Infrastructure | NGI All News Access

Pipeline Tragedy, Fuel Supply Crisis Expose Vulnerability of Mexico Oil, Gas Infrastructure

A deadly gasoline pipeline explosion in Mexico last Friday, combined with the fuel supply crisis that preceded it, have exposed the vulnerability of the country’s oil and gas infrastructure, according to experts.

The death toll from the blast, which occurred along the Tuxpan-Tula fuel pipeline near the town of Tlahuelilpan, Hidalgo state, had reached 93 as of Tuesday, with 46 people still hospitalized, Health Minister Jorge Alcocer said.

Prior to the explosion, a leak in the pipe caused by an illegal tap attracted throngs of people seeking to collect the fuel, which has been in short supply amid President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s campaign to stamp out “huachicoleo,” a colloquial term for fuel theft.

Military personnel at the site tried unsuccessfully to disperse the crowd and secure the area prior to the blast, according to López Obrador.

Security minister Alfonso Durazo told reporters on Sunday that national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) shut off the pipeline on Friday at 6:20 p.m., four hours after the illegal tap was detected. At 6:52 p.m., with gasoline still flowing through the pipe, the fatal explosion occurred.

As part of the fuel theft crackdown, which began in late December, the military began shutting down Pemex pipelines that were known as popular targets for thieves or “huachicoleros,” including Tuxpan-Tula. While the number of illegal taps dropped significantly, the measure led to widespread gasoline shortages and filling station closures, with lines of cars stretching for blocks in some cases.

As the supply crisis worsened, Pemex reopened Tuxpan-Tula last Wednesday (Jan. 16), CEO Octavio Romero Oropeza told reporters last Saturday (Jan. 19). López Obrador said Monday the government had signed contracts to purchase 571 tanker trucks from the United States, which would increase Mexico’s fuel distribution capacity by 25% while the pipeline supply issues were being resolved.

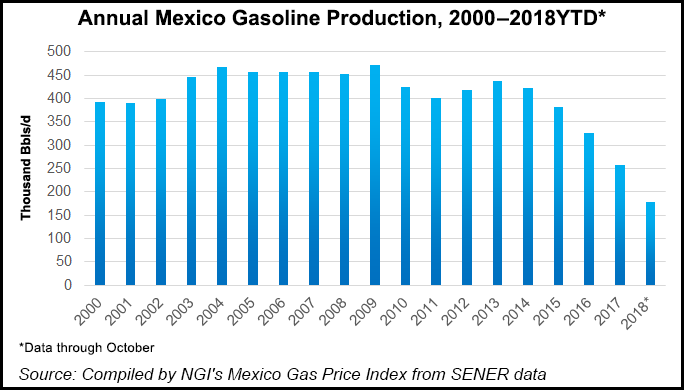

“There is a fundamental reason” for the fuel supply crisis, “which is the fact that in Mexico we don’t have an equilibrium between supply and demand,” Marcos y Asociados energy consultancy partner Luis Miguel Labardini told NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index.

Citing that Mexico only has 2.5 days’ worth of gasoline storage capacity, compared to 90 days in the United States, Labardini said, “Pemex has to always guess how much fuel to buy, and how much fuel to transport, because basically there is no spare capacity in Mexico.”

Natural Gas Infrastructure Challenge

Though natural gas pipeline theft is not an issue in Mexico, a lack of adequate gas storage could also prove troublesome down the road, according to GMEC energy consultancy founder Gonzalo Monroy.

“Mexico doesn’t have any real natural gas storage,” Monroy told NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index, which “speaks volumes about the vulnerability of the system.”

Mexico’s national pipeline grid operator Cenagas last March published a public policy for gas storage, which called for installing five days’ worth of underground capacity by 2026. Mexico currently relies on the Altamira and Manzanillo liquefied natural gas terminals for system balancing.

In a white paper prepared by the energy ministry for López Obrador’s transition team, officials stressed the importance of continuing the implementation of the storage policy. The current gasoline shortages, meanwhile, “are a direct result of not investing enough in storage,” Monroy said.

The parallels between oil products and natural gas don’t stop there, according to Labardini, who said insufficient rule of law and poor corporate governance at Pemex also have impeded developing vital infrastructure for both products.

Hidalgo, where the explosion occurred, is the same state in which TransCanada Corp. has faced repeated delays to its Tuxpan-Tula and Tula-Villa de Reyes natural gas pipeline projects, citing intractable conflicts with the local government and the pending completion of an indigenous consultation process by energy ministry Sener.

“There are supposed to be legal means” to solve conflicts,” Labardini said, “but those legal means do not provide a prompt and fair solution to the problems…I think these are the same issues” affecting oil products and natural gas.

The fact that Pemex is 100% state-owned also has contributed to the problem, Labardini said, explaining that if Pemex had to answer to shareholders, it almost certainly would have installed cutting-edge technology throughout its pipeline network to more quickly detect illegal taps.

“Pemex belongs to everyone and doesn’t belong to anyone,” Labardini said, adding that, “if somebody took ownership of the fuel, Pemex would have the right technology and the army would have been there much earlier, because Pemex would have detected the [scale] of the problem.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |