NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | E&P | Infrastructure | LNG | LNG Insight | Markets | NGI All News Access

NGI 2020: More Price Pain in Store for Natural Gas Bulls, but LNG Brings Hope in New Decade

Editor’s Note: This is one of a 14-piece series NGI undertook as the energy industry readied for the new year, with Lower 48 natural gas and oil supply continuing to surge in an uncertain environment as liquefied natural gas exports ramp up, Mexico markets remain shrouded and stakeholders demand more value. Get your complimentary copy of NGI’s 2020 Special Report today.

Amid bargain basement prices and stubbornly mild January temperatures, 2020 has gotten off to an inauspicious start for natural gas bulls. Henry Hub futures have barely held above the $2 mark in the dead of winter, and the curve has offered little hope for a return to $3-plus.

Still, the glut of Lower 48 production — not necessarily a lack of structural demand — has been the albatross dragging down prices, and 2020 could prove a pivotal year in terms of the trajectory for U.S. onshore development and output, especially for gas-focused plays.

One thing prognosticators seem to agree on: the prodigious production growth of the 2010s won’t continue into the new decade.

After measuring annual growth of 8-9 Bcf/d for 2018 and 2019, analysts at Enverus project incremental year/year dry gas production of around 2 Bcf/d for 2020, driven by growth in the Northeast and out of the Permian Basin. That’s based on early guidance from exploration and production (E&P) companies and assumes $55/bbl West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and $2.50/MMBtu Henry Hub.

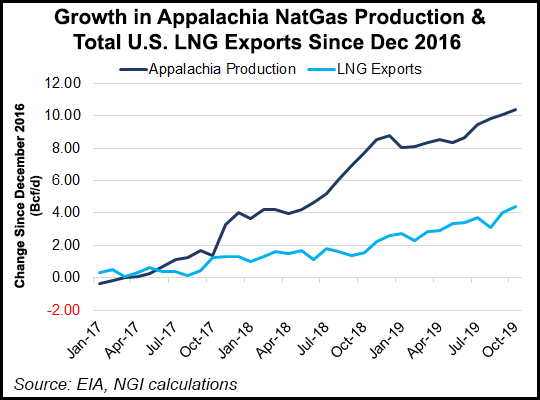

Meanwhile, on the demand side, Enverus projects domestic demand (residential/commercial, power and industrial) will average 77.2 Bcf/d in 2020, a 0.3 Bcf/d increase compared to 2019. The major growth driver for demand over the next five years will be liquefied natural gas (LNG), expected to grow from 6 Bcf/d in the summer of 2019 to 10 Bcf/d by 2024, according to the firm.

“Natural gas production has been increasing rapidly since 2006, with a notable growth acceleration taking place starting 2017,” said Enverus’ Rob McBride, senior director of strategy and analytics at the firm. “In the past three years, some areas grew by 32%, or 23 Bcf/d. However, we’ve also seen a steady drop in prices” that’s been “challenging for producers.

“In 2019, natural gas demand in the U.S. averaged only 6% higher than normal. Add to that pipeline constraints and clear signals from operators that they’re at a breaking point, and the writing on the wall becomes pretty clear — we’re expecting a significant slowdown in the growth of U.S. natural gas production” for 2020.

With 4Q2019 earnings season just around the corner, the capital expenditure (capex) picture for 2020 points to “significantly lower spend” not just in the upstream but midstream and downstream as well, according to Enverus.

Looking at data gathered from a sample of 24 companies, liquids-weighted producers are averaging a 5% reduction in 2020 capex, with gas-weighted producers showing a 25% reduction, the firm said.

EQT Corp. and Chesapeake Corp. together account for a $1.1 billion reduction in 2020 spend, and six Appalachia pure-players — EQT, Cabot Oil & Gas Corp., Southwestern Energy, Antero Resources Corp., CNX Resources Corp. and Montage Resources Corp. — collectively are expected to reduce capex by around $1.5 billion, Enverus said.

Still, even with a challenging commodity price environment, the supply response from gassy producers might not occur as quickly as price bulls would want.

“Even if prices continue to plummet, the market response is likely to take time,” according to analysts at EBW Analytics Group. “Historically, even if prices fall, it typically takes six to nine months for producers to adjust their drilling programs. Further, several of the largest producers are on the hook to pay for firm transportation rights on pipelines added in the past two to three years.

“These ”take or pay’ obligations typically cost around 70 cents/MMBtu,” the EBW analysts said. “Even if the price of natural gas is insufficient to cover all of the producers’ costs, it may still be in their interest to sell natural gas, to cover at least a portion of their sunk costs and generate enough cash flow to service debt.”

Production growth appears poised to slow sharply in 2020, but those hoping for higher prices may have to exercise some patience.

Enverus expects 2020 prices to drop to $2.50 on average for 2020, down from $2.65 in 2019. The firm is modeling end-winter inventories of 1.7-2.0 Tcf, which it expects will exert downward pressure on the market.

Goldman Sachs is expecting Henry Hub to average $2.20/Mcf this year and $2.50 in 2021. A recent Evercore ISI sampling of data collected from more than 250 oil and gas operators showed price decks on average predicting $2.37/Mcf for natural gas in 2020.

The Energy Information Administration, meanwhile, expects Henry Hub prices to average $2.33/MMBtu in 2020.

EBW recently placed storage on a trajectory to exit winter at 1,712 Bcf. Such a pace would mean “vast oversupply conditions” this spring, putting inventories at their highest level since March 2017, when the market had 24.7 Bcf/d less production.

“Oversupply may create gas prices under $2/MMBtu — potentially forcing producers to sharply revise drilling programs this spring and, in conjunction with soaring LNG exports, help natural gas prices to rise toward the mid-$2.30s,” the EBW analysts said. “By late summer, however, fears of LNG shut-ins may reach a crescendo, leading to a relapse in Nymex futures toward $2.00-2.25.”

One might have to look beyond 2020, but there is hope on the horizon for natural gas bulls, especially as the next wave of LNG feed gas demand hits the market.

“While we remain bearish on gas fundamentals as we head into 2020, we believe the longer-dated forward curve has broken below sustainable levels to implore producers to meet demand needs in later years,” analysts at Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co. (TPH) said.

The firm is forecasting increased LNG feed gas demand in the 2023-2024 time frame that would require prices in the $2.75-3.00/Mcf range to incentivize the necessary production.

“Inventory over this time frame is not a key concern for most, as we see our Northeast coverage universe generally has 11-12 years of core inventory at 2020 maintenance level programs,” according to TPH, but the “picture changes quite a bit” in a sub-$2.50 pricing environment, as this would leave “several producers” unable to generate the necessary returns on their inventory.

“If our above-$2.75 longer-term call proves correct, the punchline is simple: survive in 2020 to thrive in 2023.”

Of course, most producers in the U.S. onshore won’t base their development plans on gas economics; associated gas from liquids-focused drilling — in the Permian Basin in particular — presents another major wrinkle when attempting to decipher production trends for 2020.

Increased crude oil takeaway out of the Permian has analysts at RBN Energy LLC expecting the spread between the Midland hub and the Magellan East Houston terminal to continue tightening in 2020.

“Our outlook doesn’t hold the same optimism for the price spread for natural gas between the Permian and the Texas Gulf Coast,” RBN analyst Jason Ferguson said in a recent note. “Like oil, Permian natural gas production continues to grow, recently topping 12 Bcf/d, and production in the basin is up about 2 Bcf/d over the last six months” coinciding with the start-up of Kinder Morgan Inc.’s 2 Bcf/d Gulf Coast Express pipeline.

Unlike oil, there are no takeaway pipelines from the basin slated to start up in 2020, Ferguson said. “This means that the natural gas pipelines in the Permian, which are already becoming constrained again, are set to be completely full sometime in the next few months. If you are wondering what happens to Permian prices when that happens, you need to look no further than last year.”

The Permian’s liquids-focused economics upended the West Texas natural gas market in 2019, sending spot prices to previously unheard-of lows. As pipelines filled up, producers found themselves paying to offload their associated volumes. Waha dropped to as low as negative $9/MMBtu last April during a sustained stretch of negative average prices at the hub.

“We have maintained a view for some time…that Waha is headed for the same price levels experienced last year,” Ferguson said. “The exact timing is always difficult to nail down, but our current models say that prices near zero, and negative on some days, are likely to reappear on a more consistent basis sometime in the spring.”

Exports to Mexico could relieve some pressure for Permian natural gas, as the final part of the Wahalajara system, the 0.9 Bcf/d Villa de Reyes-Aguascalientes-Guadalajara pipeline being developed by Mexican company Fermaca, should be online by the end of March, according to NGI’s Mexico GPI. When this happens, the system would be complete and allow gas from the Permian to reach Guadalajara, Mexico’s second largest city.

Meanwhile, the outlook for crude prices in 2020 remains far from settled, with markets greeted in the new year by a major escalation in Middle East tensions in the aftermath of the U.S. strike that killed Iranian military leader Qasem Soleimani.

“A wild card that could further impact natural gas production is the potential for major disruptions to global oil supply,” according to EBW analysts. “…If a major disruption occurs, it could prompt producers with hybrid wells to step up drilling, adding to downward pressure on natural gas even if oil prices rise.”

Another question remains: even under favorable crude economics, how will Permian producers market their associated gas if takeaway remains capped and regional natural gas prices go negative again?

Permian producers have already been leaning on flaring to relieve some of the pressure from constrained natural gas pipeline takeaway out of the region. Raymond James & Associates Inc. analysts led by Pavel Molchanov recently estimated that over the past several years 4% of the world’s gas volumes have been flared annually. Of the estimated 14.3 Bcf/d flared globally in 2019, the United States accounted for about 1.6 Bcf/d.

Domestically, “close to half of flared gas is in Texas, and specifically the Permian Basin, bearing in mind the rapid pace of production growth that has tended to outstrip the buildout of pipeline capacity,” Molchanov said.

While Texas for one has relatively weak regulations on flaring, the decision for Permian producers may not be so clear-cut in 2020 now that fossil fuel companies seemingly find themselves contending with heightened social and political risks amid growing awareness and urgency on climate change.

Cutting back on flared volumes represents a “textbook example of low-hanging fruit” for the oil and gas industry as it faces new pressure from an investment community increasingly focused on environmental, social and governance (ESG) metrics, according to Molchanov.

“Let’s suppose that the site-specific economics in a particular basin are such that operators would prefer to flare. What would stop them?” Molchanov said. “…Some jurisdictions are stricter than others, for a combination of self-interest (maximizing tax and royalty income from production) and environmental considerations (flaring accounts for 1% of global emissions of greenhouse gases, on par with the carbon dioxide footprint of such large economies as Taiwan and Poland).

“And just about everywhere, there is a noticeable shift toward more scrutiny of flaring, in the context of the broad-based political conversations about decarbonization.”

Moving forward, producers might find themselves answering to not only regulators but investors when it comes to flaring.

“Above and beyond the regulatory requirements, oil and gas producers are starting to feel more pressure from ESG investment funds,” Molchanov said. “As a rule of thumb, the highest-weighted component of an E&P company’s ESG score is the carbon intensity of its operations, followed closely by other types of emissions and waste.

“…Simply put, the less a company flares, the better its score will be. When companies are responding to ESG pressure by spending money to reduce flaring, they are not doing it ”out of the goodness of their heart.’ The cash outlays for new equipment and workforce training are counterbalanced by the potential to improve the stock’s valuation by meaningfully broadening the scope of prospective investors.”

Raymond James estimates that the percentage of all U.S. professionally managed assets covered by some form of ESG criteria — 26%, or close to $12 trillion — has tripled since 2012.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |