Markets | LNG | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Weaning Off Dutch NatGas Production Said Costly with LNG Market Oversupplied

Northwest European natural gas markets face massive investments in infrastructure as the region will have to accommodate new supply sources that don’t align with the current output coming from the European Union’s largest soon-to-be-shut gas field, according to Wood Mackenzie.

Output from the Groningen gas field in the Netherlands has been in decline for years and is set to be cut by two-thirds beginning in October 2022 and shut down by 2030. The major supply loss is said to be the nail in the coffin for the Dutch field, which became a net gas importer for the first time in 2018.

The Netherlands consumed an estimated 35 billion cubic meters (Bcm) (1.2 Tcf) last year, “and for the first time the country was a net importer,” said Wood Mackenzie’s Hadrien Collineau, senior research analyst for gas/liquefied natural gas (LNG). The country imported an estimated 5 Bcm (176.6 Bcf). “By the time Groningen shuts down, it will be a 25 Bcm (882.9 Bcf) market for imports.”

Securing new supply will be a key challenge for the country as the only options available in the areas are Norway, Russia and LNG, according to Collineau, who spoke during a GasTalk webinar last Thursday. Another challenge is that the current infrastructure in the region was built to accommodate the exclusively low-calorie gas coming from Groningen.

“This will require major investments not just in the Netherlands, but also Belgium, France and Germany,” Collineau said. “In the meantime, quality conversion is being used and is possible, but eventually all of the infrastructure in Northwest Europe will have to work with high-cal gas.”

The need for new gas supply comes just as the global LNG market is becoming oversupplied as increased capacity, particularly in Australia and the United States, has hit the market at a time when demand has softened. Collineau said there was a time when the question was whether demand would keep up with all the new supply. “Until 2018, the answer was yes.”

That’s because LNG demand in China rose more quickly in 2018 than supply. “Demand increased so quick that people thought the glut wasn’t going to happen,” Collineau said.

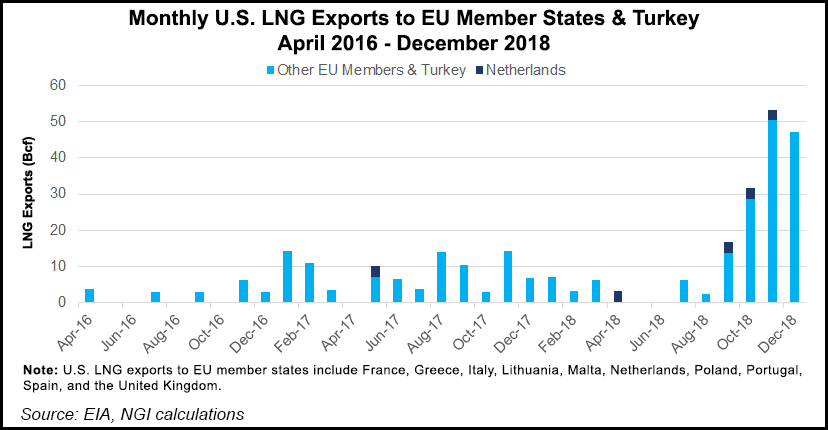

A shift began to occur in October as a mild winter, supply additions and better management of seasonal imports into China led to an oversupply situation that allowed for more LNG in other markets like Europe. “Imports were up 60% in 4Q2018. These levels of high LNG imports have continued into January and February,” Collineau said.

Like many other government and private experts, Wood Mackenzie expects the current oversupply situation to continue through 2020, at which point demand will gradually catch up. During the nearly two-year window before then, however, the question remains of how the major European suppliers will respond to the additional inflows of LNG, particularly Russia.

“If they want to maintain exports at current levels, prices would need to drop much lower,” Collineau said. “This creates some downside risk to Europe and gas forward prices, especially this summer.”

Earlier this month, the 28 member nations of the European Union demonstrated their commitment to an agreement reached last July with the United States to import more LNG and build more terminals. The European Commission reported last Friday that the EU has increased U.S. LNG imports by 181% to 7.9 Bcm (279 Bcf) since the agreement was announced.

EU imports of U.S. LNG were 1.3 Bcm (45.9 Bcf) in January, up from 102 million cubic meters (3.6 Bcf) in January 2018. In February 2019, total U.S. LNG imports amounted to 0.6 Bcm (21.2 Bcf), according to the Commission.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |