Outlook Said ‘Excellent’ For United States-Mexico Natural Gas Exports

The growth prospects for natural gas exports and re-exports from the United States to Mexico over the coming years are strong for multiple reasons, a panel of experts said last Wednesday.

Speaking at the Inter-American Dialogue think tank’s Latin America Energy Conference, David Goldwyn, president of Goldwyn Global Strategies, LLC, said he expects gas demand to continue outpacing supply in Mexico, due to the country’s growing pipeline network and insufficient policies to stimulate domestic production.

Although state oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) plans to invest $1 billion in 2020 to develop the Ixachi onshore gas field, and about $316 million for the gas-rich Chicontepec formation, these efforts, even if successful, will have a “negligible” impact on overall gas supply in the country, Goldwyn said.

On the demand side, he said, the recent commissioning of the 2.6 Bcf/d Sur de Texas-Tuxpan subsea pipeline, the pending completion of the colloquially named “Wahalajara” pipeline system, and the continued expansion by state power utility Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE) of its combined-cycle gas turbine fleet should all lead to growth in U.S. gas imports, which already are at a record high. The 1.2 Bcf/d La Laguna-Aguascalientes stretch of the Wahalajara system is set to come online this month.

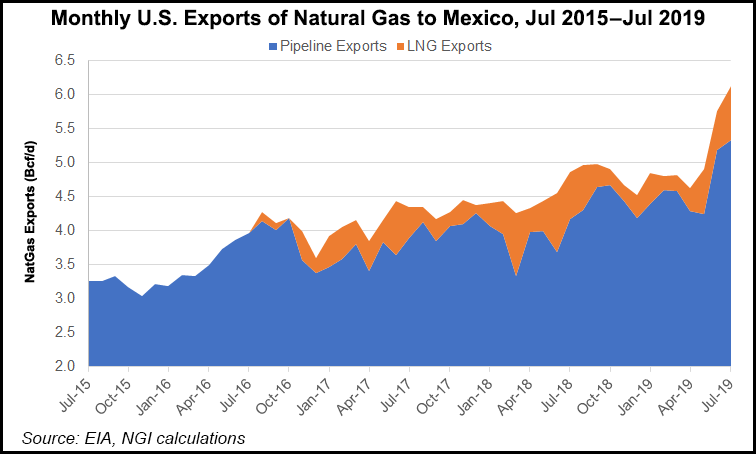

The United States exported 5.3 Bcf/d to Mexico via pipeline in July, up from 4.87 Bcf/d during the same month a year ago, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Exports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Mexico, meanwhile, rose to 784,194 MMcf/d from 685,903 MMcf/d.

Imports accounted for 68% of Mexico’s gas supply in July, up from 67% in July 2018, per data from the Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH).

In August, natural gas marketers in Mexico transacted a record-high 8.07 Bcf/d of natural gas, according to the IPGN monthly natural gas price index published by the Comisión Reguladora de EnergÃa (CRE).

If Mexico wants to reduce its dependency on U.S. gas imports, it should resume bid rounds and public-private joint ventures with Pemex, and invest meaningfully in unconventional exploration and production (E&P), said Goldwyn, who served as the U.S. State Department’s special envoy and coordinator for energy affairs from 2009-2011.

During that time, he conceived and developed the Global Shale Gas Initiative and the Energy Governance and Capacity Initiative.

Goldwyn said it remains unclear whether President Andrés Manuel López Obrador will soften his state-centric energy policies in favor of a more market-based approach.

He expressed concern about the president’s suspension of bid rounds, and his appointment of “unqualified regulators” to replace technocrats at the CRE. Goldwyn added that some regulators were even “personally harassed out of office,” presumably in reference to the departure of former CRE chairman Guillermo GarcÃa Alcocer, a proponent of Mexico’s 2013-2014 energy market liberalization, which López Obrador vehemently opposes.

Speaking on the same panel, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Beth Urbanas, deputy assistant secretary for Asia and the Americas, said she is seeing “excitement” from Asia about the prospects for receiving LNG from the west coast of North America, bypassing the Panama Canal.

She cited two liquefaction projects under development in Mexico’s Baja California state. The developers, Sempra Energy and Mexico Pacific Ltd LLC, expect to reach final investment decisions (FIDs) for their respective projects in 2019 and 2020.

Citing the immense gas-producing potential of Mexico, Argentina and Brazil, Urbanas said the department of energy (DOE) envisions a “hemispheric energy bloc” from Canada to South America that can reliably meet growing LNG demand worldwide.

Analysts at Raymond James & Associates Inc. forecasted that Latin America’s oil production could see a small uptick in 2020 after four years of steep declines driven primarily by collapsing output in Venezuela and Mexico.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |