Infrastructure | Markets | NGI All News Access

Mexico Called Emerging Opportunity for Natural Gas Storage

Mexico’s rising thirst for natural gas, combined with a dearth of production, may translate into compelling greenfield opportunities for storage developers, experts said last week in Houston.

Before the ascent of Lower 48 unconventional development, gas storage was considered paramount in the U.S. onshore to deal with price volatility, often exasperated by weather events and wide pricing spreads in the contract period between January and March. However, the surge in output has led to less need for new projects or expansions.

Operators now are looking elsewhere, including south of the border, according to executives who spoke at the S&P Global Platts’ 17th annual Gas Storage Outlook Conference.

EnerGnostics LLC Managing Director John M. Hopper, who long led projects in the Lower 48, for the past four years or so has been working on storage projects in Mexico. The process, slowed after President Andrés Manuel López Obrador took office Dec. 1, should accelerate again this year, he told the audience.

Some operators are working to build gas storage in Mexico tied to pipeline projects, but storage is not a reality yet. Mexico relies today on the Altamira and Manzanillo liquefied natural gas (LNG) import terminals for system balancing. However, the energy ministry last March published a public policy for storage, which calls for 45 Bcf of inventory by 2026.

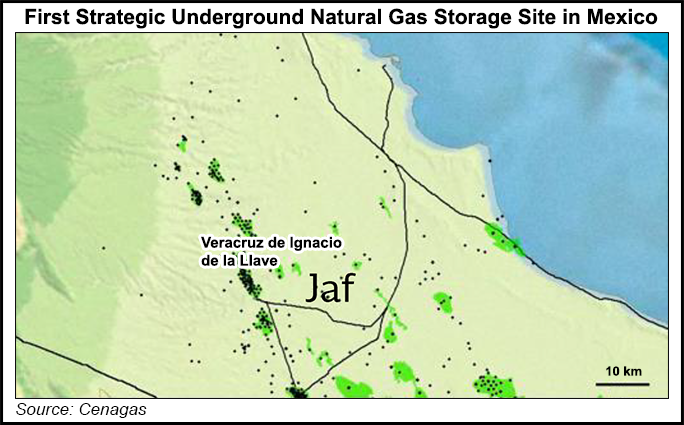

The initial storage construction site nominated for the first 10 Bcf is the depleted Jaf dry gas field. The new administration, however, has not indicated whether the energy ministry will give the order to proceed with the tender.

In Hopper’s view, Mexico’s electric utility Comision Federal de Electricidad, aka CFE, “purposely oversized the pipes relative to what real demand was on those pipes, principally for electric generation, so that they would have room to pack.”

The pipelines could be used as a “surrogate for storage,” he said. “I firmly believe gas storage is needed in Mexico…It will be interesting to see how it shakes out.”

The Jaf field was selected as the first field for storage because it was dry gas, “so they don’t have liquids to deal with,” he said. The field also had been abandoned by Petroleos Mexicanos, the state-owned oil and gas producer. “Technically, whatever reserves may remain belong to the state or people of Mexico. Those reserves have been deemed to be nonrecoverable, so the value is zero.”

LNG Another Possible Avenue

Along with Mexico’s potential possibilities, the growing LNG export trade in the United States may open the door to more storage development. Already there are signs that is happening. The Energy Information Administration reported a 20 Bcf withdrawal from stocks for the week ended Dec. 28. However, a 20 Bcf build in the South Central caught some market observers by surprise, including a 22 Bcf build into salt stocks.

King & Spaulding attorney Jim Bowe, who moderated the panel, said reports have surfaced suggesting “that the impact on salt storage in the South-Central region is related to LNG exports…” Injections into salt storage near the Gulf Coast could be “because LNG activity is ramping up.”

Cheniere Energy Inc. has the only operating export facility on the Gulf Coast now, Sabine Pass in Louisiana, but “several others are coming on,” Bowe said.

Rystad Energy recently noted that the increasing output from the gassy Haynesville Shale in Louisiana and Texas, which is within the South-Central region, has a ready outlet to exports.

In addition, the Dominion Cove Point export project in Maryland “may have implications for storage in the Appalachian region,” Bowe said.

“As more projects come on, we will see an interesting dynamic as people try to figure out who’s going to bear that risk of flowing gas destruction,” he told the audience. Cheniere buys and sells gas, while other planned LNG export projects will use tolling contracts. “I think there’s a bit of a waiting game going on right now.”

Midstream Energy Holdings LLC CEO Scott Smith, whose company is backed by an affiliate of Quantum Energy Partners, said the current outlook for storage “doesn’t paint a positive picture in the near term for greenfield development” unless there is a “unique location or a unique need.”

Mexico is one unique location. Storage for LNG export projects also could make sense.

Added Enstor Gas LLC CEO Paul Bieniawski: “LNG operators recognize they will have process upsets. When it will happen, nobody knows…”

Incidents that would reduce LNG volumes may have a low probability, but if they were to happen, it could have a “high impact,” Bowe said. “It could make things quite constipated on the Gulf Coast very quickly.”

LNG operators using storage “makes perfect sense to me,” Hopper said. The question is figuring out whether adding it makes economic sense. “If I were doing calculations on that, I’d make an educated guess about how many events are going to take place in the timeframe of a year.”

Building a storage facility can cost about $14 million/Bcf for a salt cavern and $25 million/Bcf for a reservoir project, Smith estimated. If the need for storage is low, not many investors would be willing to take a bet on a greenfield project, much less an expansion.

Preceding the unconventional gas boom, U.S. buyers often took 10-year terms for storage, with the expectation they could recontract at similar levels. “That’s not been the case for the last five to 10 years,” Smith said. Buyers today often are only interested in short-term contracts with one-to-three year terms.

The surge in merger and acquisition activity versus short-term rates “indicates no new storage deals in the near term without a physical market need or shifting market dynamics,” Smith said. “Assets are trading hands and trading hands,” but there are few new projects in the works that have been publicly disclosed.

Opportunities Still There

However, Bieniawski argued that opportunities still abound for traditional storage and beyond. The portfolio company of ArcLight Capital Partners owns and operates underground storage facilities on the Gulf Coast and Southwest regions, with net working gas storage capacity of 67.5 Bcf. Facilities access supply to serve growing demand from LNG exports, industrial expansions, power generation and exports to Mexico.

“When there is ever a bubble in the supply, there’s a disproportionate response in the market. That’s an opportunity for gas storage,” Bieniawski said. “LNG, power generation and Mexico are not like traditional U.S. reservoir demand, but that is an opportunity for gas storage for a different set of markets, different set of customers.”

Don’t discount the need for more Lower 48 storage either, Bieniawski said. Some fields are almost 100 years old and they still are being used for gas storage. Some wells are 30 to 40 years old.

“When you add it all together, I don’t think the need for gas storage is going away,” he said.

Updated storage regulations are expected to be issued as soon as Friday by the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA). Safety advisories for storage operators were issued by PHMSA in 2016 for operators to inspect facilities following the extended Aliso Canyon storage leak in Southern California.

“As these rules come through and as LNG sorts itself out and as Mexico sorts itself out, you can make the case for the types of gas storage we’ve had historically,” Bieniawski said.

“Nobody’s talking about gas storage scarcity, but as these regulations roll through, I’m fairly confident that some assets on the North American grid today are not going to be on the grid in the future because they can’t comply with regulations.”

The updated PHMSA rules presumably would impact older assets for the most part, which tend to be in the Northeast and Midwest, and which are held by large pipeline companies. Some of the storage could be taken up by unconventional gas in those areas, Bieniawski said.

There is a “historic opportunity to buy assets at a low replacement cost,” he said. “If you know how to run the assets, there are opportunities out there.”

Many LNG buyers and sellers rely on tolling agreements, under which the buyers secure feedgas for export. That offers an opening for storage. If shippers need a place to park supplies they are committed to buy, what better method than a storage facility?

The “silver lining” is the interest in Gulf Coast storage capacity, Bowe said. The export market is “beginning to present demand for storage services that are unusual and very high…”

Storage contracts to support LNG exports are expected to increase. For tolling customers to make the commitment to gas storage, however, “it’s still early days.”

The name of the game last year was change in ownership for several storage facilities, a trend expected to continue in 2019, Bowe said.

“If asset acquisition activity is any guide, 2018 may end up being the year in which the storage sector began to turn around,” he said. “That activity is what I consider to be the bright spot in the last part of 2018.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |