NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

Oil Shale Development Requires Billions of Gallons of Water, Sportsmen Say

An environmental group focused on recreation says industrial-scale development of oil shale is harmful to rivers and could require billions gallons of water annually, significantly more than what would be needed for hydraulic fracturing (fracking).

Oil shale — which is often confused with “shale oil” — is a fine-grained sedimentary rock that contains kerogen, a solid mixture of organic chemical compounds. While shale oil can be produced in a similar method to shale gas, oil shale development requires large amounts of heat and pressure to separate the kerogen from the rock. Ultimately the process can yield jet and diesel fuel, kerosene and other products.

According to a 13-page report released Nov. 15 by Sportsmen for Responsible Energy Development (SRDC), oil shale development could threaten river flows, fish and wildlife habitat in Colorado, Utah and Wyoming, especially in the Colorado, Duchesne, Green, Uintah and White river basins.

“After more than 100 years of trying, we are still several years away from an economically viable oil shale industry,” Melinda Kassen wrote in the report, “Water Under Pressure.” She added that “the technology is unproven and the potential environmental impacts are unknown.

“For a resource that lies in the midst of the semi-arid West, with sparse precipitation and few large rivers, it is not clear where the water would come from, or how it would affect the fish that live in the local streams. With the region already straining its water supply and facing continued population growth, finding another increment of water for oil shale, while protecting native and sport fisheries, may be an insurmountable challenge.”

Kassen cites separate figures from the Interior Department’s Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) and its Bureau of Land Management (BLM), as well as the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

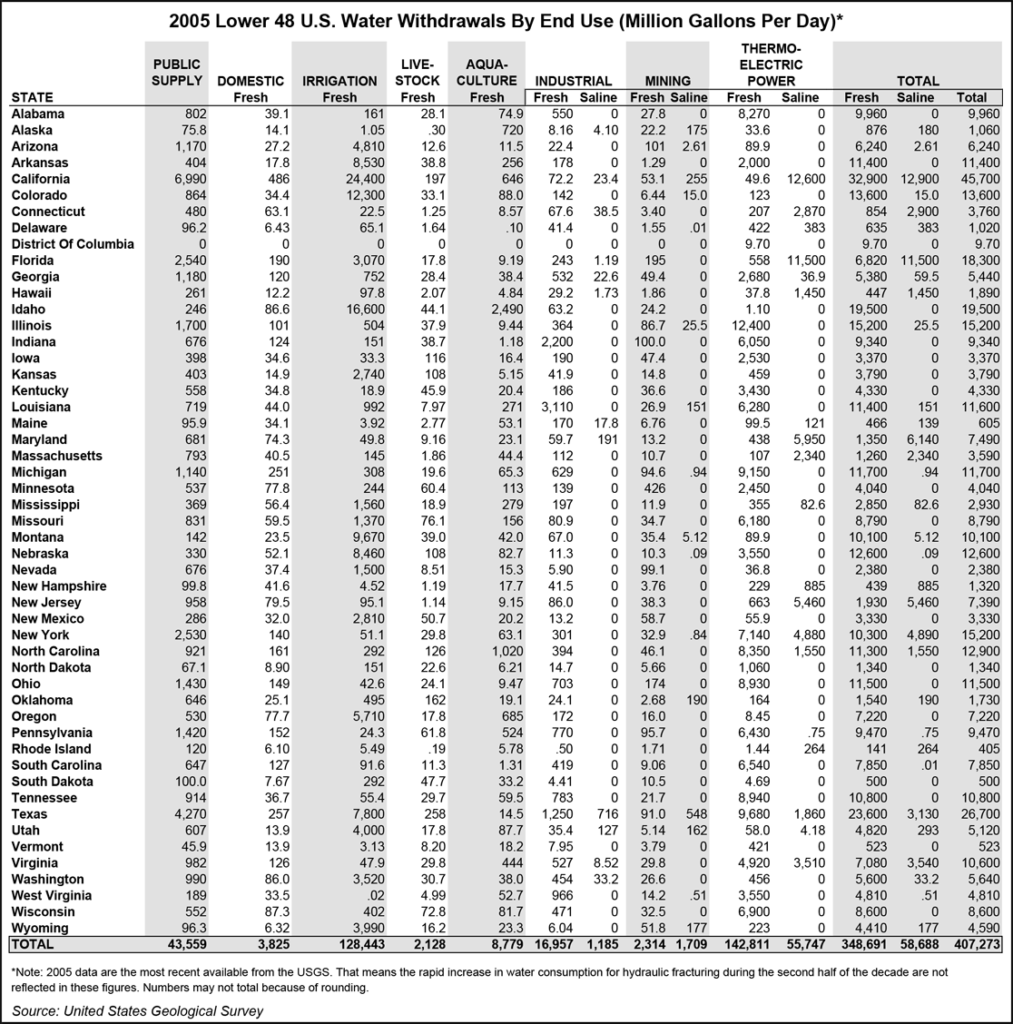

The USBR reported that oil shale development could require up to 120,000 acre-feet (39.1 billion gallons) of water every year by 2060, depending on demand. But Kassen said additional studies said full-scale oil shale development could use as much as 400,000 acre-feet (130.4 billion gallons) of water per year.

According to the GAO, recovering one barrel of oil from oil shale would require between one and 12 barrels of water, and between 22 and 56 gallons of water would equal one BTU produced by oil shale. Meanwhile the BLM asserts that mid-point water use for oil shale production totaling 1 million b/d using current technology would require 363,000 acre-feet (118.3 billion gallons) of water annually.

“The most remarkable aspect of all these numbers is their comparison to traditional fossil fuel development,” Kassen said. “Oil from shale has a much higher energy intensity than other sources of energy; that alone makes its water requirements higher than other sources of fuel. Adding in its other water needs only makes the comparison worse.”

Kassen includes in her report that the GAO calculates that conventional natural gas development would require 1-3 gallons of water/BTU, while unconventional shale gas that uses fracking would require between 0.6 and 3.8 gallons of water/BTU.

“The [SRDC] are rightly concerned that industrial scale oil production could deplete stream flows, degrade habitat [and] cut off wildlife migration corridors along important rivers,” David Moryc, senior director for the environmental group American Rivers, wrote in a blog post Tuesday. “All of this will of course affect hunting, fishing and the local economies that depend on more sustainable industries.”

Last August, more than 100 business, conservation and sporting groups sent letters of support to the BLM, which had proposed in February reducing the amount of land available for oil shale research and development in Colorado, Utah and Wyoming (see Shale Daily, Aug. 20; Feb. 6).

Meanwhile, the GAO said in August 2011 that oil shale development’s impacts on water supplies were difficult to quantify, but in a report issued nine months earlier predicted that the practice would be hampered by the availability of water in the arid West (see Shale Daily, Aug. 26, 2011; Dec. 2, 2010).

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |