Regulatory | Infrastructure | Markets | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

The Energy Wars Part 3: ‘Inflection Point’ Seen for Climate Policy Despite Federal Impasse

Part Three of Three (See Part One; Part Two)

This series analyzes the groundswell of “clean energy” policies being implemented across the country in response to climate change. It examines the implications for the oil and natural gas industry as it confronts society’s growing demands for alternative energy, as well as highlighting some of the viewpoints and technologies shaping the debate at the federal and state levels.

As a debate over climate change and how best to address it intensifies across the country, and as Democratic states move to fill a perceived policy void left by the federal government, it’s become abundantly clear that Congress is at an impasse despite a variety of legislative proposals.

Republicans are more often supporting climate-oriented policies, but the party does not view global warming as a unifying issue like Democrats do. The partisan rift over the matter is growing wider. “The president exacerbates that,” said one energy sector lobbyist. “I think if you had probably any other Republican in the universe as president, there would be a lot more ability to find common ground” on climate issues.

Opportunities for compromise do exist. The oil and gas industry is pushing for clarity on climate issues, led by majors that have called on President Trump to advance carbon pricing. Meanwhile, absent federal leadership, environmental groups are growing more restive and lawmakers across the country are weighing competing proposals for how best to decarbonize. For now, the political moment in the nation’s capitol appears to be setting the stage for a direction on how to combat climate change rather than one trained on building consensus around any one idea.

“I think what’s happening now are the conditions are being set up to create a tipping point, or an inflection point in the not-too-far-off future — in the next decade — with this combination of technology bringing costs down, combined with policy to enable the adoption of that technology and really to force that shift,” said the Boston Consulting Group’s Alex Dewar, who leads the firm’s Center for Energy Impact.

“The politics around the Green New Deal (GND), and the philosophy of mandating outcomes, and not just letting the market sort it out, all of these conditions are starting to form in a way that you see that tipping point coming.”

The GND was introduced earlier this year by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and Sen. Edward J. Markey (D-MA). Even if Congress were to approve the document, and at this point passage is improbable, it’s a nonbinding resolution and would not become law. The measure has since been employed by both parties as a messaging tool more than anything else.

The Republican-controlled Senate rejected the GND in a symbolic vote, while the Democratic-controlled House has yet to bring it up for one, despite 100 Democrats signing on as co-sponsors. The party is divided about the GND’s merits, concerned about its lack of details, its feasibility and how its controversial aspects are likely to play in some districts with another election cycle ahead in 2020.

The GND has, however, sparked additional debate about climate change. In a way, the resolution’s introduction marked the official opening of a war of sorts against the oil and gas industry, which has increasingly been demonized in the fight against global warming as coal’s role in the country diminishes.

The GND “is very aspirational,” said CEO Don Santa of the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America (INGAA) last month. He spoke to reporters at an event in Washington, DC, after INGAA rolled out a study about the role natural gas is likely to play as more renewables enter the power grid. “While it’s been endorsed by some, it’s notable that there are other Congressional Democrats who have expressed less enthusiasm for it. And so I think, if anything, this discussion within Congress is an opportunity for us to educate.”

Essentially, the GND calls on the federal government to create a program that would help the nation meet 100% of its electricity demand with renewable and zero-emission energy sources, overhaul transportation systems, improve energy efficiency and “create millions of good, high-wage jobs in the United States.”

The measure stands in stark contrast to the Trump administration, which has largely rejected climate science. The Environmental Protection Agency recently scrapped the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan in favor of a policy that would support coal and discourage coal-to-gas switching and carbon capture, among other things.

Republican lawmakers, meanwhile, have largely responded with an innovation agenda to push funding that would advance private sector technologies to help curb the environmental impacts of energy production.

Since the GND was introduced, Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-TN) revived his call for a “New Manhattan Project” for clean energy, which would provide more funding from the Department of Energy (DOE) for investments in carbon capture and storage, as well as advanced nuclear research. Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME) introduced a bill to bolster energy storage technology that would also make DOE funding available to enhance battery technologies. Sen. John Barrasso (R-WY) joined Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) to reintroduce a bill that would support carbon utilization and direct air capture research.

“Congress needs to help make American energy as clean as we can, as fast as we can, without raising costs on consumers,” Barrasso said in February when his bill was reintroduced. “…This bill supports groundbreaking innovation to address climate change.”

Clearview Energy Partners LLC said such bills provide bipartisan upside with innovation spending for “climate conscious Republicans and a politically safe climate win for Democrats.” The firm also noted that while Republicans continue to address climate concerns by prescribing “innovation in place of market-based mechanisms” such as carbon pricing, funding bills aren’t likely to pass given the ongoing budget conflicts on Capitol Hill.

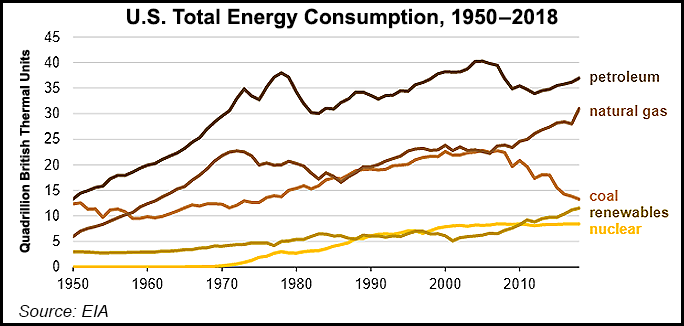

For the oil and gas industry the stakes are high, especially as renewables, energy efficiency and climate-driven state policies are expected to dent demand in the coming decades. Fossil fuels have fallen out of favor in more than a dozen states across the country. State lawmakers are promoting cleaner energy sources in a shift from roughly a decade ago when natural gas was widely viewed as a bridge fuel and an environmental benefit.

“Really the one policy initiative that would have needed to be put into place that would have cemented natural gas as a climate solution would have been some kind of carbon tax or cap-and-trade program,” said former Pennsylvania regulator John Hanger, who served as secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection under Gov. Ed Rendell.

Such a policy, Hanger said, which has over the years failed to gain any momentum in Congress, would have helped the industry combat some of the rhetoric it’s facing today. Big oil companies, which have long advocated for carbon pricing, have for years used it in their operations as greenhouse gas emissions are regulated in some regions of the world already.

The oil and gas industry is also hearing from its own executives, who are acknowledging more often that energy policy is shifting in a way that could negatively impact it in the future if companies are unwilling to come to the table and adapt.

“We have to be part of the dialogue, we have to be part of the solution,” said Dominion Energy Inc.’s Donald Raikes, senior vice president of gas transmission operations. “We are the primary target now of a very sophisticated, well-funded machine,” he said of environmental groups. Raikes recently addressed a crowd gathered in Pittsburgh for an industry conference, telling attendees they can ill-afford to sit on the sidelines as “climate deniers.”

The Environmental Defense Fund’s Mark Brownstein, senior vice president of energy, said a carbon tax could still be one of the best options for the United States to curb climate impacts and one that likely has “the greatest opportunity for consensus between environmentalists and industry.”

Proponents argue that a carbon tax or cap-and-trade program would create a climate of investment certainty for natural gas operators that would also send a clear signal to the market about what’s most valuable. It might also stimulate the private sector to refocus attention on meeting demand for zero-carbon energy going forward and assauge a growing segment of the public concerned about global warming.

“I think ”keep it in the ground’ is a manifestation of people’s frustration with the lack of progress on getting meaningful climate policy enacted federally,” Brownstein said. State policy making might be effective in the near-term, but ultimately “federal leadership” will be needed to address the enormity of global warming.

Both climate change and energy are shaping up to play a role in the next presidential election in a way that hasn’t been seen in recent cycles.

“Our focus now is on making sure we build a political coalition in this country such that no one ever gets elected president of the United States again who isn’t 100% committed to the issue of climate,” said Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT). He spoke with reporters in May to mark the Trump administration’s decision two years ago to withdraw from the global climate accord reached in late 2015, aka the Paris Agreement.

All of the Democratic primary candidates for president have acknowledged that climate change must be addressed by the next administration. More than half of the 24 candidates running for the nomination have endorsed either a hydraulic fracturing ban, fossil fuel export ban or eliminating oil and gas development on public lands, according to a recent review of their positions conducted by the Washington Post.

“The midterm elections included climate change being an important debating issue, and it will come up again in the next round of elections,” said Ceres CEO Mindy Lubber. The nonprofit works with investors and companies on sustainability issues.

In the meantime, she added, the issue is only likely to gain traction.

“I don’t expect a bill to pass in the next two years,” Lubber said of federal legislation. “But I do expect minds to be changed, businesses and investors to be prevailing on lawmakers from all parts of the country and all sides of the political fence to know that” acting on climate change “is an imperative now.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |