Markets | Infrastructure | LNG | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

U.S. LNG Exports on the Rise, But Limited Infrastructure in Thirsty Global Markets a Big Concern

Note: This is the second in a three-part NGI series titled “Navigating the Nascent LNG Market Through A Choppy World Trade Sea,” which explores the emerging global liquefied natural gas market and the challenges it poses to buyers and sellers seeking to capitalize on the worldwide expansions underway.

For all the economic benefits that liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports are expected to bring to the United States, including bringing an estimated $30 billion back into the domestic economy, a lack of infrastructure to support demand and complex regulatory regimes in some of the fastest growing markets have left industry experts cautiously optimistic about growth potential.

China surpassed South Korea as the second largest importer of LNG in 2017 with imports averaging 5 Bcf/d, exceeded only by Japanese imports of 11 Bcf/d, according to data from IHS Markit and official Chinese government statistics. Imports of LNG by China, driven by government policies designed to reduce air pollution, increased by 1.6 Bcf/d (46%) in 2017, with monthly imports reaching 7.8 Bcf/d in December. An expected surge in 2018 could put China in direct competition with Japan for the No. 1 spot.

The surge in gas demand over the past year led to “severe strains” on China’s gas infrastructure, “as retail and wholesale prices increased sharply and LNG imports ramped up beyond notional capacity limits,” BP plc chief economist Spencer Dale said in a June webcast to discuss BP’s 67th annual Statistical Review of World Energy. The strain also led to widespread gas rationing, with households given priority over industrial use.

“Some of these tensions and strains simply reflect the speed with which gas demand expanded. There’s a limit to how quickly LNG imports can be increased,” Dale said. “Imported pipeline gas didn’t grow by as much as perhaps expected. But the strains also highlighted the underlying weakness of gas infrastructure in China. The network of pipelines across China is incomplete leading to significant distributional issues. Even more important, gas storage capacity in China is inadequate to match the fluctuations in demand.”

Effective gas storage in China is about 3% of consumption, compared to 20% in the United States and Europe, according to BP. “These types of structural issues can’t be fixed overnight and are likely to constrain the extent at which Chinese gas demand outside of the power sector can grow in the near-term,” Dale said.

Japan, meanwhile, increased its LNG imports for the first time in three years, importing 83.63 million metric tons (mmt) in 2017, an increase of 0.4% year/year, according to data by Japan’s Ministry of Finance. Aside from China’s projected demand surge in 2018 that could see imports surpass those in Japan, Japan is likely to remain the top importer of LNG until around 2028, analysts at consultancy Wood Mackenzie have said.

In 2017, Japan’s year/year (y/y) growth was largely due to the sheer amount of nuclear generation that has remained offline following the Fukushima nuclear incident in 2011. Out of more than 40 operable nuclear generation reactors in the country, only four are in service. A cold winter also drove the need for more LNG, with December imports alone increasing 5.4% y/y to 7.95 mmt.

Given Japan’s long history importing LNG, it is ahead of the curve compared to other Asian countries when it comes to having adequate infrastructure in place to support demand. The country has 33 operating import terminals, and pipeline infrastructure is designed to connect to these terminals and nearby markets. The same is true for most Asia Pacific markets, with the exception of Southeast Asia, making an integrated national market virtually impossible.

China, meanwhile, plans to double the amount of natural gas in its primary energy mix to 10% by 2020, according to a directive jointly published by 13 governmental agencies. But aside from LNG import terminals, much of China’s pipeline infrastructure was built for domestic gas or imports from central Asia.

India also has plans of its own to double the share of natural gas in its generation mix to 15% by 2022, but it has only four import terminals. The country would need more than 15 to meet its expected demand, according to Narendra Taneja, a spokesman for the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party.

“China and India have big ambitions to increase the amount of gas they use in their energy mix. But for now, their reach is exceeding their grasps,” an official with an LNG consultancy told NGI.

Indeed, the baton for new LNG demand is being passed from developed to emerging markets in the Asia-Pacific region for several reasons, according to Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. researchers. First, one billion people are expected to urbanize in Asia over the next 20 years, which would drive 65% of world energy demand growth. Second, the energy mix is shifting firmly toward gas and renewables because of chronic pollution across many cities. Third, indigenous gas supply is declining across Southeast Asia, which is creating material deficits in supply to be filled with imports.

“We estimate LNG demand will grow at 6%” compound annual growth rate (CAGR) through to 2030, “which is above most industry estimates of 4-5% CAGR,” Bernstein researchers said. “The LNG market will require over 200 mmt per year (mmty) of new supply through to 2030, or roughly 20-30 mmty in new capacity additions to 2025.

China’s LNG Infrastructure Expanding

China plans to bring online three LNG import terminals this year, increasing the total number of its facilities to 20. State-run China Petrochemical Corp.’s (Sinopec) $2 billion onshore Tianjin terminal in the north received its first cargo in early February from the ConocoPhillips-operated Australia Pacific LNG, Sinopec said. The first phase of Sinopec’s Tianjin LNG project has the capacity to receive 3 mmty, the equivalent of 4 Bcf/d. Sinopec is also pushing forward with a second phase for the Tianjin terminal.

ENN’s $1.5 billion Zhoushan LNG facility, China’s first privately owned import facility, is the second terminal expected to come online in three phases beginning this year with a total planned capacity of 10 mmty. Located on the country’s east side, phase one of the terminal now under construction would be able to receive up to 3 mmty. Phase 2 would increase by 2020 the receiving capacity to 6 mmty.

China National Offshore Oil Corp.’s (CNOOC) Shenzhen Diefu facility in the southern city of Shenzhen in the Pearl River Delta region, rounds out the three import terminals commencing service this year. The facility has a nominal capacity of 4 mmty. CNOOC has eight import terminals in operation, and the Shenzhen Diefu facility would be its ninth. In early June, the company said construction had begun on the first phase of its 10th facility, the Zhangzhou LNG import terminal in Longhai City, near the entrance to the Gulf of Xingu. The first phase would have a receiving capacity of 3 mmty; a planned second phase of the terminal would double the LNG-handling capacity.

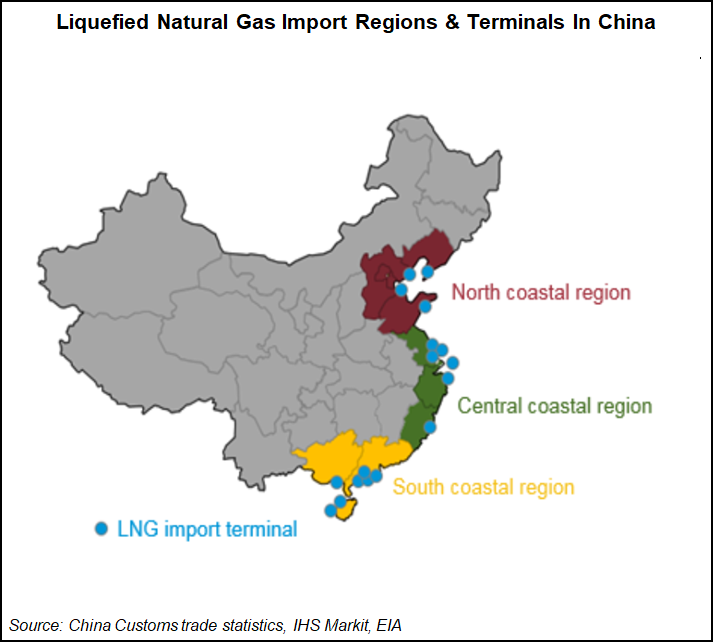

China’s existing LNG import facilities are largely concentrated in its southern provinces, with eight terminals comprised of the Fujian, Yuedong, Dapeng, Dongguan, Zhuhai, Beihai, Hainan and Haikou terminals. Dongguan and Haikou are small-scale facilities. Four LNG import terminals serve the northern part of the country — Dalian, Caofeidian Tangshan, Qingdao and Tianjin, while China’s eastern provinces are served by five LNG import terminals — Rudong, Qidong, Shanghai, Wuhaogou and Ningbo.

China’s three largest LNG suppliers today are Australia, Malaysia and Qatar, while pipeline imports come from central Asia and Myanmar. The United States, with its vast low-cost gas resources, expects to capitalize on the expected surge in Chinese demand by exporting LNG to the country. But infrastructure takes time to build, and China’s dense population has made development even more difficult, sources told NGI.

“A lot of industry is built along the coastline, but those cities are huge and overcrowded. Now, the government is urging facilities to be built more inward. That’s going to mean more new demand along pipelines,” the LNG consultant’s official told NGI.

In the meantime, China has turned to road tankers and tank containers to increase LNG imports. While many of these units distribute shipments from small-scale domestic liquefaction plants, most of them load at the country’s import terminals.

“The problem with that is that you lose some of that LNG very quickly. There’s only so much storage you can build,” said Redwood Markets CEO Ajay Batra, who has nearly 30 years of energy midstream and trading/marketing experience.

This past winter, China still was unable to meet demand even as several of its import terminals operated above nameplate capacity and the country increased its use of LNG trucking. The country ultimately had to allow more coal to be burned than they wanted.

Still, CNOOC plans to go the road tanker route to distribute LNG arriving at its Fangchenggang facility, a small coastal LNG distribution terminal on the Gulf of Tonkin near the Vietnam border that is expected to enter service later this year.

Besides the usual problems of financing and building facilities, the administration of President Trump has created heightened concern that a trade war, mainly with China, but with U.S. allies as well, could unravel the progression of a world LNG market. That possibility will be examined in the third part of this report: “Second-Wave LNG Developers Optimistic About Future Despite Growing Trade Disputes.”

India’s Import Goals ”Aggressive’

In India, the push to more than double its gas use for electricity in the next four years would require imports to increase to more than 70 mmty; the country currently only has about 20 mmty of receiving capacity, Taneja said at an industry conference in February. Plans, however, are in full swing to get three LNG import terminals in service by 2019.

The lack of infrastructure in India is an acknowledged issue among LNG developers in the United States, according to the Center for LNG Executive Director Charles Reidl. “They want aggressive build-outs with aggressive timelines to build that network to shore.”

Indeed, the Adani Group is set to help bring online sometime this year a 5 mmty facility at Mundra on India’s west coast. The terminal, partly owned by Adani, would have receiving, storage and regasification facilities and would be connected to Gujarat State Petronet’s existing pipeline network at Anjaar, Gujarat. Adani also has plans for an import terminal at Dhamra in Odisha. In April, the company said it had signed a long-term agreement with Indian Oil Corp. (IOC) to provide LNG regasification services to the state-run refiner at the Dhamra terminal. Under the agreement, IOC has purchased 3 mmty of regasification capacity for 20 years.

The Dhamra terminal, expected in service during the second half of 2021, is to be expandable up to 10 mmty. The facility is to have two full containment type tanks of 180,000 m3 capacity each and have a jetty capable of handling the largest Q-max fleet from Qatar. The terminal also is to be capable of reloading LNG to service proximate markets via the marine route and be able to accommodate road tankers.

In addition, Atlantic Gulf and Pacific (AG&P) of Manila plans to bring online a 1 mmty import terminal at India’s Karaikal Port by late 2019 and has also executed a supply deal with PPN Power. The project, which could be expanded to 2 mmty, uses a standardized design and modular approach developed in Houston.

The AG&P import facility would complement one being built by Indian Oil Corp. Ltd. at Ennore, 186 miles to the north. More than 90% of construction is completed at the 5 mmty facility, with a “dry run” scheduled for August and full commissioning set for the fall. The project is expandable up to 15 mmty.

Despite the lofty build-out goals, Reidl said U.S. developers are finding some reassurance in the joint task force formed in April made up of a team of U.S. and Indian industry experts. The task force has a mandate to “propose, develop and convey innovative policy recommendations to the Government of India in support of its vision for natural gas in the country’s economy,” according to a joint statement after the inaugural meeting of the India-U.S. Strategic Energy Partnership.

“The fact that you’re seeing engagement from administrations on those issues is a positive sign they’re trying to advance what they’re doing,” Reidl said. “It’s an important one for infrastructure development in india.”

Two of India’s four LNG import terminals in operation are Petronet LNG Ltd.’s 5 mmty Kochi terminal and its Dahej terminal, already a 5 mmty facility with construction underway to expand capacity by another 10 mmty. Ratnagiri Gas and Power operates the 5 mmty Dabhol terminal in the state of Maharashtra, nearly 200 miles from Mumbai.

A Royal Dutch Shell plc subsidiary owns the majority stake in the 5 mmty Hazira import facility and is seeking to double capacity to 10 mmty. In March, the company also announced plans to add a truck loading facility at the Hazira site, noting the growing demand from industrial users with no access to supply from the grid.

Together, these facility imports supply about 6.5% of the country’s energy needs.

Panama Canal Concerns Easing

Aside from the lack of infrastructure in place in fast-growing export markets, the means to transport LNG volumes is also causing some concern that second-wave developers will not be able to get their product to market. The primary route for many Lower 48 LNG exports, largely concentrated along the U.S. Gulf Coast, is the Panama Canal.

But the majority of the Canal’s business comes from container ships carrying consumer goods, not LNG cargoes, according to the Panama Canal Authority (PCA). In early June, the PCA announced that it had set a new monthly tonnage record of 38.1 million tons (PC/UMS) after facilitating the transit of 1,231 vessels in May 2018.

The previous record was established in January 2017, when 1,260 vessels transited 36.1 million tons (PC/UMS) through the waterway, just a month after setting the record with 35.4 million tons (PC/UMS) transited by 1,166 vessels in December 2016. The container ship segment contributed highest tonnage (36%), breaking its segment record with 13.8 million tons (PC/UMS) transited by 229 vessels.

Until recently, only one LNG vessel had passed through the Canal’s waters on a single day, and the Canal still offers only one reservation per day to LNG shippers. However, that’s more than the roughly 5.5 LNG vessels that currently transit the waterway each week, according to PCA’s Jose Ramon Arango, a senior specialist in the liquid bulk segment.

“The Canal offers more than enough capacity to meet the demand for LNG shipments, and remains flexible and in constant coordination with customers around the world to provide safe, efficient and reliable service,” Arango told NGI.

In April, LNG tankers Gaslog Hong Kong, Gaslog Gibraltar and Clean Ocean entered the canal on a staggered basis from the Pacific side. While this was the first time the Canal had transited three LNG vessels through its Neopanamax locks, there have been more than a dozen instances where two ships have crossed the waterway in a 24-hour period day, the PCA said in a statement following the milestone event

PCA, considering the competitiveness of the waterway, completed an expansion in June 2016, Arango said. In designing the third set of locks, it included the possibility of a fourth set of locks should demand from the global maritime industry grow further.

“Whether a fourth set of locks will be considered will depend on in-depth analysis of current and future demand, and we are not able to speculate or assume any specifics regarding a project not yet confirmed,” Arango said. That said, PCA expects to transit as much as 11 mmty in 2018, around 20 mmty in 2019 and 30 mmty by 2020.

Any further expansion of the Canal would likely take time, Redwood Market’s Batra said, noting the multiple delays in getting the 2016 expansion online. “These guys are trying to get a sense of how much business they want to get out of this. Their bread and butter comes from cargoes. LNG isn’t a cash cow yet.”

Meanwhile, the PCA would need to tweak its business model to accommodate the new business coming from LNG. Container vessels attempt to stick to their schedules. “With LNG vessels, there’s a lot more variability. To say this vessel will hit the Canal on this certain date is very difficult,” a global marketing agent for LNG told NGI.

Without an increase in the number of LNG ships allowed to pass daily through the Canal, U.S. exporters would have to seek alternatives to move their product to market. But, other options do not appear as viable.

The obvious destination of choice would be South America, given its proximity to the United States, but countries like Argentina have huge shale reserves of their own. The Vaca Muerta Shale in western Argentina is considered among the most prospective unconventional shale oil and gas plays outside North America. Meanwhile, Brazil isn’t importing as much LNG as it has in the past, and most of its power is sourced by hydroelectric generation.

“The other option is Europe, but they’re a big market for Russian gas. Gazprom has lowered their price significantly in order to protect market share,” the LNG consultancy official told NGI. Meanwhile, Russia also hasn’t given up the idea of expanding its pipeline gas system.

Gazprom has proposed the controversial Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline, which would have 55 bcm (1.94 Tcf) of transport capacity, and would run 1,200 kilometers (745.6 miles) under the Baltic Sea. It would connect the Russian port of Ust-Luga, near St. Petersburg, to Greifswald in northeast Germany. Gazprom expects to enter the pipeline into service in 2019.

Last April, Gazprom signed long-term financing agreements with five European energy companies for 50% of the total cost of the project: France’s Engie SA, Austria’s OMV, Royal Dutch Shell plc and Germany’s Uniper SE and Wintershall Holding GmbH.

The European Union (EU) abandoned its efforts to block Nord Stream 2 in April and began an effort to negotiate with Russia over the pipeline. Poland had led a group of EU countries — mostly in Eastern Europe and the Baltics — in opposition to the pipeline, arguing that it would make them too reliant on Russia for natural gas. Shifting Russian gas deliveries to the new pipeline could also hurt Ukraine, which depends on transit revenue from Gazprom for existing pipelines that traverse Ukraine.

In an effort to reduce its dependence on mainstay supplier Russia, the EU has developed the so-called Southern Gas Corridor. The project includes the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP), South Caucacus Pipeline (SCP) and the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP). Gas pipeline supplies began moving earlier this month from Azerbaiijan to Turkey through TANAP initially from the BP-operated Shah Deniz II field via the SCP. Europe is to begin receiving gas from the system by 2020 via TAP.

In the meantime, industry experts are hopeful that recent discussions between Panama Canal executives and the LNG industry are a step in the right direction. Cheniere Energy Inc. CEO Jack Fusco in May said “the Panama Canal is an important piece of infrastructure for both Cheniere and our customers, and our ability to utilize it efficiently is important, especially as a preferred route to growing demand centers in Asia.”

All three LNG vessels that transited the Canal on April 17 were enroute to Cheniere’s Sabine Pass facility in Cameron Parish, LA, Fusco noted. The company is working with the PCA, which “has demonstrated significant cooperation and support” to increase LNG trade, Fusco said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |