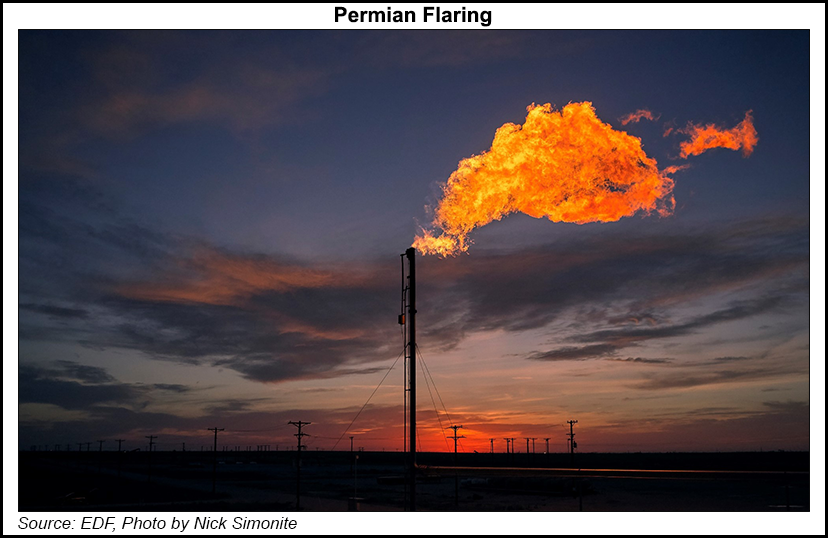

Natural gas flaring from operations in the Permian Basin, Eagle Ford and Bakken shales does not work as efficiently as it could, with as much as 10% routinely unlit or malfunctioning, new research indicates.

The Permian, Eagle Ford and Bakken account for about 80% of the gas flaring in the country, according to the University of Michigan (U-M), which led a collaborative study on the efficacy of gas flaring.

Researchers found that the active flares tracked during the study destroyed about 95% of the methane, not 98% as previously estimated. In some areas, as much as 5% of the flares were unlit, bringing overall efficiency down to about 91%.

“Flaring is widely used by the fossil fuel industry to dispose of natural gas,” researchers said. “Industry and governments...