Lower 48 Oil Boom, Particularly in Texas and North Dakota, Spurring U.S. GDP

The Lower 48 unconventional drilling boom has benefited the nation’s oil trade balance and producing regions, leading to “unusually” large employment and output gains, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Senior research adviser Mine Yücel and senior research economist Michael D. Plante quantified the benefits from the drilling gains that extended to the overall economy from 2010-2015 for the Dallas Fed, as the regional office is known.

Although quantifying the benefits was “difficult,” the researchers used models to estimate that the drilling expansion added as much as 1% to U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) over the period.

They credited Texas and North Dakota for leading growth in domestic oil production and hence, the GDP gains.

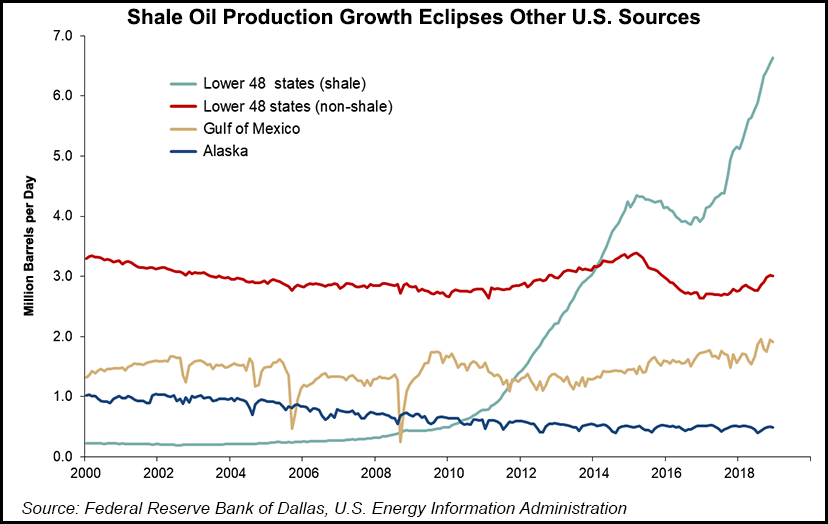

“Since the beginning of 2010, North Dakota’s output has risen from 235,000 b/d to the current 1.4 million b/d. Texas’ crude oil output has climbed from 1.1 to 5.0 million b/d, with the state producing more than half of U.S. shale oil.”

From 2011-2014, when oil prices were averaging $95/bbl West Texas Intermediate (WTI), Texas and North Dakota each experienced strong employment and GDP growth.

“North Dakota’s GDP expansion was 4.5 times that of the U.S., while Texas’ was 1.5 times the U.S. rate,” the researchers noted. “Similarly, North Dakota’s employment growth averaged 5.3% and Texas’ averaged 3.0%, while U.S. employment expanded only 1.7%.”

The surfeit of unconventional oil reserves flowing from 2010-2015 also helped reduce consumer prices overall, they said.

The booming output depressed the benchmark WTI price, with the differential between WTI and the international benchmark Brent widening considerably to a high of $27 in August 2011. The weakness in WTI relative to Brent related to two things: inadequate Permian pipeline capacity, where most of the oil was produced, and the U.S. oil export ban. The ban, a holdover from the early 1970s following the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries’ embargo of 1973-74, was lifted at the end of 2015.

As oil production increased, the ban became an “effective constraint on prices from late 2013 until the restriction ended,” according to Yücel and Plante.

The United States in 2006 imported about twice the oil it was producing, but the share has since declined. As a result, the U.S. petroleum trade balance “narrowed from negative $492 billion in 2005 to negative $136 billion in 2018.”

The researchers employed a “two-country, multi-period equilibrium model describing the decisions and interactions of households, oil producers, refiners and the nonoil production sector.”

They compared the oil industry’s effect on a model economy in 2010-2015 versus what would have happened absent the gains. The boom, they said, caused both oil prices and oil product prices to fall.

“Although refiners amped up output by using a greater amount of their refining capacity, the sheer magnitude of crude production was so high that not all the oil could be absorbed, leading to a significant decline in imports. The decline in imports generated a major improvement in the trade balance for oil, amounting to about 1% of GDP.”

Because oil accounts for most of the marginal cost of producing fuels, including diesel and gasoline, the model also found that the onshore oil boom led to 14% lower fuel prices, not only in the United States but around the world.

“The magnitude of the decline in fuel prices was similar in the U.S. and the rest of the world because, unlike with crude oil, there had been free trade in refined products such as fuels,” the researchers noted.

The model also indicated that the cheaper fuel prices allowed U.S. households to consume about 3.6% more fuel.

“Households also increased their consumption of other goods because the decline in fuel prices increased their disposable income, leading to a 0.7% increase in overall consumption. Altogether, these effects led to a GDP increase of 1% in 2015 relative to 2010,” said Yücel and Plante.

“Given that the actual increase in U.S. GDP was 10%over the period, the shale boom accounted for one-tenth of the overall increase. Although the oil sector makes up less than 1.5% of the economy, our results suggest that the shale boom generated significant positive spillovers.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |