Regulatory | Infrastructure | NGI All News Access

Supply Aggregator Challenging TransCanada-Utilities Pact

A 28-year-old trade alliance is breaking up over TransCanada Corp.’s program for increasing imports of natural gas from the United States into Ontario and Quebec by raising capacity on eastern legs of its Mainline.

Alberta Northeast Gas (ANE) — a Canadian supply procurement agency for 16 New York, New Jersey and New England distribution companies since 1986 — has declared war on the delivery growth plan by TransCanada, Enbridge Gas Distribution Inc., Union Gas Ltd. (Spectra) and Gaz Metro Ltd.

ANE describes the proposal, which was disclosed in a December request for approval by the National Energy Board (NEB) (see Daily GPI, Dec. 30, 2013), as a recipe for toll hikes across the Mainline network from Alberta to Quebec City.

In a protest letter to the board, ANE said TransCanada was wrong to use the word “settlement” as a description of the cooperative construction scheme devised to prevent Enbridge, Union and Gaz Metro from building bypasses around the Mainline.

“The application is not a settlement, but rather reflects an agreement between TransCanada and certain of its stakeholders reached through a process from which ANE was excluded,” said the protest. If approved as submitted to the NEB, the deal between TransCanada and the three biggest Canadian gas distributors spells serious financial pain for others that have long delivery service bookings on the Mainline, ANE said.

“The application seeks extreme short-haul toll increases (greater than 50%) and significant long-haul toll increases (close to 20%),” said the protest, citing cost forecasts provided towards the end of TransCanada’s 94-page filing.

The word used to describe the plan devised by TransCanada, Enbridge, Union and Gaz Metro matters, ANE said.

“By proceeding in this manner [a settlement approval application], TransCanada avoids the board’s two-stage review process and the significant possibility that it will be unable to satisfy the first stage of that process; the threshold question of whether there is doubt as to the correctness of the Board’s decision such that a review is warranted.”

The decision referenced by ANE’s protest was a landmark NEB ruling last year on a hotly contested financial and services “restructuring” proposal for the Mainline.

The case ended in rejection of a TransCanada plan to load costs of excess delivery capacity onto the network’s western half and an order to try refilling it by cutting its benchmark long-haul toll almost in half to C$1.42/gigajoule (GJ) (US$1.34/Mcf) for five years (see Daily GPI, April 1, 2013).

The NEB also rejected a subsequent TransCanada application to set aside and reconsider the decision on the restructuring plan, following a procedure known as “review and variance,” which is the first of the two steps mentioned in ANE’s protest.

ANE urged the NEB to make TransCanada and the Canadian distributors use the longer, more easily contested procedure. Western Canadian gas shippers and the Alberta government were reviewing the settlement application.

As an aggregator of Canadian supplies for northeastern U.S. gas distributors, ANE is still a major shipper with bookings for 555,000 GJ/d (522 MMcf/d) on the Mainline.

ANE’s gas flows through the TransCanada network and then into the United States, mostly on the Iroquois Pipeline from eastern Ontario across New York State and Connecticut to an end point on Long Island.

Both ANE and Iroquois were a growth strategy called the Alberta Northeast Project, which was devised by a coalition of TransCanada, western Canadian producers and local distribution companies serving New York, New Jersey and New England.

The NEB granted long gas export licenses for the plan in 1987 and in 1990 approved C$2.6 billion (US$2.3 billion) in new facilities that enabled TransCanada to fill up Iroquois. The approval rejected prolonged resistance against toll hikes that the pipe and compressor additions loaded onto other Mainline shippers, led by industrial gas users in Ontario and Quebec.

The new growth program devised by TransCanada, Enbridge, Union and Gaz Metro is part of an about-face evolving in the Canada-U.S. gas trade. The plan calls for long-range cooperation on adding facilities for Canadian imports of low-cost U.S. shale production, chiefly from the vast and relatively nearby Marcellus formation in the northeastern United States.

The Canadian import growth program provides for C$391 million (US$352 million) in additions to northbound freeways for U.S. gas during the next three years alone.

Most of the imports currently flow north through border crossings beneath the St. Clair River near Sarnia, ON, and in the Buffalo-Niagara Falls region. As a potential next big step in the trade about-face, Iroquois Pipeline is holding an open season capacity auction this winter to test the market for reversing its flows to deliver Marcellus gas into Canada starting in November 2016, a plan dubbed the South-to-North Project, or SoNo for short.

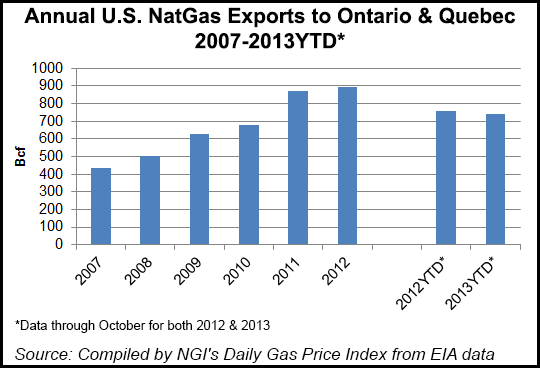

U.S. natural gas exports to Ontario and Quebec have certainly trended higher in recent years, rising from 432 Bcf in 2007 to 891 Bcf in 2012. But the growth of those exports has stalled, with 2012 up only 2.2% year-over-year, and U.S. gas exports to Canada actually down 2.8% year-over-year through the first ten months of 2013.

That growth trajectory could easily resume, however, if continued production in the Marcellus Shale and the emerging Utica Shale creates an excess of local supply. Several industry pundits believe natural gas production in those areas could grow up another 6 Bcf/d by the end of the decade, and that gas would need to find a home. Some of it could be routed south via reversals of existing pipelines, such as Transco has proposed to do, or it could travel west if Rockies Express is able to overcome contractual issues and revert from a west-to-east to an east-to-west line.

Eastern Canada could serve as another taker for the incremental production, assuming that the region fails to advance its own sources of supply, such as the Utica Shale in Quebec, the Frederick Brook and Macasty Shales in New Brunswick, the Horton Bluff Shale in Nova Scotia, and offshore areas like Encana’s Deep Panuke project.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |