NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

U.S. Oilsands? Uinta Project to Test Possibilities

Is the next U.S. energy boom following shale going to evolve around oilsands? A Canadian producer is testing the viability of the unconventional oil based on its work to date in Utah.

A tug-of-war continues between environmental groups and the industry over Canadian oilsands and their entry into the United States via the Keystone XL pipeline. However, the possibility of commercial-scale production from domestic oilsands has begun to emerge in Utah in a portion of the Uinta Basin.

The state recently approved a permit for Alberta-based US Oil Sands Inc. to tap oilsands within the oil and gas basin (see Shale Daily, Jan. 16).

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) last year cut in half the acreage to potentially be made available for oilsands development and restricted it to research and development (R&D) projects (see Shale Daily, Aug. 20, 2012). The restrictions were to apply to Utah, Colorado and Wyoming.

However, with the infrastructure and technology in place, U.S. oilsands could be an another domestic energy source, said US Oil Sands CEO Cameron Todd. His company claims to have successfully field tested a patented process that it developed to make oilsands production more economic with less environmental impact.

Oilsands are found around the world, but the only serious commercial development now being attempted is in Western Canada. U.S. potential might be as big as 2 trillion bbl, while Canada’s potential is “many trillions,” Todd said. However, Canadian reserves are expensive to unlock, compared to what US Oil Sands hopes to do with its project in Utah.

“We’re the only project with this much land that has done field-based pilots to prove that it works,” Todd told NGI. “We’re also the only company with a permitted project, but I fully expect that others will come along with different technologies. It is just that they are several years behind us and they don’t have the same land position.” He said his company has the largest oilsands position in the United States.

With permits in hand, US Oil Sands expects to have the first commercial operation ramped up by next year, with output over the next five years to 20,000 b/d. Todd sees that as only the beginning. He intends to expand in Utah and in Western Canada with a technology that he said requires about 80% less capital investment than the larger-scale technologies now being used.

“We believe that we have a break-through that could have an impact on a very large resource base,” said Todd. He said the technology could have the same impact on oilsands that hydraulic fracturing (fracking) breakthroughs have made in unconventional gas.

“We could change the way surface mining for oilsands is developed. There are billions and billions of potential barrels that are at stake.”

Longer term, the larger development likely will be in Canada, not the United States. “Canada probably has 75 times the resource base, but a lot of it has to be drilled; it can’t be surface mined.”

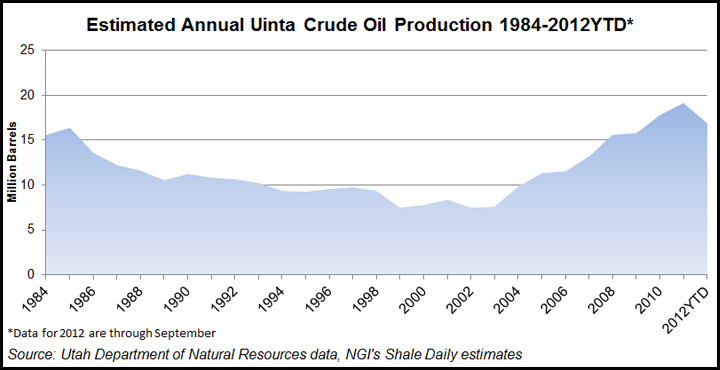

Annual crude oil production out of the Uinta increased steadily from 7.5 million bbl in 2003 to 19.1 million bbl in 2011. Last year 16.9 million bbl came out of the play through September, according to Utah Department of Natural Resources data.

An Alberta-based company, Sunshine Oilsands Ltd., said Thursday it signed a preliminary agreement with Hong Kong-based China Oilfield Services Ltd. (COSL) to have COSL conduct tests in Canada on the use of multiple thermal fluid technologies in oilsands exploration. The technology was developed and patented by COSL.

Extraction is the most capital intensive part, about three-quarters of the overall cost, Todd said. Oilsands production mostly uses classical mining extraction equipment, with processes that filter out solvents from liquids and separate the sand produced. Oilsands ore is basically a sandstone whose pores are filled up with bitumen, or heavy oil.

“So the processes are where a solvent is mixed with the crushed ore, and then the oil, water and the sand, and finally the very fine material, the clay,” Todd said.

US Oil Sands uses biosolvents that are less environmentally harmful and require less natural gas to heat mixtures to desired temperatures compared to the heavier, deeper oilsands processes, he said. It takes just a fraction of the energy that is required in Canada for each barrel of oil.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |