E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI Mexico GPI | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Mexico’s Non-Associated Natural Gas Production Declines, Driving Overall Output Lower

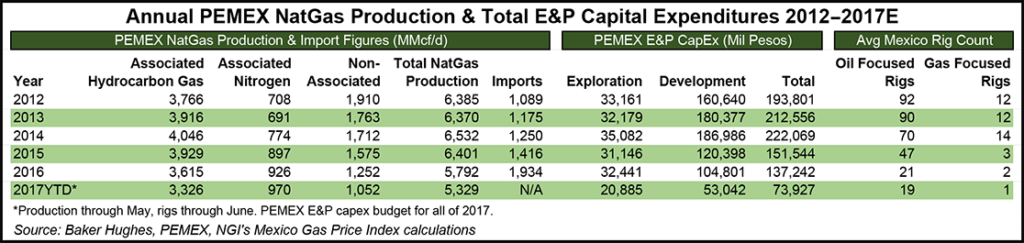

Total natural gas production in Mexico fell at a trendline rate of 3.7% a year between 2012 and the first half of 2017, according to NGI calculations, but that figure obscures the actual driving force behind the overall decline.

Since 2012, associated hydrocarbon gas output from crude oil production in Mexico has fallen by a relatively modest 2.5%/year, dropping from 3.77 Bcf/d in 2012 to 3.33 Bcf/d during the first half of 2017. Meanwhile, non-associated gas production has plummeted since 2012, falling from 1.91 Bcf/d to 1.05 Bcf/d during the first half of 2017. That puts the annualized trendline decline rate at a whopping 11%.

Those annual losses mostly are the result of natural reservoir declines, along with a lack of required capital spending. According to NGI calculations based on Baker Hughes Inc. data, Mexico averaged 92 crude oil rigs and 14 gas-focused rigs in 2012, but those were down to only 19 oil and one for gas in the first half of 2017.

Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) has been starved for capital in recent years and has scaled back its exploration and production (E&P) investments accordingly. In 2014, Pemex spent 222,069 million pesos in E&P activities, which fell to 151,544 million in 2015 and 137,242 in 2016. According to Pemex’s 2016 20-F filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, the budget will be only 73,927 in 2017.

But perhaps nowhere has Pemex’s E&P spending been slashed the most than on its non-associated gas production. The Burgos Basin in northeastern Mexico, the largest producer of non-associated gas in the country, has seen its capital expenditures (capex) fall off an acantilado in recent years.

Pemex devoted 11,695 million pesos to the Burgos in 2012, but it has significantly cut spending in each subsequent year. This year it only plans to spend 904 million pesos there. As a result, Burgos gas production came in at just 865 MMcf/d in 2016, down from 1.27 Bcfd in 2012.

Activity in the Burgos could be on the rebound if Wednesday’s Auction Round 2.2 is any indication. Seven of 10 exploration blocks found bidders in the first upstream auction featuring natural gas since Mexico’s 2014 energy reform.

In view of the current low prices for natural gas, several analysts had predicted that Auction Round 2.2 might be a snoozefest, but the actual auction included fierce bidding on some of the blocks. All but one of the seven blocks receiving bids were in the gassy Burgos.

To help offset its decline in natural gas production, Pemex has ramped up its gas imports in recent years, rising from 1.09 Bcf/d in 2012 to 1.93 Bcf/d in 2016.

Part of the reason for Pemex’s significantly lower capex budget in 2017 is “the promotion of our farm-out program, which we believe will allow us to sustain and increase our production levels while decreasing our corresponding capital expenditures.”

Pemex began that farm-out process in December 2016, when it partnered with BHP Billiton for its offshore Trion block, and with Chevron Corp. and Inpex Corp. in the Gulf of Mexico.

Pemex last Monday also held its highly anticipated “Farmout Day 2017” in Houston, where the company detailed its latest round of tenders.

Pemex is seeking partnership bids for blocks in the shallow water Ayin-Batsil field, onshore Cardenas-Mora Ogarrio property, and the deepwater Nobilis-Maximino holding. Awards for the first two are scheduled for Oct. 4, while the deepwater awards are to come in December, in conjunction with Round 2.4.

Overall, Pemex expects to maintain total natural gas production (including associated nitrogen) above 4.73 Bcf/d in 2017, and so far, so good. The company produced 5.38 Bcf/d in December 2016, and was down slightly in May at 5.30 Bcf/d.

The Burgos Basin is also home to the Mexican portion of the Eagle Ford Shale, and while the shale play could become a source of unconventional investment in time, it may be years before that is the case. In May, one of Mexico’s senior government officials opined that it will be “at least a decade” before there is meaningful development of Mexico’s unconventional plays, particularly the Burgos Basin, which currently suffers from a lack of pipeline infrastructure, access to water and a myriad of security issues.

But as is the case with everything, the decision to develop the Burgos may come down to economics.

“Everything in Mexico, particularly the northern portion of Mexico, will have to compete against U.S. imports, particularly from the Permian and Eagle Ford basins,” said NGI’s Patrick Rau, director of Strategy & Research. “The Eagle Ford is already in full production mode, and unit costs in the emerging Delaware sub-basin in the Permian should continue to come down long-term as that area continues to build out.

“Burgos production will likely have a tough time competing with that, especially since it will start out way up the learning curve.”

Meanwhile, the proposed Sur de Texas-Tuxpan pipeline should be in service in 2018, which would bring in an additional 2.6 Bcf/d of gas from Nueces County in South Texas, providing more gas-on-gas competition for the unconventional Burgos.

Consulting firm Wood Mackenzie in May said its long-term Burgos price assumption is US$3.25/MMBtu, which at a 20% royalty bid, would lead to a company internal rate of return (IRR) of roughly 10%, based on a 100 Bcf gas field, with operating expenses of $3.1/boe and total capex of $145 million. Jack up that royalty assumption to 40%, and the IRR is zero.

“Operators would have a really tough time recovering their cost of capital in that situation,” Rau said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |