Shale Daily | Bakken Shale | E&P | Eagle Ford Shale | NGI All News Access | Permian Basin

U.S. Shale Oil, OPEC Fighting For Market Share, Says Goldman

U.S. shale oil breakevens have fallen by $20/bbl in one year and may decline more on field efficiencies, resulting in a duel with OPEC for market share, while the rest of the industry fights for relevance, according to Goldman Sachs.

In a report published Monday, analysts made the case for the “Top 420” oil and gas projects considered critical to the “new oil order,” which represent 810 billion boe of reserves, or around 87 million boe/d of production by 2025 — 61% of current global production. The projects also represent almost half of the total planned capital expenditures (capex) by the majors over the next four years.

What’s different today is the rising strength of shale oil, propelled by U.S. know-how.

“In our view these projects will not only be the main driver of returns transformation for the producing companies under our coverage, but will also be a key driver” for global oil and gas supplies for the next 10-20 years, as well as merger and acquisition (M&A) activity, and growth/margin transformation for the oilfield services industry.

U.S. onshore operators over the past year helped to reset the breakeven price for domestic shale oil to $60.00/bbl — versus $80 in 2014. Continued efficiency and productivity gains may drive breakevens even lower for longer — up to five years or more, said analysts.

“Over the years, the uptick in U.S. onshore activity has led to greater learning curve effects, resulting in geological improvements and efficiency gains which have unlocked a vast amount of reserves once economically unviable. This clearly offers the industry a degree of choice not available before and therefore a need for greater focus on quality (position on the cost curve) versus quantity (reserves and production).”

The natural gas cost curve also has experienced dramatic changes from 2009, but “this revolution has (at least temporarily) stalled owing to low gas prices in North America and slow development of shale in the rest of the world.”

U.S. shale gas “still looks attractive,” with most fields able to be developed for under $4.00/Mcf. Worldwide, however, the “marginal Top 420 gas fields require $13.00/Mcf-plus,” which means liquefied natural gas projects outside of the United States and “without scale” may not make the cut.

However, the big battle is between U.S. shale oil and the rest of the world. In the United States, that means the Big Three: the Eagle Ford and Bakken shales, and the Permian Basin. The improved economics of domestic shale oil driven by deflation should result in a “more competitive landscape for other pre-sanction developments” around the world.

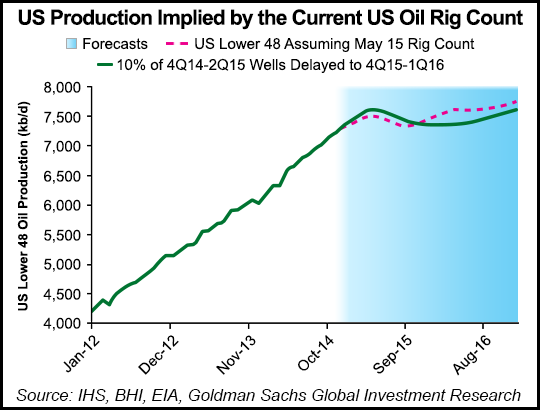

Like other prognosticators, Goldman’s team sees production outside of OPEC member countries slowing in the near term as the impact of lower oil prices and less investments delay projects and cause field declines. However, non-OPEC output should recover in 2017-2018, with stronger growth from U.S. shales and improving decline rates.

“Our current assumptions allow for 500-600,000 b/d of growth from the U.S. shales, which we believe could also ramp up and down as needed to balance the market, thereby providing a further buffer outside of OPEC to cope with supply disruptions or higher demand than we currently expect, albeit at a lag,” analysts said.

Except for some projects, such as the multi-year ultra-deepwater developments, which cost more upfront but produce at higher rates once online, most cost curves “sit above shale and will need costs to come down more in order to compete with U.S. shale,” according to Goldman.

Most of the cost reductions in the domestic onshore are expected from drilling and pressure pumping, with prices for drilling seen falling by nearly 30%, while pressure pumping (fracturing) costs down around 25%. If the Bakken, Eagle Ford and Permian continue to see efficiency improvements, the breakeven price to develop onshore reserves may decline by another $10/bbl to $50/bbl by 2020.

At that price, U.S. shale oil and OPEC alone could meet global oil demand growth to 2025, according to Goldman.

“This could render the Top 420 pre-sanction projects, with $1.3 trillion of associated capex, uneconomic,” analysts said. At $60 oil, 61 of the 420 projects would prove uneconomic post-deflation, which is equivalent to more than $750 billion of capex and 10.5 million b/d of peak production.

What that means in terms of capex is a lot, said analysts. Goldman is forecasting about 30% less to be spent on the Top 420 projects this year and through 2016, versus the 2011-2014 average.

Generally, more M&A is expected in select areas. “Simple value plays” would draw buyers for strategic assets. More acquisitions could happen in U.S. shale acreage by companies that are “sub-scale” in the zones, such as the majors, which today only control about 5% of the total unconventional reserves. More M&A also is forecast for “balance sheet arbitrage,” companies with strong financial capacity able to buy quality assets from struggling owners.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |