NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | E&P | NGI All News Access

Mexico’s Pemex Slims Corporate Waistline in Restructuring Plan

Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), the Mexican national oil company, is to be given a slimmer look after decades of criticism of its allegedly flabby corporate waistline.

Under a restructuring plan ordered late last month by the Pemex board, four subsidiary companies are to be merged into two. Hundreds of staff are to be dismissed, and many of those who remain will have their salaries reduced. In all, Pemex said in a statement, the resulting savings will amount to 550 million pesos ($29 million) a year.

The upstream subsidiary, Pemex Exploración y Producción (PEP) will absorb the drilling services company Pemex Perforación y Servicios. Likewise, the industrial subsidiary Pemex Transformación Industrial (Pemex Industries) will absorb Pemex Etileno, the ethylene producer.

In addition, the number of departments at Pemex corporate headquarters has been reduced from six to four. The Administration and Services department is to absorb Information Technology. Similarly, the department of Alliances and New Business is to be folded into the Planning and Coordination team.

On the demotion of the department of Alliances and New Business, George Baker of Houston-based Baker & Associates, Energy Consultants, told NGI’s Mexico GPI that he has “assurances from sources inside Pemex that the company has a Plan B to move forward that includes international companies.”

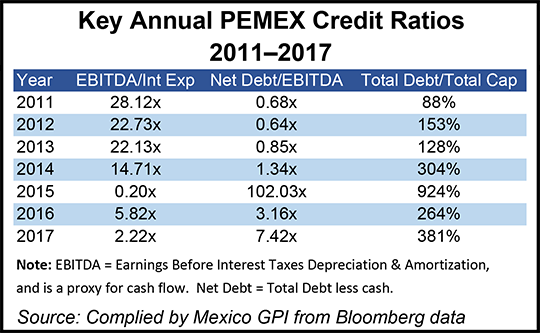

Ramses Pech, a partner in the Tabasco-based consultancy Caraiva y Asociados, is skeptical of the plan’s proposal to cut spending by $29 million. “That’s just a drop in the ocean for a company like Pemex, with its $107 billion debt,” Pech told NGI’s Mexico GPI.

The mergers reflect the urgency in facing challenges in both the upstream and downstream sectors. Arturo Carranza, a Mexico City-based Mercury consultant, said the changes “appear to be a way in which vertical decision-making can resolve in the shortest possible time the problems that Pemex is facing in both E&P on the one hand and refining and gas processing on the other.”

Pemex’s CEO Octavio Romero Oropeza has said that past administrations have dragged their feet in getting projects underway. “The aim now is to reduce the average timespan for implementation from three years to a year and a half,” Carranza said.

Baker recently concluded a study, “Oil Missteps in Mexico 1982-2018,” that covered a period from the financial collapse of the nation in the wake of its oil boom to the conclusion of the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto, author of the 2013 energy reform, a period criticized sharply as the “neo-liberal” era by the current president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

Baker, like many other analysts, has pointed out that successive restructurings coincided with the arrival of each and every government administration. “Restructuring has been politically driven, not a function of the current business cycle,” Baker said.

As a result, Pemex has often been wrong-footed by new trends in the markets, Baker added. “Mexico was not prepared for the shale revolution in the United States. Pemex is still seeking to produce its first barrel of oil from deepwater reservoirs, while, in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico, production from such reservoirs has reached 1 million b/d.”

There have been recurring themes over the years, including corruption. “Moral renewal” was the buzzword of President Miguel de la Madrid (1992-1998), which has an echo of the ethical aspirations, if not the political aims, of López Obrador.

Refinery construction is another recurring theme. Two successive conservative presidents, Vicente Fox (2000-2006) and Felipe Calderon (2006-2012) planned to build new refineries, each of which would have cost $10 billion. The plans, however, were never realized. The current Mexican administration is aiming to build an $8 billion refinery.

The good that could come from the restructuring, Baker said, is that there could be tighter accountability for decision-making by reducing the number of independent departments, folding some into subordinated positions, and, collaterally, justifying the salaries of their directors in the new arrangement.

“A risk for Pemex is the potential for the loss of technical and executive talent as a result of the institutional demotions and salary cuts,” he added.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |