Regulatory | NGI All News Access

Potential Loss from Outlawing Unconventional Drilling Techniques Could Cost Mexico $45B by 2040

A ban on hydraulic fracturing (fracking) used in unconventional drilling could prove severely damaging to the Mexican economy, according to a study by consultancy Welligence.

Vice President Pablo Medina, who oversees analysis at the consultancy, discussed with NGI’s Mexico GPI legislation proposed to ban fracking in the Mexico energy industry by Sens. Martà Batres and Antares Guadalupe Vázquez. Both are members of the ruling Morena party.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has also said he is against fracking. In July he vetoed an approval by upstream regulator Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH) for state oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) to use the technique for two contracts in the Tampico-Misantla Basin.

Energy Secretary RocÃo Nahle has supported the responsible use of modern fracking techniques that may be used in harmony with the environment.

The president will have to “decide whether to achieve the goals as stated in Pemex’s business plan or to appease the environmentalist lobby,” Medina said. Clearly, he said, this is a make-or-break moment.

“The decision comes down to economics, given the pressure Pemex would feel if 30% of its 3P [proved, probable and possible] reserves were wiped out overnight.”

A new report by Welligence indicates a fracking ban would fly in the face of the principles that the two Morena senators espouse by dealing “serious fiscal economic and social blows to Mexico.” Researchers found that prohibiting the technique, which has been used for decades, would cancel investments of up to $1.3 billion in 2020 and $45 billion by 2040.

“The risk is real and more so as it concerns increasing gas imports,” something that López Obrador “has clearly stated he wants to avoid,” Medina said.

In response to a request under rules on freedom of information, the CNH revealed that fracking has been used in about one of every four wells in Mexico since 1996. As in many other countries, including the United States, it has been used to produce unconventional shale and tight oil and gas reservoirs. Mexican regulations on fracking were established in 2017.

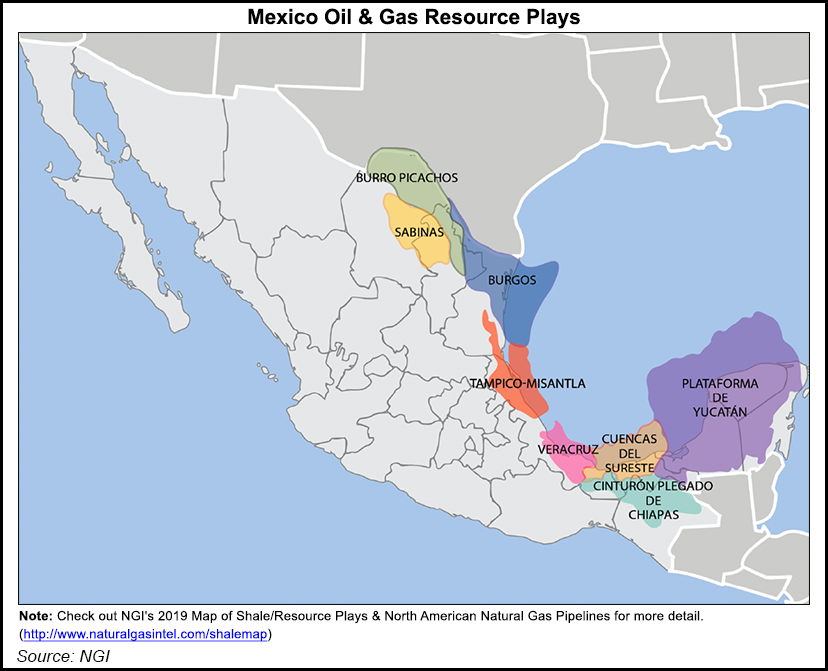

Pemex’s 2019 budget includes 3.35 billion pesos, or about $170 million, for three unconventional pilot projects in the Burro-Picachos, Tampico-Misantla and Burgos basins, and the CNH has sanctioned fracking at four exploration blocks in Tampico-Misantla.

A fracking ban, according to the report, would mean the goals set out in the recently published Pemex business plan would be impossible to meet. Meanwhile, it would cost the Mexican economy an estimated $7 billion in royalties and other charges through 2040.

Regional development would be particularly badly hit. States such as Veracruz on the central Gulf coast, and stretching as far as Chihuahua to the north on the U.S. border, house the major Tampico-Misantla and the Burgos basins, regarded as holding large shale/tight deposits. Fracking would also be needed to ease tight deposits in the southeast of the country, including Tabasco.

Tens of thousands of job opportunities could be nipped in the bud.

It’s important to note, according to the Welligence researchers, that unconventional drilling using fracking is no longer confined to the United States. Once relatively desolate areas of Canada and Argentina have been transformed into poles of prosperity.

The International Energy Agency has calculated that Mexico’s unconventional resources, between 2025 and 2040, could yield more than 400,000 b/d of crude and 1.4 Bcf/d of gas. That would amount to almost one-third of current oil production and more than one-third of current gas production.

Welligence called for an open, technical debate on the proposal of a plan. That is also the view of analyst Ramses Pech, CEO of the Caraiva y Asociados consultancy, who writes regularly for daily La Jornada which, of Mexico’s leading newspapers, is the most supportive of López Obrador.

“The elimination of hydraulic fracturing would throw years of experience gained in facing the challenges of unconventional resources,” Pech told NGI’s Mexico GPI. “It would reduce the Mexican industry to the southeastern basins of the country and shallow waters offshore the states of Campeche and Tabasco.

“It would close the spigot on the immense potential for gas and condensates in areas further north such as the Burgos and Tampico-Misantla basins.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |