Shale Daily | E&P | NGI All News Access

U.S. E&Ps to Curtail 1.75 Million B/d by Early June as ‘Great Shut-in’ Slams Door on Production

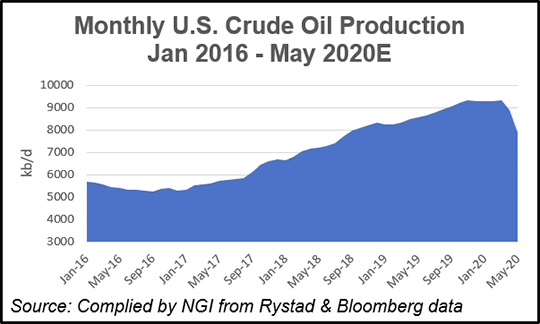

With the Covid-19 pandemic still limiting energy demand, about 1.7 million b/d of existing oil production temporarily could be shut-in across the United States by early June, according to IHS Markit.

Researchers said the curtailments are coming quickly from operating cash losses, lack of demand and storage capacity, as well as “an unwillingness to sell resources at the very low prices” since Covid-19 usurped demand.

“North America has, by far, the greatest number of producers (15,000-plus) and producing wells (more than one million), as well as the greatest diversity of subsurface conditions and operational technologies,” said IHS Markit’s Raoul LeBlanc, vice president of financial services. “This creates immense optionality within the system as companies evaluate and execute the mass shut-ins in response to the market.”

The predicted shut-ins would not be permanent, with most of the oil volumes forecast to come back online through the summer and into the fall “as tightening fundamentals lead operating margins back to positive territory.”

Production also could accelerate if West Texas Intermediate (WTI) oil prices remain above $30/bbl, allowing many exploration and production (E&P) companies to cover their operating costs.

“The oil market fear that characterized March and the extreme price pressure that producers felt in April have galvanized producers across North America into unprecedented action,” said LeBlanc. “Not even the United States’ huge network of storage facilities and associated infrastructure was enough of a buffer for a crisis on this scale.”

Negative oil prices and the collapse of WTI futures contracts “were a potent signal that stronger measures, namely shut-ins, were needed to curb oversupply.”

About one-third of the volumes, or around 550,000 b/d, could remain off the market for the longer term, or until WTI prices “push above $50/bbl,” which then could allow E&Ps to use some of their precious capital to repair wells impacted by prolonged curtailments.

Earlier this month IHS Markit coined the term the “Great Shut-in,” estimating then that curtailed global liquid hydrocarbons between April and June could total up to 17 million b/d, including nearly 14 million b/d of crude.

“The second quarter of 2020 will see the largest volume of liquids production cuts, including shut-in production, in the history of the oil industry,” analysts said, with North America, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and Russia driving most of the cuts.

The consultancy said 2Q2020 oil demand could decline by 22 million b/d versus the same period last year.

U.S. shut-ins are predicted to go beyond stripper wells, which could make up around 350,000 b/d of the overall curtailments. Stripper wells typically produce less than 5 b/d of oil.

Nearly 1.4 million b/d of the curtailments “are expected to come from relatively prolific shale wells,” said researchers. The bulk of the cuts, though, would not be the newer wells, but those “with established production histories.”

Canada also is set to curtail about 500,000 b/d of production, mostly from oilsands projects, “which have a set of options, handicaps and interdependencies that differ from other asset types,” according to IHS Markit.

North America E&Ps share “unique characteristics” that play a role in where and how much to curtail output.

For example, the U.S. onshore “is the only major producing area in the world with primarily private ownership of petroleum mineral rights,” researchers said. “In all other parts of the world, governments own the resource and thus have far greater control of petroleum operations — despite contractual commitments with international operators.”

In addition, 80%-plus of North America’s 36 million boe/d flows into domestic facilities for gathering, processing, refining, purification and to generate power.

“This level of integration means that decisions to shut-in wells have complex downstream consequences across multiple industries.”

Even though the molecules may be integrated, the North American energy sector is disjointed as the industry overall is specialized.

“This has been, by and large, a very successful division of labor, creating a highly efficient and lean chain that is flexible when dealing with routine volatility,” said researchers. “However, ”black swan’ events (such as pandemic-induced economic shutdown) expose the challenges of such lean, optimized systems.”

Another factor setting the United States apart from its global competitors is its abundant storage capacity and ability to relocate oil and gas through the dense pipeline network, according to the IHS team.

“This optionality to store allowed U.S. producers to avoid shut-ins from early March through mid-April, when producers in other countries were already seeing their supply chains seize up.”

The huge network of infrastructure wasn’t enough to buffer for a pandemic-size crisis, but “U.S. producers will have more flexibility as the storage crunch fades.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |