NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Coronavirus | E&P | Earnings | LNG Insight | NGI All News Access

Shell CEO Says Covid-19 May ‘Capitalize Society’ to Reduce Long-Term Oil, Natural Gas Demand

Royal Dutch Shell plc is buttressing against an uncertain outlook for global oil and natural gas demand this year after profits were decimated in the first quarter by the impact of Covid-19.

The Anglo-Dutch supermajor, a leading natural gas trader and deepwater operator, sliced the dividend by 66% to 16 cents, the first cut to the shareholder prize since the 1940s. The prudent thing for now is to preserve Shell’s long-term health because the duration of the pandemic is unknown, CEO Ben van Beurden said during a conference call Thursday. CFO Jessica Uhl joined him at the mic.

“Considering the risks of a prolonged period of economic uncertainty, including the weaker demand for our products and lower and the less stable commodity prices, we do not consider that maintaining the current level of shareholder distributions is in the best interest of the company and its shareholders,” van Beurden said. The dividend reduction alone is set to free up around $10 billion for the bottom line.

Pressure on the energy industry “has mounted and the threats to economies around the world are real…”

The economic slowdown has cut into liquefied natural gas (LNG) demand, “a material demand drop compared to the projections earlier in the year,” he said. “Similarly, the environment around refining and chemical margins remains challenging,” with oil storage capacity a major issue.

Shell is forecasting significant price and margin volatility in the short and medium term. In addition, the company is seeing “recessionary trends in many of the markets and countries that we operate in, and this volatility presents a unique challenge for oil and gas produced.”

Recovery will come, but as to when is uncertain. For now, the immediate priority is to support the workforce, van Beurden told investors. Ensuring business continuity is second.

Underlying operating costs are coming down by $3-4 billion year/year, with capital expenditures cut to $20 billion, off from initial guidance of $25 billion. Group performance bonuses across the board have been scuttled.

Shell had high expectations as the year began, Uhl said. By the end of March, however, Shell had withdrawn from the proposed Lake Charles LNG export project in Louisiana. In Australia Shell and its partners delayed a final investment decision on a natural gas field project. Sanctioning of a deepwater project in the Gulf of Mexico also has been shelved.

Also taking a hit is the U.S. business overall, where Shell has reduced the rig count. The operator in 4Q2019 had taken a $2.3 billion impairment charge because of the decline in U.S. gas and oil prices.

“We’re effectively pulling all levers that touch our cash sources…to preserve the short term as well as the longevity of our cash flow,” Uhl said. “We need to manage value and risk in the near and long term.”

“Two real big problems” are facing the industry,” van Beurden said. “One is that, of course, everything has become much more challenging macro-wise, and we know it’s going to get worse before it gets better. The biggest challenge we find ourselves is this crisis of uncertainty that we have…It’s not just the oil price, that’s just one aspect. What will happen to demand?”

Demand, he said, “will come down massively…The reduction in demand that has been predicted just for April is going to be 29 million b/d. We don’t know what that may bring. So there’s a lot of challenges coming from that.

“The margins in downstream refining margins, who knows where that will go, who knows actually where the viability of our assets will go in many cases? We have seen people having to shut-in simply because they do not have the logistics inbound or outbound…It is that level of uncertainty that you cannot model scenarios.”

[Want to see more earnings? See the full list of NGI’s 1Q2020 earnings season coverage.]

Shell is working its way through the financial modeling on a day-by-day basis, but it’s not a simple task. The modeling is the “key thing that we have been grappling with and everybody is grappling with, and the only sensible thing to do,” van Beurden said. “In my mind, when these things happen to you, take very decisive action; take the countermeasures that are needed to protect financial resilience because that’s what it will ultimately come down to.”

A few pundits have suggested that the supermajors will be able to swoop in and grab distressed assets as Lower 48 producers and others succumb to low prices. However, merger and acquisition activity “is not a priority for the moment,” Uhl said. “Perhaps this does not necessarily need to be said to everyone. But just the scale and scope of the issues at play that are affecting the company today cannot be overstated.”

Beyond the incredible health issues and the economic implications, “the knock-on effects from a commodity price perspective have been some of the most dramatic impact on the company in recent history,” Uhl said. “That’s affecting us today, and we are uncertain about how that will affect us for the coming years. But we’re expecting more of an ”L’-shaped recovery than certainly a ”V’ or sharp recovery.”

What’s happening, she said, is an “unusual type of dislocation that…is not just while the oil prices are down because we have a supply demand mismatch…Here, we are looking not just at that.

“We are looking at a major demand destruction that we don’t even know will come back,” Uhl said. “So the oil price may come back, but if the volumes are significantly lower, we still have a major dislocation” in Shell’s cash margins.

It’s uncertain whether there may be a “major recession coming” to permanently destroy some oil and gas demand by impacting consumer behavior. “At this stage, the relatively disorderly way in which all systems start to shut down is also going to affect us in ways that are very hard to predict,” Uhl said.

The direction of the pandemic is equally uncertain, said the financial chief. There could be clearer direction by July — or not.

Shell stands ready to “curtail or reduce oil and/or gas production, LNG liquefaction, as well as utilization of refining and chemicals plants,” through June, which could impact sales volumes.

Integrated Gas production in 2Q2020 is expected to be 840,000-890,000 boe/d. LNG liquefaction volumes are forecast at 7.4-8.2 million metric tons.

“More than 90% of the term contracts for LNG sales are oil price-linked,” Uhl noted, “with a price lag of typically three-to-six months.” Upstream production between April and June is expected to be 1.75-2.25 million boe/d.

Refinery utilization in the current quarter is forecast at 60-70%, while Oil Products sales volumes are expected to be 3- 4 million b/d. Chemicals manufacturing plant utilization is forecast at 70-80%, with sales volumes of 3.5-4.1 million metric tons.

Some priorities are not being pushed aside, including a goal to become a net zero emissions energy business by 2050 or sooner. Once the world is on the “other side” of the pandemic, “it is indeed very likely that there will be a few areas that will continue to feel pressure,” van Beurden said.

“We are facing an overhang in the market” likely to pressure oil and gas prices “for some time to come. Of course, those businesses that are sitting behind challenged infrastructure, those businesses that have a high breakeven price…have a very high carbon footprint.” The fossil fuels industry “will be increasingly challenged” because of emissions.

“I think a crisis like this has the potential to capitalize society into a different way of thinking, much as the Paris Agreement has had. So, things like oil could be a challenge,” as well as landlocked operations with high carbon emissions.

“That, by the way, has also very much been the lens through which we have been looking at our portfolio,” van Beurden said. “We have made the choice to get out of high breakeven, high carbon projects…” Across the industry, “I think more of that may still be to come going forward.”

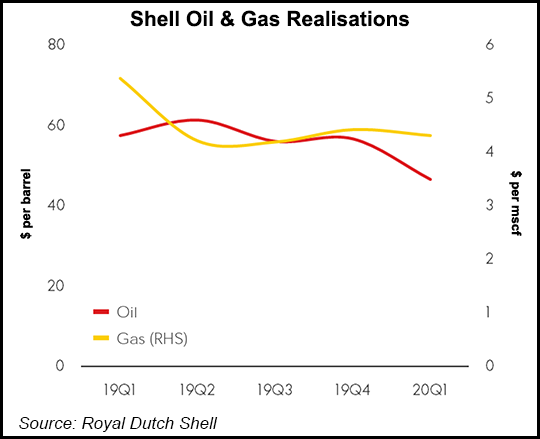

Shell’s current cost of supplies in 1Q2020 fell by 46% year/year to $2.86 billion (35 cents) from $5.30 billion (65 cents). Cash flow from operating activities was $7.4 billion. Revenue plunged to $60 billion from $84 billion.

In the Upstream segment, Shell recorded a $776 million charge on impairments mainly for assets in the United States and Brazil from lower commodity prices. Total production was 5% lower year/year, mainly because of divestments, field decline and lower production in a North American joint venture, partly offset by field ramp-ups in the Permian Basin, Gulf of Mexico and Santos Basin. Excluding the portfolio impacts, production was flat.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |