Markets | LNG | LNG Insight | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

U.S. (Unsurprisingly) Seen Leading Global Natural Gas Production, LNG Trade to 2040, Says IEA

The global thirst for natural gas in the next two decades is forecast to grow more than four times faster than oil consumption, which is forecast to be concentrated in the transport and petrochemicals sector, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The flagship World Energy Outlook 2019 (WEO-2019) issued on Wednesday expects the United States to lead the charge for natural gas production, with expectations it will add by 2025 nearly 200 billion cubic meters (bcm), or nearly 7.06 Tcf, to global production through shale and tight gas reserves. More than half of the domestic output likely is destined for export as liquefied natural gas (LNG).

The U.S. growth in gas and oil reserves, much of which is destined for overseas markets, is going to “limit the ability of traditional exporters to manage exports,” IEA executive director Fatih Birol said. “Countries whose economies are exclusively reliant on oil and gas reserves are facing serious challenges.”

The WEO-2019 provides projections using three scenarios: Current Policies, which is the baseline of how systems would evolve in governments that make no changes to existing policies; Stated Policies, which incorporates current policy intentions and targets in addition to existing measures; and Sustainable Development, which indicates what needs to be done differently to achieve global climate and other energy policy goals.

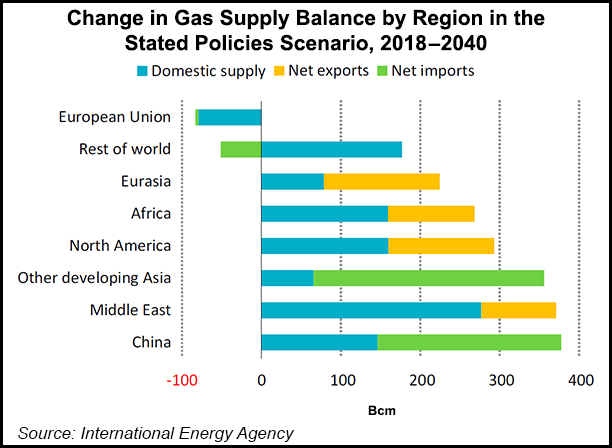

The WEO-2019 projections, entered around the Stated Policies Scenario, said the general consensus forecast expects the United States to produce more gas than the entire Middle East to 2040. Iraq’s output, mostly from associated gas, and Mozambique, with several offshore discoveries likely to lead to LNG exports, also emerge as large producers.

The world is transitioning away from fossil fuels, however, and moving toward more renewables, but it will take many decades before renewables could attempt to replace the use of gas and oil.

“What comes through with crystal clarity in this year’s World Energy Outlook is there is no single or simple solution to transforming global energy systems,” Birol said. “Many technologies and fuels have a part to play across all sectors of the economy. For this to happen, we need strong leadership from policymakers, as governments hold the clearest responsibility to act and have the greatest scope to shape the future.”

LNG, unsurprisingly, is seen dominating the global trade over the coming two decades.

“Technological and financial innovations are making LNG more accessible to a new generation of importers,” the researchers said. “The combination of a growing spot market and more destination flexibility are accelerating a move toward market-based pricing of LNG and away from oil-indexed pricing.”

The share of “pure” oil-indexed import contracts in Asia declines to less than 20% in 2040 from around 80% today, according to the Stated Policies Scenario. However, researchers said there is “significant uncertainty” about the scale and durability of demand for imported LNG in developing markets.

“LNG is a relatively high-cost fuel; investment in liquefaction, transportation and regasification adds a considerable premium to each delivered gas molecule. Competition from other fuels and technologies, whether in the form of coal or renewables, loom large in the backdrop of buyer sentiment and appetite to take volume or price risk.”

Overall gas demand in 2040 is similar to the level projected in the 2018 WEO annual report. However, there is a slight upward revision in the latest analysis regarding the use of gas in industry, which compensates for a downward adjustment in the demand for electricity generation.

Demand in the United States for gas has edged higher, “but this is offset by a sharper decline in the European Union, as well as by slightly slower projected growth in China,” the researchers said. Production growth is dominated by shale/tight gas, “which grows at a rate of almost 4% each year, four times faster than conventional gas.”

The outlook for gas prices was reduced as a “consequence of lower oil prices,” the researchers said. The huge shale/tight gas resources in the United States have put pressure on Henry Hub, which “increasingly influences prices elsewhere.”

Still, the market links between gas and oil are loosening gradually, at least regarding pricing arrangements.

“However, there are upstream ties between the fuels that will be much more difficult to undo,” said researchers. “The outlook for natural gas relies heavily on LNG as a way to connect regional markets and bring gas to new consumers, especially in fast-growing parts of Asia.”

The United States is expected to remain the world’s top gas consumer over the period to 2040, and is forecast to be responsible for around 40% of total global production growth to 2025, initially led by shale/tight resources from the Appalachian and Permian basins.

“The second period, from 2025-40, sees a shift in momentum back toward conventional natural gas, with accelerating production growth in the Middle East and several emerging exporters in sub-Saharan Africa,” according to researchers.

Shale and tight gas production, meanwhile, should become more broad-based as the peak in tight oil production in the United States begins to level off, leading to a subsequent decline in associated gas production.

After 2025, 80% of growth in shale/tight gas is forecast to come from outside the United States, primarily from growth in Canada, Argentina and China, as well as smaller quantities in Australia, Algeria, Saudi Arabia and India.

“Underpinned by ample domestic supply, demand continues to grow strongly until the late-2020s before leveling off at around 950 bcm (33.55 Tcf)” of global demand, researchers said. The scope of large-scale switching in the power sector should then begin to dwindle, “as does the scope for additional gas-intensive industrial development, while efficiency measures and electrification of heat in some parts of the country start to reduce demand in the buildings sector. “

Developing Asian economies are expected to account for one-half of worldwide growth in gas demand, with almost all of the increase from traded volumes.

By 2040, the WEO is forecasting Asian economies to consume one-quarter of global gas output that is mostly sourced from other regions. The average gas molecule also is expected by then to be traveling more than 3,100 miles (5,000 kilometers) to reach consumers in developing Asian markets, nearly twice as far as today.

In part, the massive expansion in China’s gas consumption, which increased by 33% in 2017 and 2018, is the reason for the growth in the global LNG balance, according to the WEO.

China “is underpinning major investments in new liquefaction capacity despite low gas prices in both Europe and Asia. By 2040, China imports almost twice as much LNG as the next largest importing country, India, and the share of gas in China’s energy mix rises from 7% today to 13% by 2040.”

Associated gas from oil production, which reached 850 bcm (30.02 Tcf) worldwide in 2018, accounted for around 20% of the global gas output last year, the WEO noted.

“Globally, only 75% of this gas is used by the industry or brought to market,” said researchers. “We estimate that 140 bcm (4.94 Tcf) was flared and 60 bcm (2.12 Tcf) released into the atmosphere in 2018, more than the annual LNG imports of Japan and China combined. This significant source of emissions represents 40% of the total indirect emissions from global oil supply.”

Meanwhile, compressed natural gas (CNG) and LNG both make inroads in the transport sector to 2040 under the Stated Policies Scenario. CNG primarily is seen gaining ground in the passenger vehicles market, while LNG is entering markets for shipping, as well as trucks and buses.

In other findings, researchers noted that last year, natural gas over its life cycle resulted in 33% fewer carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions on average than coal/unit of heat used in the industry and buildings sectors, as well as 50% fewer emissions than coal/unit of electricity generated.

“Coal-to-gas switching can therefore provide ”quick wins’ for global emissions reductions,” the WEO noted. “Theoretically, up to 1.2 gigatonnes of CO2 could be avoided using existing infrastructure in the power sector. Doing so would bring down global power sector emissions by nearly 10%.”

This year coal prices have averaged around $60-80/metric ton, which could require gas prices below $4.00/MMBtu, researchers said.

“Such prices are below the long-run marginal cost of delivering gas for many of the world’s suppliers, implying the need for additional policy support (in the form of carbon prices or regulatory intervention) to realize these emissions savings.”

In addition, a new market for LNG is on the horizon as more stringent sulfur emissions reductions from shipping are to be required by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) beginning Jan. 1.

“The window of opportunity is relatively narrow and clouded by uncertainty about the lifecycle emissions intensity of LNG,” the WEO noted. “The IMO long-term strategy envisages an overall emissions reduction of at least half by 2050, compared with 2008; in this case, the maximum amount of emissions that could come from ships using LNG in 2050 is estimated to be 290 million metric tons of CO2.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |