NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

Miss-Understood Lime ‘Unconventional Conventional’ Play

What explorers know about the Mississippian Lime formation could fill a book. What they don’t know about the Midcontinent play could fill a few more, industry experts said Wednesday.

The best way to describe the potentially 20-million acre formation is an “unconventional conventional,” said Petro River Oil Ltd. Co-CEO Ruben Alba. Thousands of conventional wells already had been drilled hit-and-miss into the Kansas/Oklahoma formation before the unconventional operators began to claim stakes a few years ago. However, there’s still a heck of a lot to learn about the carbonate play, a panel of experts told a packed audience at the Mississippi Lime Congress 2012 in Oklahoma City.

There are a lot of things operators know for sure about the carbonate formation play, which extends from northern Oklahoma into parts of Kansas and Nebraska, even if they haven’t quite settled on a name. The Mississippian Lime, Mississippi Lime, Miss Lime, Mississippian Carbonate — the list goes on. One of its attractions is the cost — it’s a shallow formation at 450-600 feet with low pressure. That means that drilling costs are low — less horsepower is needed to drill. And the costs are a lot less than in some plays: from spud to release, wells cost around $2.5 million.

Are all of the 20 million acres going to be productive? Probably not, said Petro River Co-CEO Daniel Smith, Alba’s partner. “We are able to go in and make good wells.” But some have brought in “8 b/d of oil and 8,000 barrels of water…Others are 1,500 b/d-plus wells. We know they are out there…The beautiful thing about the Mississippi Lime is that it’s not an unconventional reservoir. It’s always produced conventionally and it’s got thousands of wells. It was not fractured…So what we are seeing is a hybrid, an unconventional conventional.”

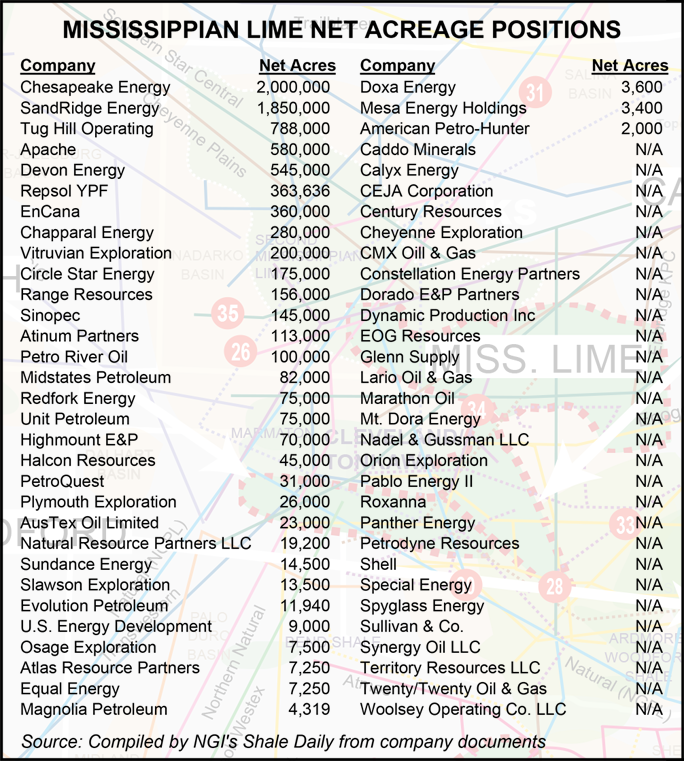

The play has its share of big operators, like Encana Corp., Chesapeake Energy Corp., Apache Corp., Royal Dutch Shell plc, as well as a lot of smaller, family-owned operations (see Shale Daily, Aug. 6). According to data compiled by NGI‘s Shale Daily from company documents, Chesapeake is currently the largest net acreage holder in the play with 2 million acres. Rounding out the top five are SandRidge Energy (1.85 million), Tug Hill Operating (788,000), Apache (580,000) and Devon Energy (545,000).

The carbonate is thick, in some places up to 2,000 feet, which “provides a challenge,” said Roxanna Oil Co. President Julie Garvin. “There’s a tremendous variability through the section. Another variability is in the flow rates. In general, we have seen reported [initial production] rates from 100 b/d to 1,000 b/d…Very variable.”

Even with the uncertainty of what has been reported, large and small exploration and production companies have been undeterred. About 700 unconventional wells now have been drilled, and there are more than 600 active permits, said Garvin. “By my estimates, we can easily expect 10-20 billion bbl of recoverable oil from the Mississippi Lime.”

“It has the source rock but there is extreme lateral variability,” said Garvin, whose company has been exploring the trend since 2007. The play is building by fits and starts using horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, from along the Kansas-Oklahoma border, where the “core horizontal drilling really took off,” and has since moved to the south to the Sooner Trend and east of the Nemeha Ridge. There also is a push to the north, west of the Kansas Uplift.

“If you think about all of the potential extensions, we come up with 20 million acres of potential play areas,” Garvin said. “It’s why there is a conference about a single reservoir.”

Roxanna, which had been looking for a shale play when it began studying the Mississippian, has been drilling into the formation’s Sooner Trend, said Garvin. “We have had wells in the same section, with one well that makes 5 b/d and has 100 barrels of water. And then we have a well with completely different results next to it.”

Looking at the source rocks isn’t enough, she said. Years ago small operators may have drilled deeply into the formation and come up empty. Today, “we are trying to target the highest fracture but the highest in-place resource, laterally and vertically.” A “biggie” for operators is to increase the flow rates through better completion designs. “We are moving away from open hole fractures. These days we are thinking of physics, and the how fluids flow…

“There is a multi-phase flow, with gas, oil and water — three fluid types — all competing for space.” Only now have operators begun to achieve a level of expertise on how far to drill horizontally and how much to fracture the rocks.”

Alba, who formerly worked for Halliburton Co., said “everybody’s going to have a different approach on how to complete reservoirs…The key thing for us is that it is the same geological system, the same migration on a reserves basis.” Whether the Mississippian wells are drilled horizontally or vertically isn’t pertinent. “Both of them are right. We have to derisk the play and some ways to do that are through 3-D seismic,: which might indicate that it’s more important to vertically delineate in one place or horizontally drill in another. “There’s no doubt about it that hydrocarbons are there…It’s a unique characteristic in coming up with completion techniques.”

He told the audience that he’d studied “quite a few reservoirs,” but the “oil in place here is truly tremendous. I wonder what I’m doing in Kansas quite often. But I’m a hydrocarbon hunter and I believe they’re here to be extracted. We are at a point in the industry where we can tackle low-pressure hydrocarbon systems.”

North America’s explorers “did a great job on the shales,” Alba said. “We have gone through the structure in North America in dealing with deep drilling the Utica, the Marcellus…Barnett. Kansas is a very different place with carbonate chemistry and the environment. We don’t realize how much actual reserves there are on the North American continent.

“We know about carbonate chemistry,” as the industry has in the past focused its attention on some formations in the Rockies. “The low-pressure reservoir systems bring their own challenge. They have to be drawn down. That’s what we’re excited about. The water cuts, how to identify the lamination areas, porosity systems that are occurring in saturations over time.”

The Mississippian Lime, Alba said, “is not fully saturated; the oil is sitting on the top and water is on the bottom,” which has confused some of the early drillers. “We have to know how to keep from drilling horizontals in the water systems and we have to stay in the oil systems…”

Early explorers “did what they thought was best at the time,” he said. “There are a lot of hydrocarbons in Kansas,” the first producers, mostly “mom-and-pop producers…just did it very slowly. Given what we know today about the reservoir, we can improve upon it…I believe as an industry we have more gas in the U.S. than we can shake a stick at. But I believe places like this can help us overcome and achieve energy independence. This is a great region to come to develop hydrocarbon reserves.”

The formation can’t be treated the same way as other types of unconventional plays, Smith said. “Some wells, you put a lot of fracks on them like shale wells, and they get better and better. You probably can’t do that here. If you drill too far, you may not make anything and think there’s no oil there. But there is oil there, you’ve got to figure out how to get to it…Those are some of the operational issues we’re dealing with.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |