Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

With AMLO Finally Set to Take Power in Mexico, Energy Sector Braces for Change

After more than a decade of trying, and five months on from a resounding election victory, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) will be sworn into office in Mexico this Saturday, Dec. 1, while turnover of the country’s top energy positions continue.

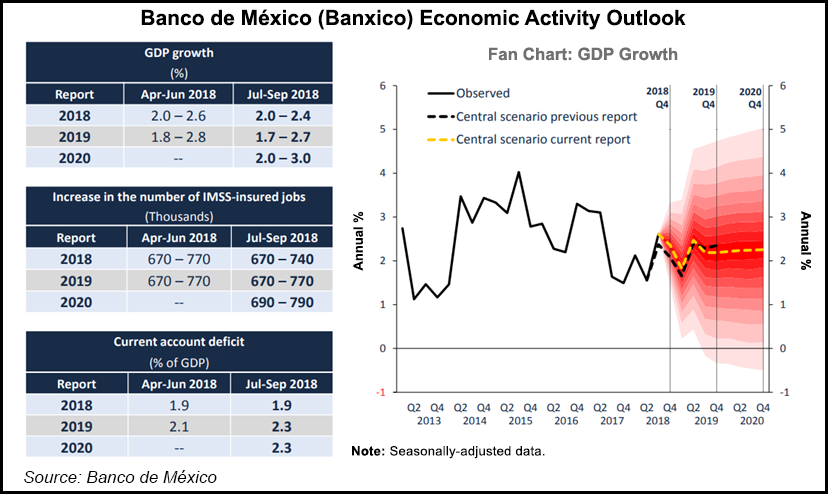

Despite being such a high profile figure in the country, how exactly he will manage the energy sector, and the economy at large, remains in question. Earlier this week, citing uncertainty over the direction of policy under the president-elect, Mexico’s central bank (Banxico) downwardly revised its 2018 and 2019 economic growth forecasts for the country.

In its latest quarterly report, Banxico said it is now projecting 2018 growth in the range of 2.0-2.4%, down from a forecast of 2.0-2.6% in last quarter’s report. For 2019, the range has been reduced to 1.7-2-7% from 1.8-2.8%.

Banxico said that López Obrador’s recent decision to cancel construction of the $13 billion Nuevo Aeropuerto Internacional de la Ciudad de Mexico (NAICM) airport, as well as “the business model of [national oil company] Pemex (Petróleos Mexicanos),” are both driving market unease over Mexico’s investment climate.

The report, which was published on Wednesday, follows López Obrador’s announcement on Monday that his government will proceed with his long-held plan to build a new oil refinery. His pick for energy secretary, RocÃo Nahle, also told local press this week that bid rounds for operating stakes in oil and gas acreage will be suspended until 2021.

One of the general concerns over the past six months has been whether we will see an exodus of experienced energy officials based on AMLO’s criticism of the energy reform. People will also be watching whether his plans to slash government salaries and move federal agencies out of the capital come to fruition.

Earlier this month, one of the bright stars of Mexico’s nascent energy reform, Juan Carlos Zepeda, resigned as president of the upstream regulator, the Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH), with only five months to go before the end of his second five-year term. Zepeda was instrumental in providing transparency and orchestrating the first upstream auctions to be held in Mexico in more than a century.

This week, David Madero was replaced by Elvira Daniel as the head of the Centro Nacional de Control del Gas Natural (Cenagas), which oversees the country’s natural gas network, NGI’s Mexico GPI has learned.

Madero was the first head of Cenagas, and oversaw numerous accomplishments since its creation in 2014, including the first-ever open season for capacity rights on the Sistrangas national pipeline grid in 2017.

Cenagas acts as the technical operator of the Sistrangas pipeline system, which spans 6,256 miles across the Federal District and 20 of Mexico’s 31 states. It also owns and operates the isolated Naco Hermosillo system in Sonora state and administers capacity release auctions for cross-border pipelines on behalf of Pemex and CFE.

Daniel is a lawyer who serves as the legal and communications director for Grupo Danhos, her family’s construction firm. Local press has reported that Daniel is a close associate of Octavio Romero Oropeza, whom López Obrador has tapped to be the next CEO of Pemex.

López Obrador and his transition team have repeatedly expressed disdain for the reforms, and made clear their intention to return the oil sector to the Pemex-centered model that predominated for some 80 years prior to the reform’s passing in 2013.

The refinery news and the postponement of the rounds both corroborate the assessment of multiple analysts that, in order for private sector firms to enter the upstream segment in Mexico under López Obrador, they will have to do so through joint-ventures with Pemex, and on Pemex’s terms.

“I think that what we should expect is a system in which Pemex will come to the center of the field,” the Baker Institute for Public Policy’s Tony Payan said at LDC’s US-Mexico Natural Gas Forum this month in San Antonio, TX, “and the model, instead of being an open field where everybody can participate…will likely be a wheel and spoke system, in which you [can] do business in Mexico, but you will do business with one of the [state-owned] companies, probably Pemex in the case of oil.”

Payan added, “If you put Pemex at the center of the wheel, and you are the spokes coming in, and you have to go through Pemex … then that’s a different model.”

Payan said that Pemex could prove to be a “very tough company” to do business with, “because it is right now quite corrupt.” Payan referred specifically to “the collaboration of Pemex workers with organized crime” in the theft of fuel from Pemex pipelines.

The company reported last week that incidents of fuel theft from its infrastructure rose by 46.5% year-on-year during the first nine months of 2018.

The president-elect’s energy philosophy also centers around a desire to reduce dependence on crude oil imports from the United States through a multibillion-dollar revamp of the local refining segment.

Credit ratings agencies have warned, however, that diverting resources from exploration and production (E&P) to refining could be ruinous for Pemex, which already holds the dubious title of being the world’s most indebted oil company amid a steady decline in the firm’s oil and gas output over the last 15 years.

Banxico highlighted that, between the third week of October and the first week of November this year, Fitch Ratings and HR Ratings both revised their credit rating outlook for Mexican sovereign debt to negative from positive, with the future direction of Pemex under López Obrador figuring prominently in both decisions.

While Moody’s and Standard & Poors have not yet revised their respective outlooks for Mexico, they have warned of the possibility of doing so, Banxico said.

In another sign of markets’ faltering confidence in Mexico, the peso depreciated by 8.4% against the dollar between the third week of October and the end of November, according to the report.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |