Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Mexico Shale Ban Could Hit NatGas Production, Increase Need for U.S. Imports, Says Baker Institute

Banning hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and the development of the country’s vast shale resources could defeat Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s policy aims of limiting natural gas imports, according to an issue brief put together by Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

“Our analysis leads us to posit that whether or not shale development is banned in Mexico, little will change in the near- to medium-term since above-the-ground factors such as limited access to water and a lack of infrastructure are likely to stall shale development,” the paper, published earlier this month, said. “Nonetheless, in the long run, a ban on shale — even if it only stands for the six years of AMLO’s [López Obrador’s] presidency — may have adverse consequences in the absence of an effective scheme to diversify Mexico’s gas supply reserves.

“This is because beyond retarding new production, a ban would shelve the establishment of regulatory and legal frameworks that could encourage shale development… A ban would also impede foreign and domestic investment and innovation, which are both central to shale’s success in the United States.”

Mexico boasts 141.5 Tcf of prospective unconventional gas reserves, according to upstream regulator Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH), compared to 76.3 Tcf of prospective conventional reserves. But López Obrador has been adamant that Mexico will not allow fracking in the country, despite often contradictory remarks from others within his administration.

In December, the CNH cancelled onshore bid Round 3.3, which would have placed on offer nine blocks targeting unconventional gas resources in the Burgos Basin. It would have been the first auction for unconventional acreage in Mexico’s history.

Despite this, as early as last week the Energy Minister RocÃo Nahle’s deputy for hydrocarbons, Miguel Angel Maciel, said that state oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) was still involved in pilot programs. “Pemex has done some test drilling on shale but we need more,” Maciel said.

Indeed, Pemex’s 2019 budget includes 3.35 billion pesos, or about $170 million, for three unconventional pilot projects in the Burro-Picachos, Tampico-Misantla and Burgos Basins, and the CNH has sanctioned fracking at four exploration blocks in Tampico-Misantla.

“AMLO may be keeping the option to abandon his campaign promise if shale extraction could, for example, address his other priorities, including decreasing Mexico’s dependence on foreign energy sources,” the report said. Moreover, “if Pemex cannot meet AMLO’s production goals, the president’s administration would be swayed to resume oil and gas auctions, including those for unconventional oil and gas resources.”

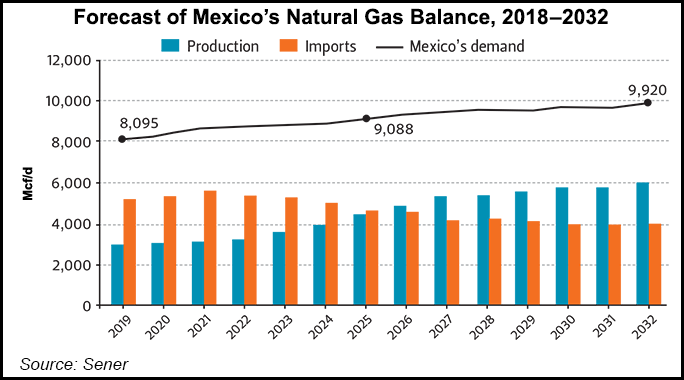

Pemex management has pledged a 50% increase in natural gas output to 5.7 Bcf/d by 2024, but the bulk of the 2019 budget for upstream subsidiary Pemex Exploración y Producción (PEP) is allocated to mature shallow water oilfields off the southeastern coast such as Ku-Maloob-Zaap (KMZ), Chuc, and Cantarell.

Pemex’s production of natural gas has fallen 42% since 2009. Excluding gas demand from Pemex for its operations, imports supplied 89% of Mexico’s natural gas demand in January, according to the CNH.

The report adds that “development of shale in Mexico will not be an easy task, even though the Burgos basin shares geological features with the prolific Eagle Ford in the U.S. This is because the success of shale development in the U.S. is tied to a unique mixture of on-the-ground infrastructure and regulatory and legal factors that, as a whole, cannot be found currently anywhere else in the world.”

These obstacles include who owns subsurface minerals (which in the case of Mexico is the government as opposed to the landowner); the slow process to acquire drilling rights; insufficient regulation related to fracking and water use and disposal; insufficient pipeline, road and rail infrastructure; the limited availability of water in states such as Coahuila; the challenge of ensuring room and board for workers in sparsely populated areas; and the frail security situation which puts into question the safety of workers, equipment and infrastructure.

But “in the long-term, closing the door to shale development deprives Mexico of the potential economic benefits of this unconventional energy resource, including increased employment and investment.

“Even if the shale ban is short-lived, it will postpone institutional capacity-building and industrial development. In addition, Mexico’s import dependency may grow through the build-up of long-term infrastructure, such as cross-border pipelines. Once in place, these are likely to discourage domestic production, which is already bound to be challenged. The ones to profit will be the shale producers who work in the U.S. section of the Eagle Ford and Permian Basins and are happy to dispatch the gas associated with their oil production to Mexico,” the paper concluded.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |