LNG | International | LNG Insight | Natural Gas Prices | NGI All News Access | Oil | Opinion | Shale Daily

Column: Back to the Future with Oil in Search of a Global LNG Price Index

Editor’s Note: This column is part of a regular series by industry veteran Brad Hitch for NGI’s LNG Insight dedicated to addressing the complexities of the global natural gas market.

Experienced commodity professionals, upon encountering the LNG market for the first time, will often note the lack of a globally recognized liquefied natural gas price benchmark.

This is not to say that LNG professionals haven’t noticed, as the usefulness of having one has been debated in commercial discussions and from conference podiums for decades.

This column, focused on the potential for oil price indexation to play that role, will be the first in a three-part series addressing the topic. The next article will cover the use of European and U.S. natural gas indexes, and the final installment will examine prospects for the development of an LNG-specific index in today’s market.

LNG transportation was first commercialized in the Atlantic Basin, but much of its early development took place in Asia far away from gas-on-gas competition. In the early days, moving LNG on the water was not cost competitive with gas delivered by pipeline. It was a mechanism for bringing stranded gas reserves in the Middle East and Africa to underserved countries in Asia and Southern Europe.

LNG sales contracts needed to overcome two monumental challenges posed by LNG projects in the early days.

LNG transportation chains (liquefaction, shipping and regasification facilities) were extremely expensive and required long payback periods.

There was no liquid spot market for LNG and few options to replace either a defaulting buyer or seller; everything from upstream well completion to utility pipelines had to be underwritten by the same contract.

Oil-indexed price formulas became part of the solution and were a pragmatic way to accommodate both buyer and seller. Producers were able to value otherwise stranded gas reserves on something approaching an oil equivalent basis. Utility buyers were paying for gas imports at a price that was competitive with other heating and power generation fuels.

Pricing conventions differed between Asia and Europe, with European price formulas typically referencing market prices for refined products and Asian formulas referencing crude oil import prices collected by Japan’s government.

In addition to oil price formulas, LNG contracts were also notable for the heavy use of restrictive clauses and security features.

Producers would often need to overcommit reserves and deliver certificates covering decades of production at the outset. Purchases were committed on a “take or pay” basis with limited flexibility to defer cargoes between years. Cargo movements were restricted by diversion clauses, and LNG tanker loan covenants often prohibited the use of tankers outside of their dedicated routes without bank permission.

The motivation was to make the value chain financeable. The principal side effect was to isolate LNG value chains and convert them into “pipelines on water.” The cumulative effect was to create an industry structure that has been very difficult to move on from.

The Spot Market Genie

Tying LNG import prices to those of crude and refined products enabled utility buyers to pass on costs in line with other fuel imports, but producers could have recovered costs under other formulas.

The commercial contracts formed a closed circuit between buyer and seller and could have been based on a rate of return or cost recovery model. Nonetheless, the use of oil indexation became linked in the minds of many with the need to recover large capital costs, which in turn created resistance to using other mechanisms.

More critically, the contract restrictions that created “pipelines on water” served to choke off the development of a spot market. This meant that every new project encountered the same liquidity constraints as previous projects and would need to deploy the same security features – thereby perpetuating the conventions.

It was not until the turn of the century, when LNG started to engage with wholesale markets in the United States and Europe, that cracks began forming in the status quo.

Where do we stand today?

Not too long ago it seemed that oil price indexation in LNG contracts would follow the same path as oil price indexation in European pipeline gas contracts – coexist for a time with spot markets while giving ground to natural gas spot or wholesale market indexes in term deals.

Extreme price volatility brought on by demand returning after the Covid-19 pandemic – and greatly exacerbated by the conflict in Ukraine – seems to have caused a rethink in some corners. Several long-term contracts that have been signed recently for volumes within Asia and the Middle East are rumored to have been contracted on Brent crude index formulas.

Does this mean that oil indexation will push competing indexes aside and become the de facto LNG benchmark? No.

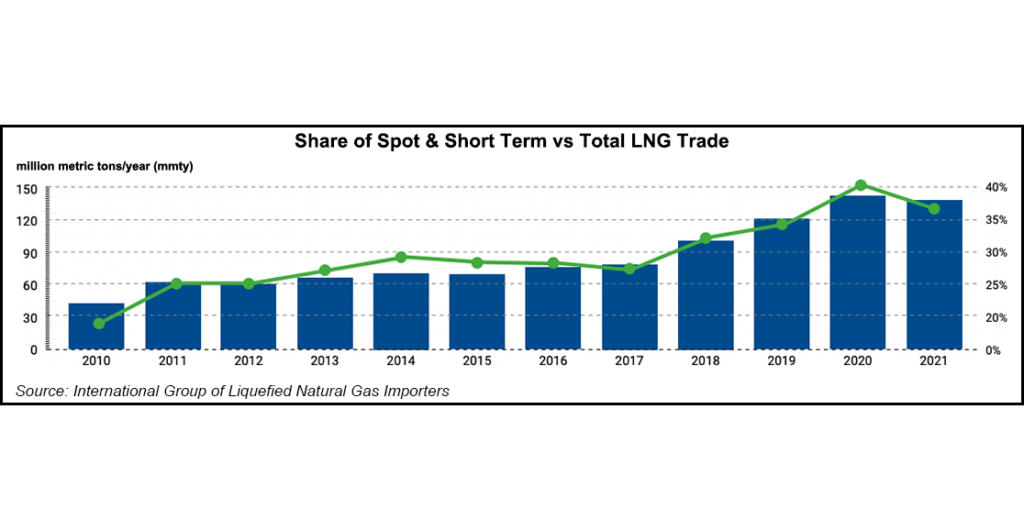

There is an understandable reluctance to embrace LNG or gas spot price indexation in the current environment. Nonetheless, the spot market genie has escaped the bottle and has an important role to play in the global gas market.

The “pipelines on water” commercial model was predicated upon long-term demand forecasting without the need to facilitate dynamic fuel switching. It was also dependent upon Asian utility buyers that made large investments in expensive LNG storage, thereby allowing them to absorb seasonal demand fluctuation.

This is in stark contrast to the modern industry with its multiplicity of floating regasification units tied to weather- and hydrology-dependent demand profiles, and the burgeoning need to fit gas demand around intermittent renewable supply.

No amount of resources will enable the industry to perfectly forecast LNG demand thereby making the spot market a critical relief valve. The resale value of LNG cargoes will reflect market fundamentals in the period in which they are not needed, and this often turns out to be a very different price from a static percentage of Brent. One doesn’t need to look far back in history to see examples where acceptance of this type of cross-index risk turned into catastrophe.

This doesn’t mean that oil indexation will disappear from long-term contracting. It still retains the attractiveness it always had for gas producers and can work for well understood baseload demand. It does, however, suggest that it isn’t a true universal solution going forward.

Brad Hitch has spent more than 23 years working in LNG and natural gas trading from London and Houston. He currently works as an adviser to new market entrants, and he has held senior trading and origination positions at Barclays, Cheniere Energy Inc., Enron Corp., Merrill Lynch and Williams. With experience that includes establishing one of the first LNG trading desks, he has participated in various stages of the global gas market’s evolution. During his time at Merrill Lynch, he worked as head strategist on the European gas desk and led an initiative to enter the LNG trading market. Prior to returning to Houston, he worked for Cheniere in London and was primarily responsible for establishing and managing a derivative trading function. He holds an MBA from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and a BA from the University of Kentucky.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |