individual gas market in Europe, it has by far the largest concentration of liquefied natural gas infrastructure. From the perspective of the U.S. gas market, therefore, Spain is probably best thought about more as an integral part of the Atlantic Basin LNG market than the European gas markets, which have large interconnectivity with the Netherlands and the Title Transfer Facility market.

Late 20th Century Developments

Throughout the history of its gas industry, the Iberian Peninsula has functioned as an island from a market perspective; with limited options in the form of domestic production or European imports it has needed to go further afield for natural gas.

Natural gas consumption in Spain kicked off after the commissioning of the first LNG terminal in 1969. The Enagas SA regasification terminal in Barcelona was originally intended to import LNG from Libyan gas fields operated by an ExxonMobil predecessor – at that time a former partner in what is now Spain’s Naturgy Energy Group SA – but would ultimately serve to import Algerian LNG because of delays in the Libyan project.

Spanish gas imports did not grow rapidly for more than a decade. Although Enagas signed a term contract with Algeria’s Sonatrach under which it was contracted to take 4 million metric tons/year from the early 1970s, it did not come close to meeting its obligations.

The oil shock that spurred other European economies to seek alternatives to petroleum did not create the same reaction in dictator Franciso Franco’s Spain. There was no political drive to create more access to natural gas and demand was slow to pick up outside of the Barcelona municipality.

Energy policy started to take a new direction after democracy was established in the wake of Franco’s death in 1975. Nonetheless, it would not be until the late 1980s that new investments in gas infrastructure helped to spur consumption growth.

Spain’s second and third LNG import terminals were commissioned at Huelva and Cartagena in 1988 and 1999. Natural gas consumption, which had taken seven years to grow from 2 billion cubic meters (Bcm) at the start of the decade to 3 Bcm in 1987, nearly doubled to reach 5.8 Bcm by 1990.

Over the next two decades, Spain went from being a backwater in European natural gas to one of its most dynamic markets. The two new terminals created access to natural gas in the southeast and southwest corners of the country – better enabling the buildout of a nationwide grid.

In the latter part of the 1990s, Spain significantly increased its gas import capacity with the completion of the Maghreb-Europe Gas Pipeline (MEG). The system, which went into service in late 1996 with 8.6 Bcm of capacity, was constructed to export Algerian gas to Spain via Morocco.

In addition to Sonatrach and the Moroccan government, Enagas’ partner list for the project also included Transgas of Portugal. Thus, in addition to creating a direct link to the Hassi R’Mel field in Algeria, the MEG line also inaugurated the first gas imports into Portugal.

With the commissioning of MEG and the inclusion of Portugal, Iberian gas consumption had reached nearly 18 Bcm/year by the turn of the century, three times what it had been at the start of the 1990’s.

Decade of Change

The Spanish gas market continued its rapid growth trajectory during the first decade of the new century, but the implementation of energy policy directives coming from the EU had significantly changed the landscape by 2010.

The regulatory changes being pushed by the EU during the first years of the new century were principally concerned with competition. Although the UK had created gas market competition and established a successful model for trading, the markets outside of the UK were still dominated by large incumbent utilities.

In addition to issuing directives, the EU brought antitrust cases against utilities in larger markets and made asset divestment a condition of certain cross-border mergers. The overarching objective to these regulations was to create open competition within electricity and gas wholesale markets that would lead to liberalization and choice at the retail level.

What set Spain apart from the other countries was that its gas market was still at a relatively new and dynamic stage of development. Whereas the larger markets in Northwest Europe had reached a stage of maturity, it was clear within Spain at the time that there was untapped market potential.

Electricity generation from oil products still represented an unusually large share of the generation mix, for example, and displacement of oil (not to mention coal) presented an obvious opportunity for growth. Spain adopted third-party access requirements for gas and rules forcing electricity companies to sell generation capacity to new entrants, but much of the activity came in the form of new infrastructure development.

Significant gas import capacity was brought online between 2000 and 2010. New regasification terminals were constructed at Bilbao, Sagunto and Mugardos and there were capacity expansions undertaken at Huelva and Barcelona. The overall Iberian market was further built out as well, with the first Portuguese LNG import terminal at Sines commissioned in 2004.

Spain’s second large pipeline project was the Medgaz Pipeline from Algeria. Like MEG, Medgaz was constructed to bring gas from Hassi R’Mel in Algeria to the Iberian Peninsula, only this time deploying a longer subsea Mediterranean section allowing for transit via Morocco to be avoided.

The result of all this development was to allow for Spanish gas consumption to reach 40 Bcm/year by 2008, more than double what it had been in 2000. As anticipated, much of this demand increase had come from new gas-fired electricity generation, with Spain generating 120 TWh of electricity from natural gas in 2008 – a six-fold increase from the 20 TWh of gas-fired electricity in 2000.

The year 2008 has proven to be the highwater mark for Spanish natural gas demand thus far. Gas consumption dropped 10% year-over-year in 2009 as industrial demand was damaged in the wake of the financial crisis. Demand was also impacted by the near doubling in renewable generation within five years, helping to cause gas consumption to drop to 28 Bcm/year by 2014 – a full 30% decline from the 2008 high.

The next column will cover developments within the Iberian market in the years since the financial crisis. Specifically, it will explore how the need to contend with excess capacity in Spain helped to foster innovation in global LNG spot trading, and how some of the recent market developments may impact LNG trading in the years to come.

Brad Hitch has spent more than 23 years working in LNG and natural gas trading from London and Houston. He currently works as an adviser to new market entrants, and he has held senior trading and origination positions at Barclays, Cheniere Energy Inc., Enron Corp., Merrill Lynch and Williams.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |