Regulatory | NGI All News Access

Mexico Needs Help of Private Sector to Improve Oil and Gas Production, Energy Minister Says

Following months of sharp criticism — not to mention tirades and personal attacks — directed by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador against Mexico’s 2013 energy reform and its institutions, Energy Minister Rocio Nahle brought an olive branch to this year’s fourth annual convention of the Asociación Mexicana de Empresas de Hidrocarburos (Amexhi) held last week in the historic center of the Mexican capital.

Amexhi is the private-sector association of oil and gas companies in Mexico, born under the terms of the reform that broke the state monopoly of the energy industry.

Nahle is a loyal lieutenant of López Obrador. The inauguration of such events usually amounts to an exchange of pleasantries, but many of those who gathered for the opening of the Amexhi convention feared a verbal barrage.

The fears, however, were unfounded, Nahle told her audience. The government had no intention of reversing the legislation that enshrines the reform, and the contracts that derive from it, she said. “You have our backing; there is security and there is confidence.”

Nahle underlined the importance of the private sector. “We need to raise production and reverse its downward trend. That’s the challenge and the state can’t face it alone.”

Welcoming Nahle, the Amexhi president, Alberto de la Fuente, recalled that the association’s members have invested $7.7 billion so far in the upstream contracts, with no new ones expected until 2021.

The resulting production amounts so far only to 31,000 b/d of crude, but de la Fuente emphasized that Amexhi members had promised López Obrador they would produce 280,000 b/d by the end of the current administration in late 2024.

The atmosphere during Nahle’s visit was relaxed, but not all was sweetness and light, however. Following the closure of the event, George Baker, president of the Houston-based consultancy Baker and Associates, said “I attended nearly all of the sessions, but I never heard anyone speak the name of López Obrador.”

Given the president’s strong views on energy that have been so frequently expressed, the omission was strange, mused Baker. “People mentioned ‘the government’ or ‘the administration’ but never López Obrador.”

Two prominent participants — Isabelle Rousseau, a senior academic with El Colegio de Mexico, the highly respected research institute, and Alejandra Palacios, the first woman to be president of Mexico’s Federal Commission of Economic Competition — were critical of the current trend of awarding important government contracts without formal tenders.

In December, President López Obrador announced he was suspending all tenders of new upstream oil and gas contracts, including bid rounds 3.2 and 3.3, which would have awarded contracts to develop blocks in the gas-rich Burgos Basin of northern Mexico.

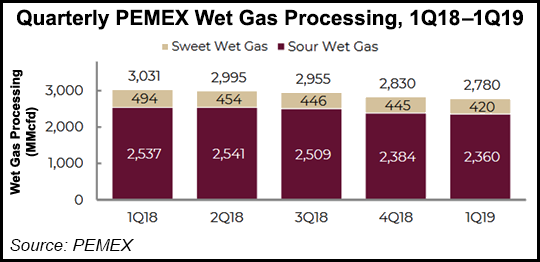

In addition to complaints about the system of awarding contracts, issues of day-to-day business were aired at the event. A participant to the lunchtime forum on private-sector participation in the government’s goals complained that the national oil company, Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), has been charging unfair prices at natural gas processing facilities with holders of contracts for natural gas fields in northern Mexico that were awarded under the reform.

According to the complainant, the same price applies for natural gas processed on both sides of the border, but in Mexico producers do not receive money for the liquids, propane and other elements that accompany the natural gas. The net result is that producers are paid substantially more on the U.S. side of the border.

However, the elephant in the room, as is the case at every business event in Mexico involving natural gas, was the huge but untouched potential unconventional resources the country possesses.

Nahle’s deputy for hydrocarbons, Miguel Angel Maciel, tackled the issue on the day’s final forum. Maciel acknowledged the lack of progress. “Pemex has done some test drilling on shale but we need more,” Maciel said.

“That is nonsense,” David Shields, editor and publisher of the magazine EnergÃa a Debate, told NGI’s MGPI. “There’s been enough test drilling. What is needed is initiative.”

Shale and other unconventional resources require a complete eco-system for their development and there are barriers on the way. “Some are relatively easy — Eastern Mexico has plenty of water, for example — others, like land-holding rights, can be more intractable,” Shields said.

“But drilling is the easy part and it’s already been done.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |