NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Infrastructure | Mexico | NGI All News Access | NGI Mexico GPI

Mexico Pipeline Gas Imports Up 13% In August

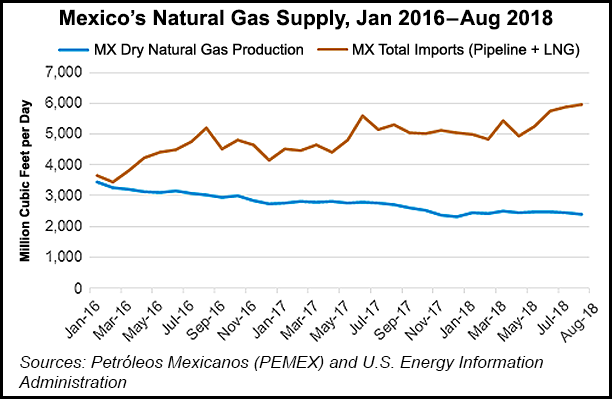

Natural gas imports to Mexico from the United States reached unprecedented levels in August, the Energy Information Administration (EIA) reported Thursday.

Pipeline imports averaged 5.1 Bcf/d for the month, EIA said, up from 4.5 Bcf/d in August 2017. Piped gas accounted for 60% of imports, up from 58% in the year-ago month, with liquefied natural gas (LNG) making up the remainder.

The figures underscore the challenges facing Mexico’s new president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who has pledged to reduce the country’s dependence on imports of refined oil products and natural gas from the United States, and to reverse a precipitous decline in hydrocarbon output that began in 2004 and has accelerated over the last few years.

“Dry natural gas production in Mexico has fallen 38% since 2012 because of declining reserves, a low price environment, and limited exploration and production of new wells,” EIA said, citing that Mexico’s dry gas output fell 7% year-on-year in October to average 2.4 Bcf/d.

The October figure is down 21% from two years ago, EIA said, when production averaged 3.0 Bcf/d.

EIA attributed the 13% year-on-year increase in pipeline imports to the entrance into operation of several new midstream projects, including the Nueva Era and El Encino-Topolobampo pipelines.

In its latest Annual Energy Outlook, EIA forecasts U.S. pipeline exports to Mexico to average 4.7 Bcf/d in 2018, 5.5 Bcf/d in 2019, and 6.0 Bcf/d in 2020, as power sector-driven gas demand in Mexico grows and new pipeline projects on both sides of the border come online.

Despite the inherent risks of depending on a single gas supplier, Mexico is nonetheless poised to benefit from its proximity to the prolific Permian Basin of West Texas and southeastern New Mexico, at least over the near-term.

A gas supply glut in the Permian due to surging unconventional output and insufficient takeaway capacity drove prices in some day-ahead trades in the region into the negatives in recent days, corroborating EIA’s projections of an impending spike in gas exports from Texas to Mexico once the midstream infrastructure constraints are resolved.

“We’ve got an overabundance of natural gas right now,” Mirage Energy CEO Michael Ward told LDC’s US-Mexico Natural Gas Forum in November.

San Antonio, TX-based Mirage is developing the 250-mile Concho-Progreso cross-border pipeline system that will connect the Agua Dulce hub and Banquete header in South Texas to Mexico’s Sistrangas national pipeline grid.

“The fact is the oil and gas producers in the United States need the Mexico market as bad as Mexico needs the gas,” Ward continued. “Whether the politics are there or not, it’s a win-win for both countries.”

Mexico Must ”Carefully Craft’ A Natural Gas Strategy

While the U.S. natural gas bonanza has been driven largely by advancements in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, López Obrador has repeatedly expressed opposition to the latter technique.

This could further complicate Mexico’s efforts to shore up its domestic gas output, given that the country’s prospective unconventional gas resources stand at an estimated 141.5 Tcf, versus 76.3 Tcf of prospective conventional gas resources, according to the Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos.

What’s more, López Obrador has expressed distrust of the constitutional energy reform of his predecessor, Enrique Peña Nieto, which sought to stimulate production by luring private capital to the upstream segment.

López Obrador favors the pre-reform model centered around national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), in which Pemex — which lacks experience in unconventional exploration and production — operates fields and awards drilling contracts to oilfield services providers.

“It is no secret that López Obrador wants to put Pemex at the center of the energy sector in Mexico,” Adrian Duhalt of Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy told NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index in an email.

Duhalt, who is the post doctorate fellow in Mexico energy studies for the Institute’s Mexico Center and Center for Energy Studies, spoke to the energy committee of Mexico’s lower congressional house in November about the risks of continued dependence on imported gas from the United States, and the importance for Mexico’s economy of a strengthened Pemex.

He warned legislators that cheap gas prices north of the border won’t necessarily continue forever, particularly as the United States brings new pipelines and LNG export terminals online.

“That [was] my approach to persuade them to have a broader discussion on fracking,” Duhalt said, adding that if fracking is in fact banned in the end, Mexico’s energy authorities “must carefully craft an alternative strategy to increase production and reduce import dependency.”

Ixachi Field To Supply 700 MMcf/d by 2022

There was, however, some good news last week with regard to gas production in Mexico.

Pemex reported that proved plus probable plus possible oil and gas reserves at the Ixachi field in Veracruz state are three times more than previously thought, and are now estimated at more than 1 billion boe.

The revised estimate makes Ixachi the largest onshore discovery in Mexico in the last 25 years, Pemex said, adding that the field is expected to produce 80,000 b/d of condensate and 700 MMcf/d of natural gas by 2022.

Ixachi has the strategic advantage of being located near existing wells and pipeline infrastructure, Pemex said, which will facilitate a rapid entrance into production.

The hydrocarbons discovered at Ixachi through a recently-concluded exploration campaign by Pemex will ensure the supply of gas to petrochemical plants in Southeastern Mexico, a fast-growing region that suffers from chronic gas shortages.

Given López Obrador’s antipathy to fracking, Ixachi “will surely be part of the solution,” Duhalt said.

Cempoala Compressor Station To Ease Supply Constraints in Southeast

The Ixachi news follows an announcement by national pipeline grid operator Cenagas that work has begun on a project to reconfigure the Cempoala compressor station in Mexico’s Veracruz state, according to national pipeline grid operator Cenagas.

The project, which Cenagas awarded to a consortium of Mexico-based engineering firms in August, will allow for gas imported from Texas via the Sur de Texas-Tuxpan marine pipeline to flow from Cempoala to the Yucatán Peninsula, where the gas shortage has been especially acute.

Gas compressed at Cempoala currently flows to the country’s central and northern regions.

The gas scarcity in southeastern Mexico is due to the area’s isolation from the Sistrangas national pipeline network, and to declining associated gas output in nearby oilfields operated by Pemex.

The marine pipeline, a joint venture of TransCanada Corp. and Infraestructura Energética Nova, is due to enter service by year-end or shortly thereafter, while the Cempoala reversal project is expected to be finished in April.

In addition to gas from the marine pipeline, the reconfigured compressor station will also allow gas imported from South Texas to southeastern Mexico by terrestrial pipelines to reach the southeast.

Greater gas availability in the southeast will allow demand from the industrial, commercial, and power generation segments to be met in the states of Veracruz, Tabasco, Campeche and Yucatán, Cenagas said.

Relief can’t come fast enough for these clients, however, who have been forced to rely on costlier fuel oil to cover the gas supply shortfalls.

In mid-November, José Manuel López Campos, the head of Mexico’s Confederation of National Chambers of Commerce, Services and Tourism, said that the lack of gas supply is a fundamental reason for rising electricity prices.

He said the issue must be solved immediately, and that it cannot wait until the marine pipeline is in service.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |