Infrastructure | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Regulatory

NY Part 2: New York Freezing Out Marcellus NatGas Infrastructure

*Part two of four. This series examines the effects New York state’s energy policies are having on Appalachian natural gas producers, consumers and the Northeast. It explores the political, operational and economic issues related to the state government’s position on natural gas. Part two explores New York’s seeming blockade of natural gas and how that’s impacted the Appalachian Basin and efforts to get more supplies to places like New England.

The Marcellus and Utica shales have transformed Appalachia into one of the world’s largest natural gas producing regions, but a few hundred miles to the northeast, New England is starving for more — thanks in part to New York energy policy.

At a watershed moment, during a time when long-needed pipeline capacity is coming online that could alleviate constraints in a lasting way, those in the industry believe New York is obstructing the energy benefits of other states and most notably freezing out New England.

Under Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo, the state has not only banned high-volume hydraulic fracturing, but it’s thwarting shale gas infrastructure.

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) has denied key water quality certifications (WQC) for both National Fuel Gas Co.’s (NFG) Northern Access expansion project and the Constitution Pipeline, preventing more than 1 Bcf/d of natural gas from moving eastward and beyond. DEC also on Wednesday (Aug. 31) denied Millennium Pipeline Co. LLC a WQC for its Valley Lateral Project, which would serve a gas-fired power plant under construction in the state. The agency said FERC’s environmental review was inadequate.

“As the federal government abdicates its responsibility on climate change, New York is a driving force for protecting our natural resources for future generations and ensuring New York’s environmental review process is the strongest in the nation,” DEC spokeswoman Erica Ringewald told NGI’s Shale Daily. Cuomo said in his 2017 state-of-the-state address that New York must “double down by investing in the fight against dirty fossil fuels and fracked gas from neighboring states.”

Given that position, it’s not inconceivable to think that Appalachian natural gas might make its way from Pennsylvania to the Gulf Coast for liquefaction, before being put on a tanker and passing through Canada to New England, said BTU Analytics LLC analyst Matt Hoza.

“The bigger problem is for New England in the long-term. Producers in northeast Pennsylvania, north-central Pennsylvania — they’re going to have projects out of the basin — maybe not as many projects as they want, but they’ll still achieve growth,” he said. “You have to pretty much pass through New York to get to New England, and that’s not going to happen.”

To be sure, the DEC has approved seven WQC for interstate natural gas pipeline projects in the last five years, but those were mostly small projects that expanded existing systems.

Developed in response to natural gas demand in New York and New England, Constitution was originally expected to be in service by March 2015. Cabot Oil & Gas Corp. would be the pipeline’s largest shipper. Similarly, the Northern Access project was scheduled to enter service in late 2016. NFG affiliate Seneca Resources Corp. is its only shipper.

Now that the companies are challenging the DEC’s denials in federal court, Constitution isn’t expected to enter service until 2019. Northern Access could be delayed until 2020. That’s if the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission-approved projects are even built.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit recently denied Constitution’s challenge, ruling DEC is entitled to a WQC review under relevant federal laws. The company has filed a petition for the court to rehear the case en banc, or before all of its active judges, arguing that if the three-judge panel’s opinion is allowed to stand it could have far-reaching implications for natural gas infrastructure projects across the country.

“It was frustrating when Gov. Cuomo denied Constitution that permit,” said Cabot spokesman George Stark. It was elected officials, he said, who first “took to the airwaves to talk about how that action in New York is setting back Pennsylvania. The landowners are in Pennsylvania, the work is taking place in Pennsylvania, the wages are in Pennsylvania. All those pieces are now stopped due to the pipeline being stopped. It’s a trickle down effect.

“What we know is that beyond New York, New England as a region is starved for natural gas.”

Stranded

Make no mistake about it, said Northeast Gas Association CEO Thomas Kiley, New England needs more natural gas, particularly on peak winter demand days. Nearly 50% of the region’s electricity is generated with natural gas and other fuel sources are scheduled for retirement through 2020, according to the Independent System Operator of New England (ISO NE). Kiley added that the state’s local gas distribution companies (LDC) have added about 340,000 new residential and commercial customers over the last decade.

Kiley, however, has a difficult job at times. Working from a Boston suburb, his organization’s message often falls on deaf ears; New England has generally opposed shipping more natural gas in via pipeline, a position that’s been compounded by New York’s recent denials.

“The Northeast, quite frankly, isn’t very hospitable for any new energy infrastructure project,” Kiley said, when asked about the social appetite for natural gas consumption in New England. “I think getting sited — getting any energy infrastructure sited in the Northeast — is a real challenge. It’s not just natural gas pipelines; it’s wind farms, it’s solar fields.”

While shale supplies have lowered energy prices in New England over the last decade, the dearth of pipelines has created volatility. Liquefied natural gas imports have historically met a significant portion of demand in the region, but those have declined due to various conditions, such as demand from other markets and contracts expiring. Pipeline constraints have pushed prices upward during severe cold. Prices at Algonquin Citygate reached $25/MMBtu and $15/MMBtu during the winters of 2014 and 2015, respectively.

Pipeline capacity in the region is often reserved by LDCs on the worst winter weather days. “On the coldest days, when those interstate pipelines are running at capacity or near capacity, those volumes go to LDCs and there’s not a lot of gas left over for power generators that don’t have firm transportation,” Kiley said. “As a result, there are other means that have to be employed by ISO NE. That causes prices to spike. If we had more pipeline capacity, that would help the consumers’ electric bills.”

Projects like Northeast Energy Direct and Access Northeast have been canceled or suspended because the market fails to incentivize firm transportation for power generators, Kiley said. But he added that New York’s position on natural gas is “concerning.” His organization represents transmission companies in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, as well.

“You know there’s not really an anti-gas sentiment amongst the entire New York state government, but there have been delayed projects and it does have an impact,” he said. “Our member companies are still working together trying to build more projects.”

Indeed, after years of oversupply, there’s a bevy of Appalachian projects slated to come online through 2020. Some of those are aimed at moving Appalachian gas east. Of the 20 projects in the queue that represent about 17.5 Bcf/d of takeaway, RBN Energy LLC said four of those would move nearly 3 Bcf/d to the East.

“When you think about it, it’s kind of the broader impacts to the Northeast region because you do have a lot of projects expected to come online in 2019 and 2020,” said Williams Capital Group LP analyst Gabriele Sorbara. “With all the projects coming online, do we have excess takeaway capacity in the region? That could be a problem.”

East Daley Capital’s Managing Director Justin Carlson agrees. But he said an overbuild is “absolutely a matter of geography,” with southwest Appalachia more likely to suffer the effects. Projects like Northern Access and Constitution are sorely needed in northern Appalachia.

”Opportunity Cost’

At one point, Northern Access and Constitution were considered key to unlocking stranded gas in remote parts of the Marcellus Shale, but the companies have since turned their attention to other projects.

Industry supporters have argued on behalf of the companies in court that New York’s rejections have caused a loss of income across the supply chain, workforce reductions and shut-in wells. But to what extent the pipelines’ leading shippers have suffered financially and operationally is less clear.

“It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly what impact the delays have had on Seneca and Cabot without having a detailed financial model,” said NGI’s Director of Strategy and Research Patrick Rau. The delays, he said, have likely prevented both companies from booking more proved reserves. Not having that takeaway capacity “raises doubts” as to whether both companies can drill as many wells within the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s mandated five-year period. That’s likely dented stock prices, Rau said.

Seneca’s Appalachian production has ranged between 380-390 MMcf/d over the last three fiscal years, “so no doubt the lack of Northern Access has prevented that from growing materially.” And the production Northern Access has failed to add likely resulted in a “pretty sizeable opportunity cost for” NFG in terms of lost earnings, he said.

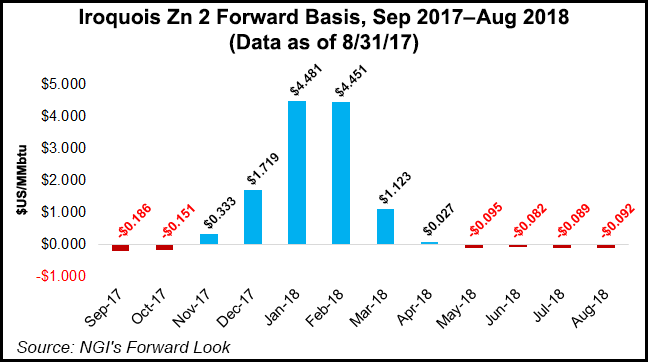

About 350 MMcf/d on Northern Access would move to the Niagara hub in Canada near the U.S. border and then onto the Dawn Hub. Another 140 MMcf/d would reach Tennessee Zone 5. Future Dawn basis might be watered down by other projects coming online, but those differentials are still better than the ones in northwest Pennsylvania, where Seneca produces, Rau said. He said, for example, that average Dawn basis for the next 12 months is roughly 70.7 cents higher than that of nearby Tennessee Zone 4 Marcellus.

Rau suggested a workaround for Seneca might be on the planned 1.5 Bcf/d Nexus Gas Transmission pipeline, which is not fully subscribed, to move Appalachian gas from eastern Ohio into Michigan and on to the Midwest and Canada. Hoza suggested the same, saying NFG could consider bypassing New York by pushing more gas westward. Nexus, Rau said, is only 65% contracted, leaving 500 MMcf/d available and making up the difference lost if Northern Access isn’t built.

While NFG is forecasting 10% growth over the next five years, Cabot’s path is clearer. “The delay in Constitution has been lingering for quite a while longer and that has given Cabot much more time to come up with alternatives,” Rau said.

Without Constitution, Cabot has lost the ability to access Iroquois Transmission and the possibility of huge price spikes during the winter. That’s made Atlantic Sunrise, which would expand the Transcontinental Gas Pipe Line system to move more Appalachian gas southeast along the Atlantic seaboard, that much more important for Cabot, Stark said. The company has 1 Bcf/d contracted on the proposed 1.7 Bcf/d system.

Along with Atlantic Sunrise, Cabot has since struck deals to supply two natural gas-fired power plants in northeast Pennsylvania and secured volumes on Tennessee Gas Pipeline Co. LLC’s Orion Project. As the company exits the year and heads into 2018, it has a clearer path to help double its Marcellus production, management has said.

“Constitution isn’t so much a must have for Cabot anymore, it’s more of a ”really, really nice to have’ for them,” Rau said.

Seneca plans to leverage existing infrastructure to maximize Utica Shale growth in northwest Pennsylvania. Management said in August that the plan would help offset the losses suffered since the DEC denied Northern Access. Beyond the upstream, the Empire System expansion is on track for an in-service date of November 2019, which would add 205,000 Dth/d to the system. The NFG Supply System expansion is also on track to come online in phases between the end of 2017 and 2019, which would add another 210,500 Dth/d.

The situation in New York is “not ideal for producers,” Hoza said. “But they’re putting their heads down and going forward with their growth plans.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |