Mexico | Infrastructure | Markets | NGI All News Access | Regulatory

Mexico Energy Reform Could Spark Legal Controversies, Deloitte Energy Head Says

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |

Natural Gas Prices

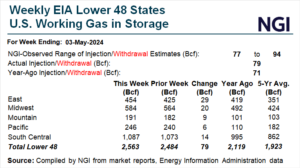

Weekly natural gas cash prices were mixed as continued declines in production and pockets of strong demand empowered bulls, but weakness in West Texas kept bears in that region on the prowl. NGI’s Weekly Spot Gas National Avg. for the May 6-10 period rose 4.0 cents to $1.425/MMBtu. Futures, meanwhile, rallied much of the week.…

May 10, 2024Natural Gas Prices

Natural Gas Prices

By submitting my information, I agree to the Privacy Policy, Terms of Service and to receive offers and promotions from NGI.