Regulatory | NGI All News Access

Column: In Mexico’s Natural Gas Market, Plenty of Politics, Not Much Policy

Editor’s Note: NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, a leader tracking Mexico natural gas market reform, is offering the following column as part of a regular series on understanding this process, written by Eduardo Prud’homme.

Prud’homme was central to the development of Cenagas, the nation’s natural gas pipeline operator, an entity formed in 2015 as part of the energy reform process. He began his career at national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), worked for 14 years at the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE), rising to be chief economist, and from July 2015 through February served as the ISO Chief Officer for Cenagas, where he oversaw the technical, commercial and economic management of the nascent Natural Gas Integrated System (Sistrangas).

The opinions and positions expressed by Prud’homme do not necessarily reflect the views of NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

It’s been eight months since Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador took office in Mexico, and the energy sector has already seen considerable change. On multiple occasions, the president has stated that he has no intention of changing the constitution to reverse the energy reform of 2013-2014. However, his policy is clearly opposed to the principles that drove that change. Put simply, the reigning energy philosophy has little to do with the ideas of the free market, openness and economic efficiency.

The government thinks that previous administrations weakened state oil company Pemex and state power firm CFE, to the benefit of large global corporations, hastening Mexico’s decline in oil and gas production and weakening its natural gas and power sectors. The drive to develop new infrastructure projects and business models, started in 2014, seems to have reached a turning point. Frequent announcements of upstream rounds, open seasons and tenders, have been replaced by waiting, suspensions, cancellations and contractual commitments challenged in arbitrations.

Although the legal framework is in place, the executive branch has more than enough power to redirect energy policy. What does this mean?

So far, what we have learned is that the government doesn’t want the private sector to compete with Pemex and CFE. Private initiative is fine, but subordinated to what the state wants to implement. Investors are welcome, but only in projects that do not clash with the interests of Pemex and CFE. Successful private operations in this government depend more on successful relationships with the government than on operational performance and attention to the needs of consumers. Meanwhile there is a gradual dismantling of the institutional design that sought to achieve new investment in the energy sector.

The inconsistency between the legal framework and energy policy may well be resolved with a counter-reform. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s Morena party has a majority in Congress, and his popularity would make it possible to reverse the rules of the sector to where we were before 2013, or even before the 1990s.

But this hasn’t happened and the fundamentals remain in place that would make this unlikely. The natural gas industry is an example of this.

Since December 2018, trends in the supply and demand of natural gas have not changed one iota. Mexican production of natural gas continues to drop, despite the Ixachi field coming online, and the shortage of gas in the southeast is increasingly problematic. Gas injected at the Cactus processing plant rarely reaches Coatzacoalcos in the Yucatan. Burgos basin production is falling. Imports are needed to meet this demand.

Meanwhile, Pemex has proposed all sorts of projects to try to get gas to the area, even considering importing wet gas from Texas to process in Burgos. Projects of this nature reveal a reality that can hardly be disguised by ideological speeches. Pemex production continues to fall and visions of a world where this will change rapidly cannot be taken seriously. Even for Pemex, it seems easier to bet on investment in Texas than in Tamaulipas.

At the same time, CFE continues to purchase liquefied natural gas (LNG) in the international market. Although open tenders, invariably it is LNG from North America that ends up discharged at the Altamira and Manzanillo terminals. These intermediation operations are actually profitable to the state company, even as its central purpose is electricity supply. The CFE CEO opposes the company’s incursion into the commercialization of natural gas, but not the positive contributions this activity has on its financial results.

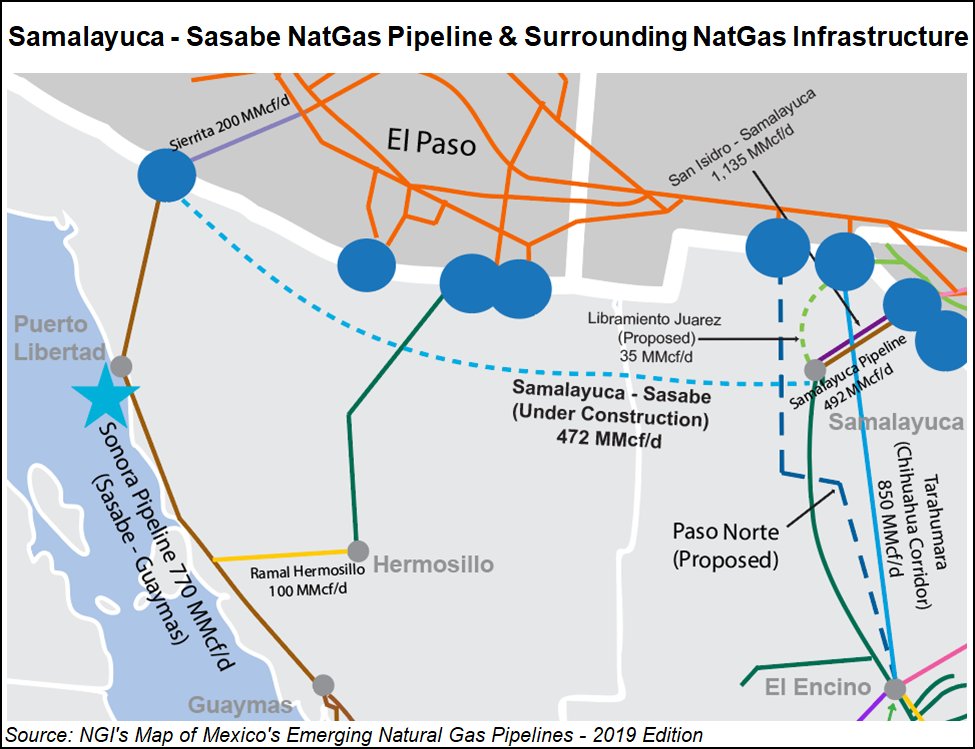

Natural gas demand continues to grow throughout the country. The waiting list of users who want natural gas has not disappeared. This year was meant to see import capacity by pipeline grow from 8.3 Bcf/d to 13.5 Bcf/d, which fueled interest in developing new power generation projects, industrial parks, and even petrochemical projects. Demand growth is estimated at 400 MMcf/d per year over five years.

Pemex’s repeated letters to its users that warn of cuts in the quantities to be delivered under current supply contracts put large gas consumers in a constant search for supply alternatives. With a secondary market for transport capacity, effective open access, new supply routes and interconnections, the entry into operation of Texas-Tuxpan and the Fermaca system that connects Waha with the city of Guadalajara, there should be no problem in getting extra gas.

In theory, natural gas users can solicit any marketer, including Pemex, to present offers with convenient conditions. Pemex’s participation in that market would decrease as players with greater commercial expertise, more efficient prices and more reliable gas deliveries move in. So, put simply, a free market makes the mission of ”making Pemex great again’ a resounding failure.

Under this perspective, it is very tempting to delay the implementation of new aspects of market reform. What we’ve seen so far, based mainly on inaction, seem to suggest that this is the case.

There is widespread suspicion that the independence of pipeline operator Cenagas is at risk. Shipper nominations other than PEMEX are not being confirmed and their programmed volumes are continuously cut. The pretexts for such cuts are operational difficulties. It is noteworthy that when reviewing the data published in the Electronic Bulletin Board, at the time of cuts the volume injected into pipeline system Sistrangas is even greater than what was observed in previous years. A plausible explanation is that a physical restriction did not occur and that the capacity released with the cuts was assigned to other users with upstream capacity. It is not difficult to deduce who or who could be the beneficiaries of the reallocation.

The Hydrocarbons Law places special emphasis on avoiding hoarding. The entry into operation of the aforementioned pipelines undeniably means significant growth in the relationship between the capacity that CFE would have reserved in different transport systems and the peak of its consumption.

CFE should gradually, and massively, release the capacity it has in the Sistrangas and even on new pipelines. The hydrocarbons law includes in its writing the principle of “use it or lose it” to avoid inefficient use of reserved capacity. To date, neither the regulator, CRE, nor the Sistrangas’ operator Cenagas has advanced in the implementation of the secondary market, despite the fact that the Cenagas online system, myQuorum, is in place. It is relatively easy to enable the electronic platform that facilitates the transactions of a secondary capacity market. Eight months would have been enough time for its implementation.

It is difficult to understand, from an energy policy perspective, why the connection between the marine pipeline and the Sistrangas is not yet in commercial operation. The physical interconnection is ready, and the marine pipeline too. But the “Montegrande” injection point is not yet registered in the MyQuorum system, which prevents users other than CFE from using a route that connects South Texas with consumption centers in Sistrangas.

The interconnection between systems is a matter between transport companies and operators. It is not a matter in which an anchor client has power. Cenagas is required by law to contribute to the continuity of services, and to guarantee natural gas supply. CFE is just a client of the marine pipeline, the most important one, but not the exclusive one. The pipeline is a regulated entity and therefore an open access transport route. If the gas does not flow today, it is because of the operator, and this runs contrary to the principle of open access. What’s most disconcerting is that opening this pipeline would greatly alleviate supply strains in the southeast leading to the reduction of costly LNG imports.

The refusal to receive gas seems in line with CFE’s strategy in seeking arbitration, revealing a coordination of efforts between CFE, Pemex and Cenagas. It’s not difficult to see how this could come about. These companies belong to the same shareholder, the state, and all of their directors respond to the same boss.

But Cenagas’ independence is necessary for competition and breaks apart a traditional vertically integrated market. The mandate to generate economic value limits the operation to the threshold where it is no longer efficient and leaves the rest of the market to other players. That principle is valid in a competitive market. Leaving money on the table with inefficient decisions can only be explained by agents seeking to obtain a future income that compensates for the present losses. The increase in supply is not something that worries monopolies. Thus, the costs of the recovery of sovereignty will be set by users.

In the conflict between ideology and fundamentals, there are two possible futures. In both, Texas gas will be the main source to meet Mexican demand for natural gas. To think otherwise would be to bet on a supernatural event.

In the first scenario, CFE and Pemex, with the help of Cenagas, are the unavoidable intermediaries that open and close the gas doors at the border. Agents who entered the market in 2017 during the first open season sponsored by Cenagas will be tolerated but no state company will move a finger to help them. The transition to a competitive market will have to wait another five years for a political window to open.

In the second scenario, the private sector, using market intelligence and taking on some degree of risk, will find solutions that minimize the participation of the Pemex, CFE, and Cenagas triad. This road is complex, but possible in the northern regions of the country and in those that are covered by the Waha-Guadalajara and Sásabe-Mazatlán systems. These regions are already comparatively better off, and the most suspicious of centralism. Paradoxically, a government that seeks to unite the country may end up sharpening economic inequality between the north and south of the country.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |