Shale Daily | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

More Capital Discipline Should Compel Investors to Rethink E&P Valuations, Says Raymond James

The onshore exploration and production (E&P) industry is tightening up, tilting toward more capital discipline and free cash flow (FCF), which could give investors pause in how they value the group, according to an analysis by Raymond James & Associates.

While still early, preliminary 2018 capital spending plans issued to date “appear to reflect the changing sentiment in the newfound debate between production growth and returns,” said analyst John Freeman in a note Monday.

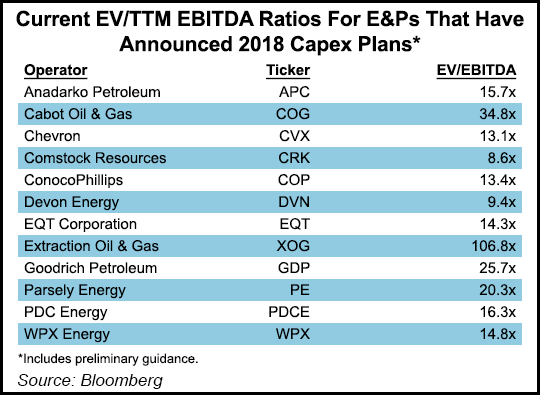

U.S. E&Ps are expected to raise their 2018 capital spending by around 15% over 2017, according to early prognostications. U.S.-based producers that already have set 2018 tentative budgets include supermajor Chevron Corp., super independents ConocoPhillips and Anadarko Petroleum Corp., along with onshore-trained Cabot Oil & Gas Corp., EQT Corp., Extraction Oil & Gas Inc. and Goodrich Petroleum Corp.

Producers often have paid “lip service to the idea of improved capital prudence” but the discipline exhibited to capital budgets “gives us confidence that this time might be different — especially considering the recent discussions around altering compensation structures to be more returns-focused,” Freeman said.

How investors historically have valued the sector has to change as capital discipline becomes the mantra.

“If investors don’t reward companies with lower discount rates and higher multiples going forward then there will be zero incentive for companies to pursue this newfound, capital disciplined strategy,” he said.

As investors become more comfortable with the evolving valuation paradigm these changes may not only offset negative implications from a lower development pace “but also help foster a healthier industry and entice additional capital investment from investors seeking more stable/predictable returns.”

The transition period obviously won’t happen overnight but evolve over several years, Freeman said.

At the end of the day, he said, E&Ps need investor capital, while the “long-only money crowd is almost unanimous in their desire to see returns emerge in this sector that can compete with other industries before sentiment (and capital) can meaningfully improve.”

In addition, the market has to see evidence of E&Ps executing on a successful strategy before the group is valued through a different prism.

Since 2006, about when the unconventional era began for U.S. producers, the sector has outspent cash flow by an average of almost 30% a year, including organic capital spending and land acquisitions, said Freeman.

The outspending has fluctuated dependent on various factors, including commodity prices, but the industry overall hasn’t been close to FCF positive territory over the past decade.

Except for economic/industry downturns, “investors have never really been focused on FCF generation, with the market typically (at least historically) yearning for growth,” Freeman said. Many management teams never prioritized returns-focused approaches to capital allocation, while executive compensation plans generally favored growth too, he noted.

Another explanation that contributed to the overspend relates to the land grab that occurred as the “shale era” kicked off, initially in the Barnett Shale of North Texas during the mid-2000s.

Lots of spending to buy up tracts “yearned back to the Wild West land rush days,” Freeman said, which required years of drilling to hold acreage and ramp up the learning curve with horizontal development.

As many E&Ps shift to a “manufacturing mode,” in which the business plan is making “widgets the fastest and cheapest,” the market should rethink how it values E&Ps, and “the state of the industry should improve meaningfully over the next decade.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |