Regulatory | Infrastructure | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Regulatory Challenges Mounting for Greenfield Natural Gas Pipelines, Executives Say

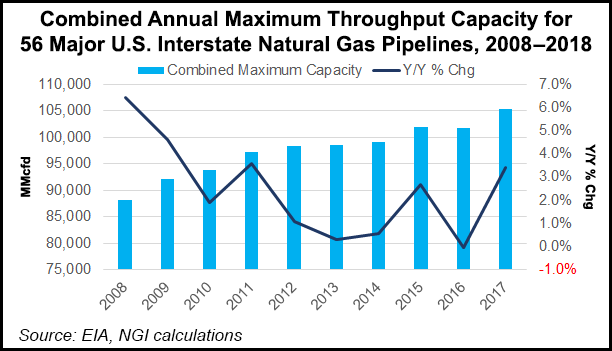

As the regulatory process has become more fraught and politicized for pipeline operators, major challenges lie ahead for the next wave of greenfield takeaway projects that will be needed to tap the full potential of the most active oil and natural gas plays in the U.S. onshore.

That’s according to midstream executives who spoke on a panel at the recent North American Gas Forum hosted by Energy Dialogues LLC. Williams Senior Vice President Chad Zamarin, who was one of the panelists, said Northeast production is forecast to grow to 42 Bcf from 25-27 Bcf/d over the next five years.

“That’s based on projects that are already sanctioned and being constructed,” said Zamarin, who heads up corporate strategic development for the Tulsa-based midstreamer. “The challenge becomes once those projects are complete, that next round of expansion is very expensive and very challenging.”

The pipeline industry is “running out of some of the low-hanging fruit” for expanding capacity out of the Northeast, he said, pointing to projects like Williams’ 1.7 Bcf/d Atlantic Sunrise that capture efficiencies through brownfield expansion.

“We’ve kind of repurposed as much as we can of the existing infrastructure, and so you’ll see a need for much more greenfield construction for the next round of projects,” he said.

It’s a similar story for the constrained Permian Basin as the midstream sector works to keep up with that play’s associated gas output.

“The only way to get that gas to a market that’s really going to be right for it, which is really the Gulf Coast, is through greenfield pipeline. We’ve pretty much maxed out,” Zamarin said. “…It gets a lot more challenging and a lot more expensive. You’ve got to build a 450-mile, 42-inch pipeline out of the Permian every two years for the next 10 years to achieve the takeaway that’s needed for that basin to grow.”

Panelist Sendero Midstream CEO Clay Bretches, whose company operates natural gas gathering and processing in southeastern New Mexico in the Permian’s Delaware sub-basin, called for more efficient federal regulations to streamline pipeline development.

The federal regulations cause Sendero the most delays, leading to some pipelines taking 12-18 months to get in the ground, “which is much too late for us to be able to get our producers to the market,” Bretches said. The lag at the federal level leads to operators seeking workarounds that unduly burden state and private landowners, he said.

“In order to produce our oil and not flare gas, we need the federal government to move faster, and when they don’t, what companies like mine will do is we’ll go and we’ll try to find ways to go onto private land, to state land, some way to move away from the federal government,” Bretches said.

With the New Mexico Permian producers facing more regulatory hurdles compared to their Texas colleagues, Bretches suggested the region’s oil and gas industry would be willing to help fund additional regulators to streamline development.

“We have to have timely approval of rights of way from both the state and federal government,” he said. “What we’re going to need to see, particularly from the federal government, are more regulators in the region…that could be funded in some kind of user tax by the producers to fund more regulators right there in the Bureau of Land Management office in Southeast New Mexico…We’re not asking for less regulation, we’re just asking for timely regulation.”

Meanwhile, as the rise in political opposition to pipeline development has frustrated and stalled beneficial natural gas infrastructure projects, Zamarin counts himself among those calling for the industry to do a better job of telling its story to the public. With activists seizing on the pipeline industry as the most vulnerable part of the natural gas value chain from a regulatory standpoint, Williams has seen almost $2 billion worth infrastructure denied Clean Water Act Section 401 permits “solely for political purposes,” he said.

“We were caught a bit flat-footed as an industry,” Zamarin said. During the downturn a few years ago, industry investment in publicizing the benefits of gas declined “just when activism was increasing and going after the pipeline space…The reality, though, is that when you actually go out and talk to the constituents, there’s a tremendous amount of support for our industry and for the natural gas story.”

Talk to people and you’ll find that they want “heat in the wintertime. They want lower utility bills. They want cleaner air,” Zamarin said. “Right now we’re burning fuel oil, and the asthma rates in public housing in New York City could be cut dramatically by converting to natural gas…The pipeline industry was an out of sight, out of mind industry for a long time, very nonpartisan. But we now find ourselves in a much different environment.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |