E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Rebranded Appalachian E&P Eyeing Bigger Role as Shale Era Evolves

A junior independent working in Appalachia, backed by private equity, has rebranded to reflect the next era of shale development in the basin, one in which management believes the company can prosper despite an array of challenges facing the industry.

Huntley & Huntley Energy Exploration LLC, a partnership formed in 2012 between Blackstone Group Inc. and long-time shallow operator Huntley & Huntley Inc., is now Olympus Energy LLC. The company was formed to aggregate a land position in Southwest Pennsylvania, and for the following three years, it did just that.

However, with Pittsburgh-based Huntley & Huntley, a more than 100 year-old company that’s worked in Appalachia and other basins across the country, lacking experience in the unconventional space, Blackstone built a revamped management team that includes former executives of CNX Resources Corp, Chesapeake Energy Corp., EQT Corp., Pioneer Natural Resources Co. and the defunct Anadarko Petroleum Corp., now part of Occidental Petroleum Corp.

At a time when activity is slowing in the basin and as public companies are facing increasing pressure for better returns, Olympus CEO Chris Doyle thinks there’s room to grow and take on a bigger role in the nation’s largest gas-producing basin.

“We’re at a junction within the industry, and certainly within this basin, where companies that were leading at one time are going to find themselves behind the eight ball a little bit,” he told NGI’s Shale Daily during an interview on the sidelines of a recent industry conference in Pittsburgh. “And there are going to be emerging companies, like the one we have, that can actually be leaders in the basin.”

Doyle took the helm at Olympus in 2016 after a stint overseeing Chesapeake’s Appalachian and Powder River Basin operations. Prior to that, he spent 18 years at Anadarko in various roles, including as vice president of operations for the Southern and Appalachian region.

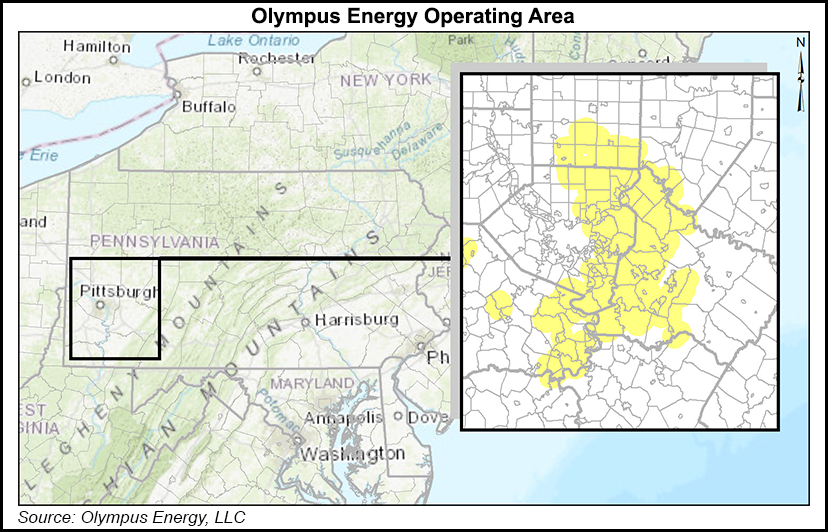

When he joined Olympus, the company had about 60,000 net acres. Today it holds 100,000 net acres, cobbled together in acquisitions and swaps as the basin was being consolidated by larger public operators.

“It’s difficult at times to get the attention of large public companies,” Doyle said. “I can say that because I spent the majority of my career at large public companies. I can remember the early days with Anadarko in the Marcellus and there was this small, private company that wanted to do some trade that didn’t mean a whole lot to me as an Anadarko representative.”

That small company was the former Rice Energy Inc., which was acquired by EQT Corp. in an $8 billion deal.

“Now the tables are turned, and I’m trying to get the attention of EQT, CNX, Range Resources,” Doyle said.

Olympus produces roughly 85 MMcf/d. In October, when Doyle spoke with NGI’s Shale Daily, the company had about 10 Marcellus wells drilled. This year’s plans had included drilling eight wells.

“Next year will be similar; come in, drill, use cash flow to complete wells, bring them on,” he said. “It’s a moderated approach.”

Much of the challenge for Olympus to date, Doyle said, has been the area it operates in, a hemmed in position that straddles rural Westmoreland County and suburban Allegheny County outside Pittsburgh.

“That’s difficult, not just the opposition to overall development” in some of the areas, Doyle said, “but making sure you have appropriate land use, making sure you can get pipelines installed and connect your gas up into the market. All those things took time to completely rearrange the way we were thinking about development as a company.”

While a plethora of wells have been drilled in the Marcellus, Utica and Upper Devonian shales around the company’s position, giving its crews a “pretty good idea of what the rock should do,” Olympus is still delineating some of its footprint and determining how best to apply new technology and management’s vision for maximizing returns in a low price environment.

“We also know it’s important for a small, private company like ourselves to build a base of production to build up a borrowing base, which we’ve done, and we’re going to continue,” Doyle said. “But we’re not going to be very aggressive and don’t need to be.

“We’re a small private company, I’m not kidding you about anything, but we’re focused on the right things…The market is sending a very clear signal, which is stop drilling,” Doyle said.

Management is keenly aware of the current environment and has aimed to maximize margins for its stakeholders amid a supply glut that’s crushed what companies were built for in the previous unconventional era of growth-at-all-costs.

The company gathers its production, cutting third-party expenses, spends within cash flow and is closely examining which assets can deliver the most value.

“What wasn’t part of the plan back in 2016, but what is certainly a part of the plan today, is what do we do with the Utica. We talk about it at every board meeting, I call it the $1 billion decision, because it’s that significant of a resource,” Doyle said. “Does it make sense now to jump out and drill one at $2 gas, no, probably not, but we’ll be ready. We see that as not our primary target today, but fast forward a few years, and I think it’ll be right there with the Marcellus.”

Doyle’s sentiments reflect those of the management teams of CNX, Range, EQT and other large operators that have talked about a bigger future for the deep Utica in Pennsylvania, where single wells have come online at more than 70 MMcf/d.

As it moves forward, Olympus is working to distinguish itself as a smaller unconventional operator that can contribute to the future of the basin as the operational landscape shifts. That’s one reason the company changed its name; it was being confused with its older minority owner, Huntley & Huntley.

Blackstone still owns a majority of the company. Doyle acknowledged that Olympus could eventually be taken public, sold to a larger operator or continue growing.

“We’re really happy with the asset that we’ve created,” he said. “I’m also a realist. We’re not here to drill wells, complete wells; we’re here to make money. If that means we’re going to go headlong into development, fantastic. If that means someone else sees the value in our assets and they can accelerate value for our shareholders, we’re going to do that.

“You have to look at all those avenues, and one of them will pop up, and it will become obvious that that’s what we’re going to do.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |