Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

The Energy Wars Part 2: California Green Model Pushing Natural Gas to Sidelines

Part Two of Three. (see Part One; Part Three).

This series analyzes the groundswell of “clean energy” policies being implemented across the country in response to climate change. It examines the implications for the oil and natural gas industry as it confronts society’s growing demands for alternative energy, as well as highlighting some of the viewpoints and technologies shaping the debate at the federal and state levels.

As an increasing number of legislatures across the country push to decarbonize and shift away from fossil fuels, they have a roadmap of sorts in California, where natural gas has been pushed into an important but secondary role as the state pursues a complex energy transition.

While other states, such as New York and Washington, have sought out a leading role in climate policy, California has become a global leader. The state’s decarbonization goals include both economy-wide and sector-specific policy targets set forth in executive orders and passed in various bills to reduce emissions and achieve carbon neutrality.

Although the state’s policies have limited the use of fossil fuels in certain sectors, some are cautioning that as many options as possible must be kept open given the complexity of decarbonizing the economy of the nation’s largest state.

“The suggestion that decarbonization is easy is concerning,” said Energy Futures Initiative’s (EFI) Alex Kizer, director of strategic research, who spoke at an event earlier this year at Stanford University. EFI, a research organization founded by former Obama energy secretary Ernest J. Moniz, hosted the event to unveil a nearly 400-page report analyzing the ways California can meet its aggressive low-carbon energy goals.

The report was funded by natural gas, business and labor interests, but they had no voice in its conclusions, the authors said. In an interview with NGI, Kizer said California’s ambitions are the right ones and the state is currently on track to meet its climate goals. Still, he cautioned that “it is going to take a lot of options in order to meet these targets.

“It is going to take a lot of technology options, and natural gas is going to need to continue playing a role in the California economy, definitely through 2030 and then most likely still through mid-century.”

That’s a lesson that might translate well to other states, where Kizer said policymakers should understand that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to decarbonization.

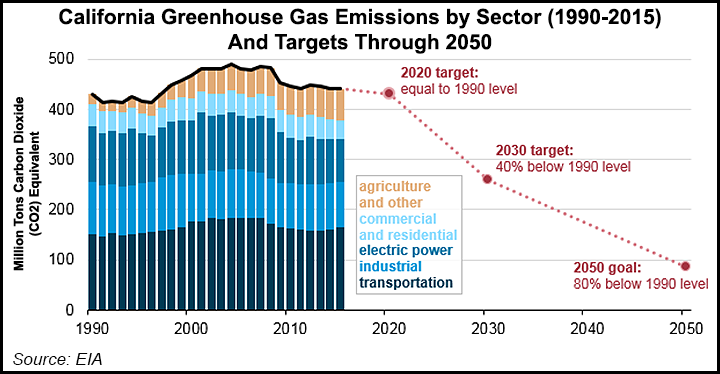

California’s climate targets are some of the most aggressive in the nation. Last year, the state enacted a bill increasing the renewable portfolio standard to 60% by 2030, and it established a 100% alternative energy mandate that requires utilities to procure all their electricity from clean sources by 2045. The state has also committed to reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 80% below 1990 levels by 2050, with an ambitious interim target of 40% below 1990 levels by 2030.

California is among the largest energy consumers in the country and a net importer of electricity, according to the Energy Information Administration. However, even with abundant sun and wind resources, state policies have over the years reduced the role of natural gas.

With large solar arrays and wind farms come intermittent drops in power and cycle frequency. Gas-fired turbines are primarily used to back up renewables. Given that secondary role, there have been few, if any, gas-fired power projects proposed in the state since 2015, and none in the past two years.

The state’s carbon-free power sources accounted for about 53% of the state’s total electricity mix in 2017, including in-state and out-of-state generation sources, versus about 34% that came from natural gas, according to the California Energy Commission.

An earlier target to reduce GHG emissions below 1990 levels by 2020 was reached in 2016, according to a 2018 report from the California Air Resources Board, mainly as a result of increasing renewables. But the power sector is only one aspect of the fight against climate change.

Transportation, manufacturing and agriculture — some of the most difficult sectors to decarbonize — account for about 70% of the state’s emissions. As a result, bills, funding and regulatory efforts have been aimed at advancing electrification, or the strategy of running everything from buildings and vehicles, to appliances and heating systems, on a grid increasingly powered by renewables. The approach is a controversial one depending on whom you ask.

“When you have public policies like ”electrify everything,’ and when regulators, along with environmental advocates, in a very ideological way aim to eliminate natural gas, eliminate gas infrastructure, the unfortunate consequence is you take potential solutions off the table,” said executive director Jon Switalksi of Californians for Balanced Energy Solutions. The group brought together business and labor interests earlier this year to support natural gas and push back against climate change-driven policies for electrifying the state’s energy system.

Reliability and affordability, Switalski told NGI, are being overlooked in the state’s feverish pursuit of a “clean energy” economy. He pointed to Southern California Gas Co.’s 21 million customers, noting that a portion are low-income and receiving discounts on their utility bills. He said if those consumers are forced to use more electricity, their costs could skyrocket. Retrofitting homes or apartments with electric appliances and equipment could also prove costly.

Kizer went further. He stressed that options and innovation must be kept on the table because climate success will have to come across various economic sectors and require multiple technologies for each. Economy-wide targets in particular will present enhanced challenges as they’ll involve sectors not typically considered in conversations about energy, such as agriculture, heavy industry, aviation or the marine sector.

The enormity of the task in any state suggests policies and regulatory reforms are likely to increase going forward to tackle the issues that are being targeted by clean energy advocates, Kizer said. He cautioned, however, that policies affecting natural gas in some sectors, such as building electrification, may have unintended impacts on others that consume and rely on gas, like energy-intensive manufacturing, which has more limited near-term options for decarbonization.

More prescriptive policies, such as California’s goal to put five million zero-emission vehicles on the roads by 2030 might also be served well by other steps. Kizer said the vehicle stock simply won’t turn over in time, noting that the average age of a car in California is about 11-12 years old. It might be a better solution to continue finding ways to make cleaner fuels available for those vehicles, he said.

“When you’re looking longer-term, decades out, it’s really hard to decide today what kind of green energy technologies or policies you should have,” he said. “You need a bigger, wider view” because of everything involved in such a broad policy push.

Given the current state of alternative energy technologies, especially in the power sector, BTU Analytics’ Tony Scott, managing director of analytics, said there’s likely to be a role for gas in the state’s economy for a long time to come.

“Where the challenge comes from is making sure the regulatory frameworks adjust to account for all these things,” he said.

EFI, which has laid out a variety of options in a report for California to meet its near-term and long-term carbon emissions goals, is aiming its research at policymakers, academics, industry and anyone with an interest in energy. Kizer said while his team might take a similar approach to reach their conclusions in other states, the final product would likely be different.

“There are ways to continue the trend toward lowering the emissions footprint of all the states, and I think some policies can work well across the board, but that doesn’t mean that every state should adopt the exact same policies,” Kizer said. “There are unique needs that we found in California that wouldn’t be the case in other states and vice versa.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |