E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

North America Takes Biggest Global Hit as Upstream Valuation Slumps $1.6T on Oil Price Crash

The oil price debacle, brought about in part by the demand-crushing pandemic, has wiped an estimated $1.6 trillion from the valuation of the global upstream industry, with North American losses leading the way, a new analysis by Wood Mackenzie has found.

Global upstream development spend overall this year has been knocked down by 30% from the pre-crash view.

“This figure captures the impact of Wood Mackenzie’s downgraded long-term Brent price assumption, now $50/bbl in 2020 terms, rather than the previous $60 — and much more,” said Upstream Vice President Andrew Pearson.

North America has taken the biggest hit, with Africa and Asia also slumping, and “these regions may never recover to pre-crash levels,” said Wood Mackenzie’s team.

In the United States, capital expenditures (capex) are down by around 39% from the pre-crash view, with the Permian Basin most affected.

“The record low prices and near-full storage tanks forced some operators to shut-in production,” researchers said. However, the Permian, as the most active U.S. play, should lead the recovery, with 85% of supply growth through 2025.

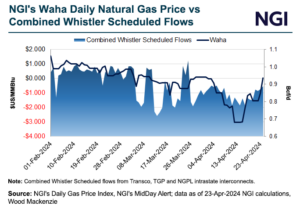

Moreover, falling associated gas volumes from the Permian could lead to higher gas prices.

The U.S. Gulf of Mexico (GOM), meanwhile, was “better prepared to weather the downturn this time,” because operators were “already lean and nimble after the last crash,” according to Wood Mackenzie’s team. “The region is resilient at low oil prices and more than 80% of oil production has a short-run marginal cost of $10 Brent.”

The GOM “remains afloat,” but the budget cuts have been deep, with some fields shut-in because of the low prices, while investments, exploration and final investment decisions (FID) all undergoing “major calibrations.”

Only nine major FIDs are expected worldwide this year, versus the firm’s earlier projection of close to 50.

“The oil price crash and the market uncertainty it caused has affected all regions, all operators and all resource themes,” said upstream Vice President Fraser McKay. “In early March, we anticipated the industry’s response would be rapid and decisive. It has been. Tough calls have been made, despite a lack of clarity” on how the Covid-19 pandemic will impact oil and gas demand, McKay said, “both in terms of depth and duration.”

Production cuts by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and its allies, aka OPEC-plus, reshaped the near-term supply outlook too. Tight oil and heavy oil cash flows have suffered the most, “but overall resilience has improved since the last downturn.”

Oilsands and heavy oil valuations are down the most in percentage terms, off by more than 50%, but overall, “more than $1 trillion was wiped off conventional onshore and offshore projects,” researchers said.

“There is no hiding how sensitive Canada’s oilsands sector is to pricing — expected cash flows have fallen by more than $32 billion from our pre-crash view,” researchers said. “Gas plays in Alberta and British Columbia are also exposed to the downturn, but not nearly to the same extent.”

Canadian upstream investment is set to decline by more than $8 billion this year.

“With Canada having never fully recovered from the 2015 downturn, 2020 capital spending is now expected to be nearly 80% lower than 2013 levels,” researchers said.

Wood Mackenzie’s team also found that more than 40% of future projects now are expected to generate an internal rate of return of less than 15%.

“To date, cuts to expenditure have largely been in line with our expectations,” Pearson said. “New project spend has stagnated and output has been curtailed, most notably among OPEC-plus participants and in the U.S. tight oil sector.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |