LNG | Energy Transition | LNG Insight | NGI All News Access

LNG 101: Hydrogen’s Potential Impact on Natural Gas Exports

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |

Natural Gas Prices

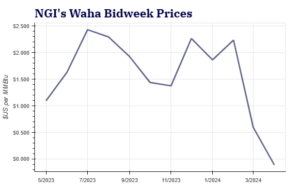

Baseload natural gas prices were trending lower for May delivery as mild weather and a glut of supply in Texas kept bidders from rushing to buy on the first day of bidweek trading Wednesday (April 24), according to NGI’s Bidweek Alert (BWA). In West Texas, Waha traded at fixed prices between negative 44.0 cents and…

April 25, 2024Energy Transition

By submitting my information, I agree to the Privacy Policy, Terms of Service and to receive offers and promotions from NGI.