NGI Mexico GPI | Markets | NGI All News Access

Mexico’s Political ‘Uncertainty’ Said Complicating Natural Gas Market

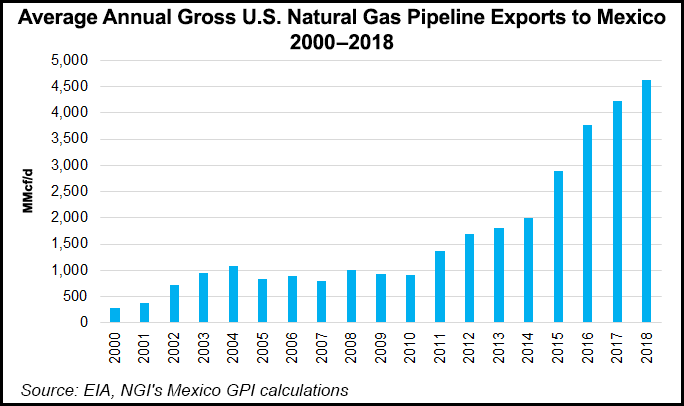

The U.S.-Mexico border is a hotbed for new natural gas pipeline infrastructure to quench growing industrial and residential demand, but “short-term uncertainties” exist, according to experts at the 5th Mexico Gas Summit in San Antonio, TX.

NGI’s Mexico GPI Senior Editor Christopher Lenton moderated the Thursday morning panel, which featured four private sector North American natural gas transportation experts. Sempra Energy’s Brian Lloyd, director of regulatory strategy, was joined by Tenaska Marketing Ventures director Geoff Street, Mexico Pacific Ltd. (MPL) President Josh Loftis and Rosen Group Vice President Jan Frowjin.

The “political considerations” on each side of the U.S.-Mexico border have made the natural gas trade “quite complicated at the moment,” Lenton said. Is there any reason, he asked the panel, to see gas exports from Texas decline under the administration of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a populist who took office last December? The president wants the country to work toward fewer imports.

“In our view, there certainly are new short-term uncertainties,” based on the administration’s “rhetoric and things like that,” Lloyd said. “We have no interest in having pipelines that aren’t flowing gas…But certainly, any time there are discussions around price caps and wholesale regulation there is an additional risk.”

Sempra’s Mexico subsidiary Infraestructura Energética Nova, aka Ienova, is completing the 2.6 Bcf/d Sur de Texas-Tuxpan marine pipeline with TC Energy Inc., which is expected to be online in time for summer when demand traditionally peaks. Sempra also is close to sanctioning a liquefied natural gas (LNG) export project in Baja California, Energía Costa Azul after securing approvals from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). The authorizations would allow Sempra to export U.S.-produced gas to Mexico and re-export the LNG worldwide.

Over the short or long term, it’s difficult to determine if the “value proposition is going to change dramatically,” on cross-border gas trade, said Lloyd, given that the Permian Basin is one of the lowest oil producing regions in the world, and the associated gas has “got to go someplace.

“There is a huge new supply basis in the U.S. at the same time that consumption is declining. There needs to be a home for that…and Mexico as a neighbor has been a great partner…We’re in a populist world, not just Mexico but in the United States…in Europe…”

However, “it’s really hard as a person trained as an economist to think that the value proposition is not there.”

Tenaska’s Street, who said the company moves an estimated 10.5 Bcf/d across North America with marketing affiliates in Mexico, expects gas demand south of the border to increase.

“However…it’s probably not a straight line,” Street told the audience. “It’s difficult when you talk about five years, 10 years into the future.” A “smooth line” for aggregation may be preferred, “but I just don’t know.”

Depending on the “specific rhetoric” pushed by varying factions, “import volumes may not continue to grow,” Street said. But, he said, “There’s certainly plenty of capacity.”

“If the business community is looking at cross-border capacity and 50% is utilized, it’s going to be difficult to make a good business case for infrastructure. Demand should continue to go up,” but it may be in “fits and starts, not a straight line,” Street said.

It’s possible that the level of imports into Mexico “hold where they are,” as it will depend on when pipelines are connected and how much capacity is available. Overall, Street said he thought the growth in imports could be “plus or minus 10%.”

MPL’s Loftis said there “always” would be gas exports from the United States to southern markets, as it would improve downstream markets. “There are different end users” for the imported gas. “I think the more of a mix you have, the more private-public partnerships you have, is a great sign of a healthy environment.”

With DOE export approvals in hand, MPL, like Sempra, is readying an export project near Sonora on the Gulf of California. The facility has the green light to export up to 1.7 Bcf/d for 20 years, with the gas shipped south via existing cross-border transmission lines, including Kinder Morgan Inc.’s Sierrita Gas Pipeline LLC, which extends from the border near Sasabe, AZ, to the proposed 12 million metric ton/year facility.

The privately held partnership’s export project has been “under the radar,” Loftis said. The “recovering import terminal,” as he called it, was nearly to the finish line in 2004. However, the unconventional boom in the United States upended those plans. Now designed to export LNG, the Sonora site is adjacent to a CFE power plant that has been running on natural gas since 2015.

Diversifying suppliers is important, and it’s something that Mexico most likely wants to work toward, Frowjin said. Rosen maintains asset integrity for infrastructure operations around the world, including for oil and gas, and it has two offices in Mexico for pipeline inspections, data quality and integrity management.

“It’s all about how pipelines…get the molecules from A to B,” Frowjin said. The “principle factor is the reliability of the system in Mexico and being able to balance the system and…managing the reliability of the system. That will be a critical factor…how to get from A to B” and do it safely.

The Centro Nacional de Control del Gas Natural (Cenagas), which operates and allocates capacity on the Sistrangas pipeline grid, in March launched the Consulta Publica 2019 to gauge current and potential demand for natural gas. Results of the public consultation are to be used to draft the first iteration of the Cenagas 2019-2024 transport expansion plan.

In May, Cenagas director Elvira Daniel Kabbaz Zaga during a radio interview said preference for gas supply was to be given to state-owned operators Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) and power company Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE), as the energy reform, allowing private investments, “did not improve our lives.”

She suggested Cenagas would maintain oversight of the gas pipelines, including those anchored by CFE.

Given the control that Cenagas may wield over pipelines, Lenton asked the panel if the integrity of the system could be upended. The panelists basically shrugged off the rhetoric, but admitted there could be some issues.

“Balancing the system” to prevent shortages and ensure interconnectivity remains the priority, Frowjin said. Up to now there have been “very few” technical or maintenance issues.

“Very good steps have been made to secure reliability and integrity of the system, and those still are steps that need to be made,” he said.

Street said Cenagas “is quite serious about this…” and “clearly, that’s their intention…” However, there are “compelling arguments for both cases. I can see that having a single manager may create efficiencies, but that assumes the manager will operate in an efficient way.”

The advantage of operators maintaining pipeline systems, as it is done in the United States, is that they are for-profit companies, and there are “financial incentives” and shareholders to which they have to answer, Street said.

The Tenaska executive also is unsure how that could work, as private operators would have to consent, “which I don’t think the government can force legally. There has to be good enough incentives for pipelines to make the switch,” and the changes could impact pipeline infrastructure and “could set the tone for the market on a go-forward basis.”

From a commercial perspective, said Loftis, “it doesn’t matter who operates the pipeline, if there’s consistency and open access,” with clear rules. “That’s what private investment wants to see. Change always has risks, until they know what the change is leading to.”

Asked by Lenton whether community objections to some pipeline projects in Mexico might “scare off bidders” for future projects, Sempra’s Lloyd said the “indigenous issues are real,” and one area that the administration could help smooth would be to facilitate access to get pipelines up and running.

Community protests “are not unique to Mexico,” Lloyd said, giving a nod to the activist groups attempting to impede U.S. pipeline projects.

“Landowner concerns” are something about which U.S. operators are well versed, he said. “There is a slightly different flavor in Texas, but we certainly see it in other parts of the country…the world is somewhat resistant.

People may want more infrastructure “but building it can be very difficult,” Lloyd told the crowd. “The more that government can help mitigate risks, the better.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |