NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | E&P | LNG | Markets | NGI All News Access

Australia’s Slot as Top LNG Producer Will Be Short-lived, Says Analyst

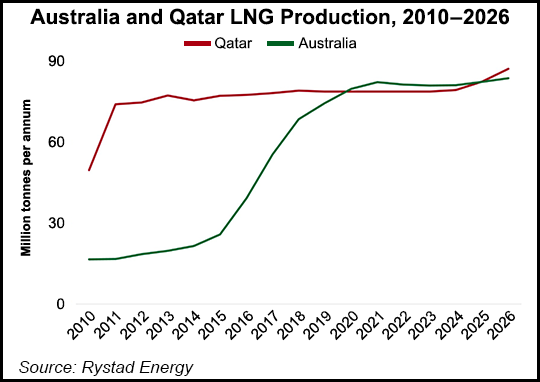

Australia is poised to become the world’s largest producer of liquefied natural gas (LNG) next year and will retain that position until 2024, when Qatar will reclaim the top production spot, according to independent energy research and consulting firm Rystad Energy.

“Australia has no intention of relinquishing its hard-earned LNG crown without a fight. Over the next two years, pending approvals on up to seven Australian integrated LNG projects could challenge Qatar as the country with the largest sanctioned LNG volumes from integrated projects during that period,” said Readul Islam, research analyst on Rystad Energy’s upstream team.

Those Australian LNG projects will supply just over 30 million metric tons/year (mmty) at full capacity at a total cost of almost $31 billion from final investment decision to the first export.

Australia temporarily took the top LNG production slot for the first time in November, when it loaded 6.5 metric tons (mt) of LNG for exports, while Qatar exported 6.2 mt. The drop in Qatari LNG exports in November was due to maintenance, making Australia’s time at the top limited.

In 2018, Qatar exported a world-leading 78.7 mt of LNG, a 24.9% market share, while Australia exported 68.6 mt (21.7% market share). Malaysia held the third slot at 24.5 mt (7.7%), followed by the U.S. at 21.1 mt (6.7%). Nigeria held the fifth slot at 20.5 mt (6.5%), while Russia exported 18.9 mt (6%), followed by Indonesia with 15.2 mt (4.8%), according to the International Gas Union’s 2019 World LNG Report. Trinidad, Algeria, and Oman rounded out the top ten list.

Australia, at just over 80 mmty, recently passed Qatar to become the top global LNG leader in terms of liquefaction capacity. Qatar, which was the world’s LNG liquefaction leader for decades, has a capacity of 77 mmty. Moreover, in March the 3.6 mmty Shell-operated Preludefloating liquefied natural gas (FLNG) project, in the Browse Basin off the northwest coast of Western Australia, shipped it first condensate cargo, cementing Australia’s liquefaction capacity at the top slot. Prelude is the world’s largest FLNG platform and the largest offshore floating facility ever built.

Further onshore and offshore projects are also being considered in Australia. However, Rystad said that much of the country’s near-term capacity additions are backfill projects intended to maximize capacity utilization at existing hubs. “Most of the imminent LNG capacity additions that are expected in Australia won’t require the construction of additional trains — only the Scarborough development will require an expansion train at Woodside’s Pluto LNG project,” Rystad said.

Qatar has already indicated that it will fight to reclaim its top LNG liquefaction spot. In mid-2017, the gas-rich kingdom surprised energy markets when it announced that it would increase its liquefaction capacity from 77 mmty to 100 mmty within five to six years by increasing gas production from its prolific North Field, as well as building more LNG infrastructure and three new liquefaction trains. Last September, Qatar raisedthat number again, stating that it would add a fourth liquefaction train to bring it’s projected capacity to a record-breaking 110 mmty.

A liquefaction capacity of 110 mmty would likely put Qatar ahead of its top competitors, including Australia, the U.S. and Russia, which is also pushing through with a number of new capex-intensive LNG export projects. The United States is expected to become the third largest LNG producer by the end of the year, according to a recent U.S. Energy Information Administration report. U.S.export capacity is expected to reach 8.9 Bcf/d by the end of 2019.

Charlie Riedl, executive director of the Center for LNG, said in January that the U.S. LNG industry was primed for remarkable growth this year, with multiple projects coming online to nearly double exports to the growing global market. “Because of our massive natural gas resource base, the United States is in a unique position to provide natural gas to eager partners across the globe,” Riedl said.

Despite continued growth, headwinds remain for the world’s top-three LNG producers. Qatar is still facing a Saudi-led political and economic boycott put in place in November 2017 over allegations of supporting and funding terrorism, as well as claims that Doha has pivoted politically toward Saudi-regional rival Iran. Doha vehemently denies those claims. Also participating in the boycott are the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt.

Though Qatar has managed to make a comeback since the boycott was initiated, it can still create systemic economic problems for the country. It’s also likely that Qatar decided to increase its liquefaction capacity at least in part to offset the impact of the boycott. Both Saudi Arabia and Qatar have recently invested in U.S. LNG projects to help diversify their collective global energy holdings.

Australia has different hurdles to overcome. The country now exports so much LNG that it could face a natural gas shortage on its eastern coast beginning in 2024 unless new reserves are developed and new pipeline capacity built, the Australian Energy Market Operator warned recently. The world’s upcoming top LNG exporter has as many as five new LNG import/export terminal proposals under consideration to help offset any potential domestic gas shortage — a development unimaginable just a few years ago. In April, the New South Wales government approved a new A$250 FLNG terminal atPort Kembla, south of Sydney.

The U.S. LNG sector has mostly geopolitical problems standing in its way. Amid the ongoing trade war between the U.S. and China, Beijing recently increased tariffs on U.S. LNG from 10% to an imposing 25%, effectively putting the brakes on U.S. LNG exports to China. However, trading houses and secondary sellers will likely still procure U.S. LNG to sell to China.

The quandary for the U.S. is that many of its LNG export project proposals need to sign long-term off-take agreements with Chinese firms to help fund their projects and reach the all-important final investment decision to go forward.

Without both long-term supply deals with Chinese firms and possible funding from Chinese financial institutions, many proposals not backed by cash-laden oil and gas majors will never materialize, thereby thwarting a second wave of U.S. LNG development. The loss of Chinese funding could diminish the country’s chance to vie for the world’s second largest liquefaction capacity spot and push Qatar’s 110 mmty capacity out of reach.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |