E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Mexico E&Ps Need to Develop Deepwater, Onshore as Era of ‘Easy Oil’ Over, Say Experts

Mexico must unlock its deepwater and unconventional hydrocarbon resources to reverse a decade-and-a-half trend of declining output, according to hydrocarbons undersecretary Aldo Flores.

This means that the country has to continue to attract exploration and production (E&P) investment from the private sector, given that national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) lacks the necessary experience and capital to develop resources on its own, Flores said Monday in interviews with local think-tanks Pulso Energético and the Instituto Mexicano Para la Competitividad (IMCO).

“For approximately 15 years, we’ve been losing 100,000 b/d of production per year,” Flores said. “I’m not saying that production will continue falling at this pace. Pemex has taken great pains to stabilize the fall in production,” which “is due to the maturation of the fields, not a lack of effort by Pemex. But the easy oil is gone.”

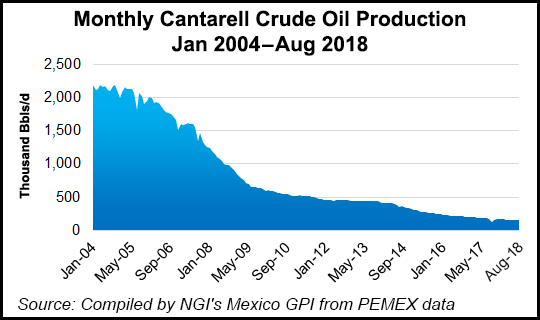

Nowhere in Mexico is the decline more pronounced than in the Cantarell offshore megafield in Campeche Bay, where crude output averaged 158,204 b/d in August, down from 2.2 million b/d in October 2004, according to Pemex data.

While Pemex has historically relied on a single business model for all of its projects, different geologies require different approaches, Flores said. For example, while small to medium-sized independent E&Ps predominate in the North American unconventionals segment, deep-pocketed integrated oil majors lead the way in deepwater, he said.

“So if Pemex is called on to do all this [in Mexico], it would be wise to have diversified partners that allow it to adjust the business model for each project.”

Flores’ comments follow the unveiling of a series of proposals by Mexico’s Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH) to develop the natural gas segment. These include the creation of a state company dedicated exclusively to producing natural gas and a national policy to promote unconventional E&P.

Mexico’s onshore bid round 3.3, scheduled for February but possibly postponed by the incoming government, plans to make available nine blocks targeting unconventional resources in the Burgos Basin, which accounts for a majority of Mexico’s non-associated gas output.

To be sure, Flores and other experts have said enhanced recovery techniques and increased E&P capital expenditure at Pemex’s legacy conventional fields would help to stabilize output levels over the near-term. However, this may not be enough over the long haul.

“Development of deepwater discoveries in Mexico has gone from an option to a necessity to ensure that in the future, Mexico can stabilize its oil production, or even increase it,” Pulso Energético said in a note on Tuesday. “Different forecasts…indicate that, without the development of deepwater, oil production in Mexico will remain at, or even below, current levels.”

Of the 107 contracts awarded through bid rounds so far since the 2013 de-nationalization of Mexico’s oil sector, 27 are for deepwater, the Pulso note said. Additionally, Pemex and BHP Billiton are set to begin delineation and exploration drilling at their Trión deepwater joint venture in 2019.

But Mexico must ramp up the pace and scale of deepwater E&P for the segment to bear fruit, according to Luis Labardini, partner at the Marcos y Asociados energy and infrastructure consultancy.

In an interview last week with Pulso and IMCO, Labardini said that globally about one in 10 deepwater exploration wells end up producing commercially viable amounts of oil and gas. More than 150 deepwater exploration wells per year are drilled in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico, Labardini said, compared to five or six in Mexican waters. “The odds simply don’t work,” he said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |