Markets | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Argentine Natural Gas Promises Chile Cheaper Energy Prices, Lower Carbon Footprint

As Chile attempts to return to normal after days of protests that have divided the nation, natural gas has emerged as a potential way to help lower the cost of living, which has been at the center of citizens’ demands for change.

Last week Argentine natural gas producers and transporters met Chilean gas buyers and government officials at the 3rd Latin American Energy Summit in Santiago to discuss the Chile opportunity for natural gas from the booming Vaca Muerta deposit in western Argentina.

“The price of Argentine gas in Chile has dropped from $4/MMBtu to $3/MMBtu in one year of exports,” said Tecpetrol’s Leopoldo Macchia, head of oil and gas marketing for the No. 2 producer in Argentina. This compares to liquified natural gas (LNG) import prices in Chile of around $10/MMBtu.

One year ago, the first molecule of Argentine gas for electric power generation in more than a decade was sent across the border via the GasAndes pipeline to Chilean power generator Colbún. The following month, the Gasoducto del PacÃfico SA pipeline was reopened after being shut in 2008 with gas flowing from Vaca Muerta, including from ExxonMobil Corp., to LDC Innergy in Chile’s central-southern BiobÃo region.

Seven pipelines connect the two countries: GasAtacama and NorAndino in the north; GasAndes in the Santiago Metropolitan region; del PacÃfico; and three lines in southern Magallanes.

Macchia said the Vaca Muerta unconventional play is comparable to fields in the United States. Vaca Muerta alone has 308 Tcf of gas, or 110 years-worth of consumption, and Argentina as a nation is second only to the United States in commercial shale gas production.

“We have started developing massively at the FortÃn de Piedra block in Vaca Muerta and the results are comparable if not better than the best Haynesville wells,” Macchia said, referring to the shale play that straddles East Texas and northern Louisiana. “In less than two years, we’ve got to 12% of total national shale gas production at that block alone.”

YPF’s Santiago Romero, general manager for Argentina’s No. 1 gas producer, said there is still tremendous room for growth.

“There is room to keep growing in Argentina and room in Chile to grow. There is also a possibly a chance for vehicular natural gas,” he said. “What we see is that the future is not going to be only regional exports to Chile and Brazil but also global exports through LNG.”

So far, most Argentine gas in Chile is used to generate electricity, principally replacing coal-fired generation in Chile, which has led to “a very important drop” in carbon dioxide emissions, Romero said.

Chile now generates about 40% of its power from coal plants, but it plans to shut all of them by 2040, opening further avenues for natural gas growth. The country currently has 5 GW of installed natural gas power supply, but this along with its pipeline capacity is only being partially used.

AME’s Patricia Palacios, head of unconventional fuels for the generator, said the role of natural gas could be fundamental to improving emissions from Chile’s energy matrix.

“We are in a climate crisis,” she said. “We need to reduce our carbon footprint. We think natural gas has a really big space for growth here. And as a citizen of the south of Chile, our cities’ air is completely dirty and nobody does anything. There is natural gas in Argentina, and it is cheap. All we need is the political will so that it can be a real possibility.”

The head of fuels for Chile at generator Enel, Juan Oliva, said gas “is going to play an important role” in the energy mix in Chile.

“We are completed dedicated to decarbonize as a country,” Oliva said. “Gas is going to be a substitute for coal as we incorporate renewable power. And gas can compete with coal. Our prices are now at $3/MMbtu, which means energy at $35/MWh, very competitive. We’ve been able to introduce gas to our power plants in the center of the country, because Vaca Muerta gas gets there.”

But, he added, right now it “all depends on the performance of Argentina.” Argentina goes to the polls to elect a president at the end of this month, meaning political uncertainty is high for the moment.

The fact is, the history of natural gas trade between the two nations does not have a good track record. Between 1997 and 2004, the neighbors built cross-border pipelines and Chile developed close to 3 GW of gas-fired capacity based on the availability of inexpensive Argentine gas. At the time, gas prices from Argentina were in the order of $1.50-2.00/MMBtu, according to Chilean energy consultancy Systep.

However, a massive economic crisis and a deterioration in the country’s energy sector saw Argentina halt natural gas exports by 2007, and Chile’s gas-fired power plants and its energy system in general were left in a perilous position.

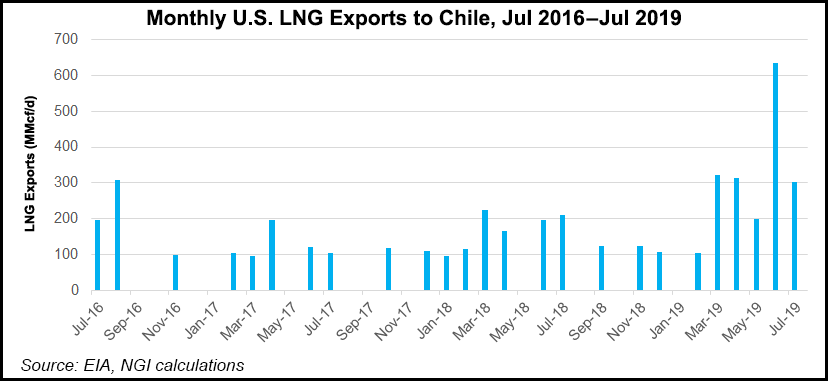

Chile, which must import virtually all of its hydrocarbons, subsequently built two LNG import terminals — GNL Quintero on the coast near Santiago, and GNL Mejillones in the mining-heavy north.

“We are in very early stages of the reintegration,” Oliva said. “The resource is clearly there. We are a small market; about the size of 10% of Argentina’s market. To continue working we need to see the performance of Argentina. We’re going well and welcome Argentine gas; but step by step.”

Methanex Chile CEO Alejandro Larrive said his petrochemical company in southern Magallanes needs supply “that we can rely on always, 365 days a year.” The company has ramped operations since Argentine gas started flowing again last year “and now we are getting back to full capacity,” but long term security of supply is crucial to further growth.

As it stands, gas exports from Argentina to Chile are seasonal, with winter shipments, when demand peaks, not yet guaranteed. Developing infrastructure on the Argentine side, such as additional pipelines and underground storage will be key to this, according to the speakers at the event.

Regulation is also lacking that would help to ease concerns on consistency of supply.

“In Argentina, by law we need to meet local demand first,” said marketing manager Mariano D’Agostino of energy firm Pampa EnergÃa, which owns 60% of Argentina’s natural gas transport capacity through its subsidiaries. “But how you interpret this law is up for debate. Bilaterally, we need to keep working on a protocol for what happens with supply emergencies. Still, in less than one year we are very happy on both sides of the cordillera with the relationship between private companies.”

Innergy’s CEO Nelson Donoso agreed. “I don’t think the relationship between Chilean and Argentine companies has ever been better,” he said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |