Regulatory | E&P | Infrastructure | LNG Insight | Markets | NGI All News Access

More NatGas, Less Coal Contributed to Flat CO2 Emissions Growth in 2019, Says IEA

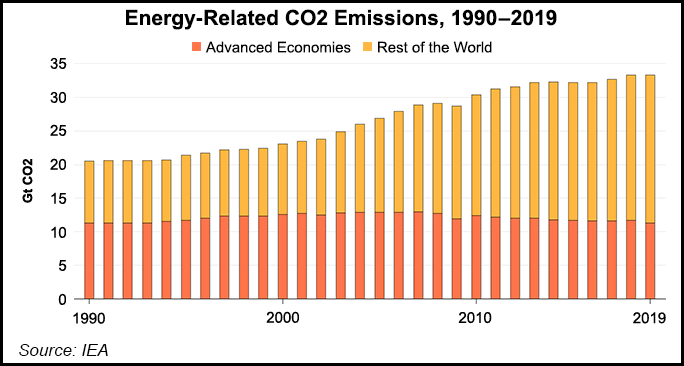

Owing in part to fuel switching from coal to natural gas in advanced economies, global energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions remained flat year/year in 2019, according to new data released this week by the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The IEA estimated that the world’s energy-related CO2 emissions totaled 33 gigatonnes in 2019, unchanged from the previous year even as the world economy saw a 2.9% expansion. Following two years of growth in global CO2 output, the flattening in 2019 emissions defies “widespread expectations of another increase,” according to the agency.

Aside from more natural gas and less coal in the power stack, an expansion of renewables, especially wind and solar, and higher nuclear generation also proved pivotal in keeping CO2 emissions in check as the world’s economic output grew.

“We now need to work hard to make sure that 2019 is remembered as a definitive peak in global emissions, not just a pause in growth,” IEA Executive Director Dr. Fatih Birol said. “We have the energy technologies to do this, and we have to make use of them all. The IEA is building a grand coalition focused on reducing emissions — encompassing governments, companies, investors and everyone with a genuine commitment to tackling our climate challenge.”

Of note in the 2019 emissions trends, advanced economies achieved a “significant decrease” that offset higher emissions in other parts of the world, the agency said.

“The United States recorded the largest emissions decline on a country basis, with a fall of 140 million tonnes, or 2.9%,” the IEA said. “U.S. emissions are now down by almost 1 gigatonne from their peak in 2000.”

The European Union achieved a 5% drop in emissions in 2019, or a reduction of 160 million tonnes. This occurred as natural gas-sourced electricity surpassed coal “for the first time ever” and as wind-powered electricity “nearly caught up” to coal, the agency said. Elsewhere, Japan cut emissions by 45 million tonnes (around 4%), driven by output from recently restarted nuclear reactors. That represents Japan’s fastest rate of decline since 2009.

Among the world’s advanced economies, power sector emissions fell to levels not seen since the late 1980s, even as electricity demand was one-third lower than it is today, according to the agency.

“This welcome halt in emissions growth is grounds for optimism that we can tackle the climate challenge this decade,” Birol said. “It is evidence that clean energy transitions are underway — and it’s also a signal that we have the opportunity to meaningfully move the needle on emissions through more ambitious policies and investments.”

Meanwhile, the rest of the world grew its emissions by nearly 400 million tonnes in 2019; a rise in coal-fired generation in Asian countries accounted for almost 80% of that increase, according to the IEA.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |