Infrastructure | NGI All News Access

Pipelines Key to Two Oregon LNG Projects, Backers Say

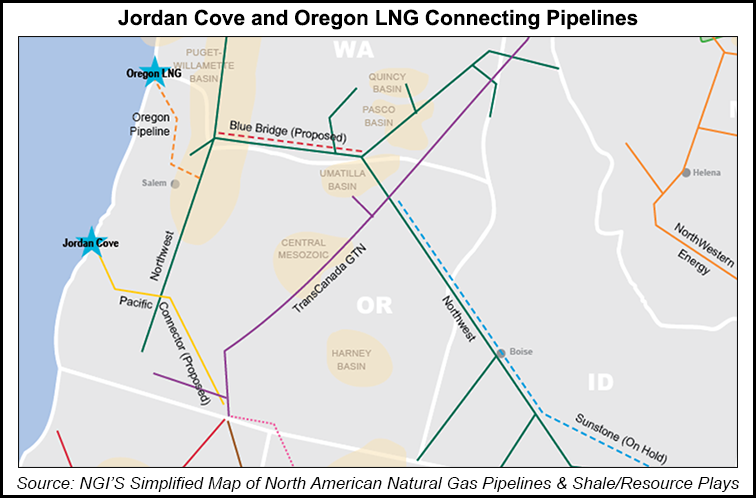

A lot of under-used natural gas pipeline capacity from supply sources on both sides of the U.S.-Canadian border is a key competitive advantage for two proposed liquefied natural gas (LNG) export projects in Oregon, according to backers of the Jordan Cove and Oregon LNG projects.

Bob Braddock, Jordan Cove LNG project manager, told NGI that he agrees with the assessments by industry stakeholders at a recent conference in Calgary that the two western U.S. projects have advantages over the proposed projects in a remote area of northwest British Columbia (BC) (see Daily GPI, Sept. 23).

“The premise we have had all along was that we have an existing pipeline system that gets you most of the way [to the proposed Jordan Cove terminal] for Canadian [supply sources] to use,” Braddock said. “And it is under-utilized.” According to the TransCanada GTN Pipeline website, on Friday there was nearly 1 Bcf/d of unused capacity at Malin, in southern Oregon, where Jordan Cove proposes to interconnect via the Pacific Connector, a new, 234-mile, 36-mile diameter transmission pipeline.

Existing large-diameter pipeline capacity from robust Canadian and U.S. sources, and the fact that the Canadian projects’ proposed connecting pipelines face a series of uncertainties, put the BC projects at a serious disadvantage, according to Oregon LNG CEO Peter Hansen.

Despite the fact that the distance for taking BC supplies down to Oregon is a lot farther than the proposed coastal export facilities in Canada, the cost to reach U.S. projects turns out to be much less, according to Braddock, who added that his project also has the capability of getting gas from both U.S. and Canadian basins.

“There is far less uncertainty down here because the pipelines needed to be built in the United States are far less complicated and the regulatory process has so much more clarity down here. We don’t have the First Nation issues that they have up there, and which tend to hang over everything [in Canada].”

Braddock and Hansen earlier this year argued for the favorable economics of their projects, compared with the proposals for BC (see Daily GPI,May 20). Both projects expect export permits for non-free trade agreement (FTA) nations at the end of this year and construction approvals by the end of next year.

“They have to run pipelines over the Canadian Rockies, and some of these pipelines are said to cost up to $1 billion, so I think we have a significant cost advantage,” Hansen told NGI. Some potential investors in the BC projects are putting off making a decision on whether or not to proceed with financing on the projects, he said. “They have been ready to go ahead for years [with Kitimat], and they are probably not going to be ready in two years.”

Hansen said that some small and medium-sized producers holding both BC and Alberta supplies have expressed interest in shipping supplies into Oregon for export.

Worries reportedly continue among large producers who are sponsoring BC LNG projects, such as California-based Chevron Corp.’s Canadian unit, Chevron Canada, Hansen said. They are concerned about a possible $100 million in added annual tax bills from the Liberal BC government, and still unresolved First Nation issues. Hansen said the latter may be the “800-pound” gorilla in the room regarding Canadian participation in gas exports.

A number of different native groups are claiming ownership of the same lands in western Canada, and their disputes so far have not been resolved. As a result, there are multiple groups claiming they want to negotiate pipeline routes crossing their lands.

“No one knows who to negotiate with,” Hansen said. “This is not something you can settle easily and it is not the type of thing that can be resolved through legislation, so legally it is the type of thing that could take 10 years to settle.”

Along with growing uncertainties among its Canadian competitors, including eventual project financing questions, Hanson said his project has ready access to large supplies of newfound gas in both BC and Alberta, and small and medium-size producers are indicating they are interested in talking to the U.S.-based projects.

Hansen said he was recently approached by a medium-sized producer in western Canada that indicated it had 10 Bcf/d of supplies to market in Asia. “When you start adding up the numbers these producers are throwing around, there is so much gas we [in the U.S. projects] can only scrape the surface,” he said.

Hansen pointed out that many of the backers of BC export projects include some of the global energy giants that have invested in new liquefaction projects in Australia and elsewhere on the Pacific Rim. They are adamantly sticking to global oil-tied LNG pricing, something Hansen thinks the Japanese are going to increasingly reject.

“We were at the consumer-producer LNG conference in Tokyo earlier in September, and just like last year, the Japanese stood up and said they were not going to accept oil-based contracts anymore, and all the majors stood up and walked out,” he said.

The Oregon projects do not intend to be owners of the gas supplies flowing through their export facilities. Instead, they plan to find tolling customers in the Far East to put together with the Canadian producers looking for a foot in the Asian markets.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |