Infrastructure | E&P | Markets | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Scientists Say Natural Gas and Storage Essential to Energy Reliability in California

Questioning the state’s narrow vision to rely 100% on alternative energy sources, a report by a nonpartisan group of scientists said natural gas generation and natural gas storage are essential to reliable energy delivery in California.

The California Council of Science and Technology (CCST) concluded that California’s underground natural gas storage risks can be managed as the storage is necessary for wintertime reliability.

The team of scientists also said the state has to do a better job of future energy planning to assess the impacts of moving toward 100% reliance on alternative energy sources.

Even if total conversion were possible, the cost might be prohibitive. “The state should evaluate tradeoffs between the quantified risks of each facility, the cost of mitigating these risks, and the benefits derived from each gas storage facility, as well as the risks, costs and benefits associated with alternatives to gas storage at that facility,” said CCST’s Jane Long, a retired Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory scientist and co-chair of the assessment steering committee.

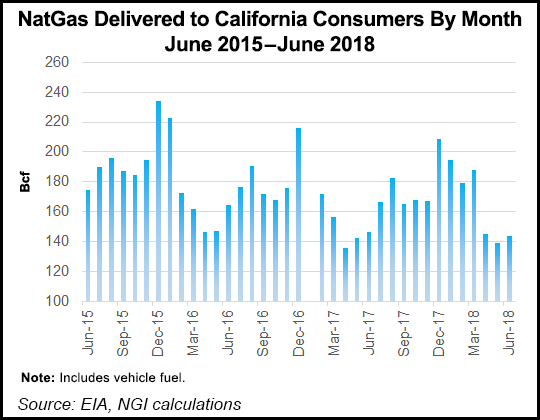

California is one of the nation’s most gas-dependent states, with 6.3 Bcf/d of import capacity and 1.2 Bcf/d of in-state production. The state has 375.5 Bcf of gas storage working capacity , compared to the U.S. total gas storage working capacity of 4.75 Tcf. Southern California Gas Co. (SoCalGas) has 135.4 Bcf of storage capacity and Pacific Gas and Electric Co. has another 100.3 Bcf.

Five CCST-affiliated scientists in late August presented their case at a California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) workshop regarding underground gas storage, as mandated two years ago in the wake of the Aliso Canyon well leak that lasted for four months.

As state leaders push to eliminate the use of fossil fuels, viable, long-term alternatives to gas storage have yet to be identified, according to chief scientist Jeffery Greenblatt of the consulting group Emerging Futures LLC and lead author of the CCST assessment.

“California’s current energy planning does not include adequate feasibility assessments of the possibility of reliable and low carbon future energy system configurations,” Greenblatt said.

The CCST assessment notes that “flexible, non-fossil generation” could minimize reliability issues that currently are taken care of with gas-fired power generation, but there are also “widely varying ideas” about what energy systems might meet the state’s 2050 climate goals. Options include methane, hydrogen or carbon dioxide infrastructure, including underground gas storage.

“California should evaluate the relative feasibility of achieving climate goals with various reliable energy portfolios, and determine from this analysis the likely requirements for any type of underground gas storage in the state,” the assessment said.

The assessment noted that replacing underground gas storage in the next few decades would require large investments to store or supply gas another way, and such new infrastructure, which would bring added costs and risks.

The assessment looked at seven different functions for gas storage, including two financial roles, but concluded the “overarching reason” for underground gas storage was to meet winter demand for gas.

“If storage can meet winter demand, then it can do all the other functions, such as intra-day balancing, compensating for steady production, offering a stockpile against emergencies, and allowing arbitrage and market liquidity,” Long said.

She said a key takeaway on the reliability questions was that “replacing underground gas storage would be very expensive and nearly impossible to do in the near term.”

The technical assessment originally was called for by Gov. Jerry Brown in January 2016 following the storage well gas leak at the SoCalGas Aliso facility, the state’s largest underground storage field. Along with the CPUC and the California Energy Commission, the Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources and the California Air Resources Board completed the report with CCST.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |