LNG | International | LNG Insight | NGI All News Access

LNG 101: How Natural Gas Would Be Impacted If Russia Invades Ukraine

The geopolitical standoff between Russia and Ukraine has deepened turmoil in Europe’s natural gas market and laid bare its dependence on energy imports, but it remains highly unlikely that Russia would halt all natural gas flows or even significantly curb deliveries to the continent.

Russia’s Gazprom PJSC “does not need to stop gas to wreak havoc in the European gas market as we’ve seen,” said Anna Mikulska, a nonresident fellow in energy studies at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

Even before Russia massed enough troops on Ukraine’s border for an invasion, Russia had limited spot deliveries and storage injections in Europe. Stocks already were low on the continent, which until recently had to fiercely compete with Asian buyers for liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports in a tight global market. Russia’s moves have “fuelled a lot of the growth in prices that we’ve seen in Europe and a lot of the panic,” Mikulska told NGI.

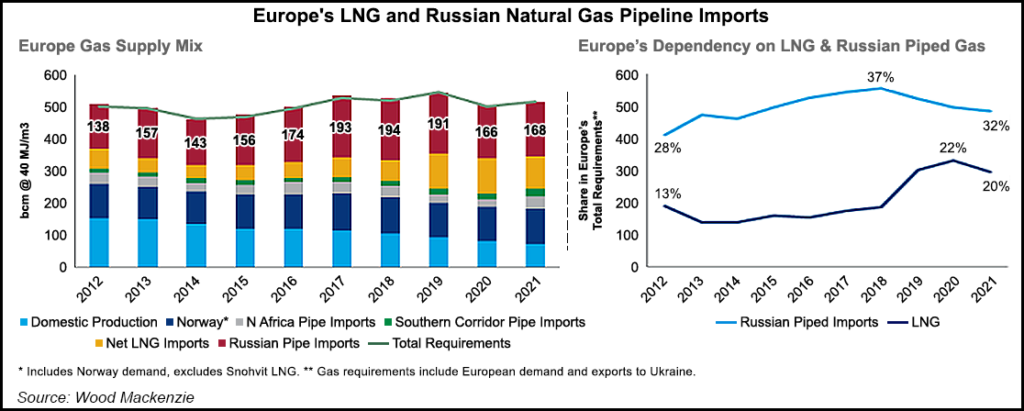

Declining natural gas production in Europe has been the primary culprit for the continent’s heavy reliance on imports, which accounted for 85% of its natural gas supply between 2019 and 2021, according to researchers at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES).

Russian pipeline deliveries were the largest source of natural gas supplies in 2021, accounting for 31% of all imports, OIES said in its latest quarterly gas review. That total expands if Turkey is included, which is a major export market for Russia and a pathway for Russian supplies to Southern Europe, researchers added.

According to OIES, gas moving through Ukraine accounted for 22% of the 168.7 billion cubic meters Russia sent to Europe last year. Russia, however, is not as reliant as it once was on Ukraine for gas transit.

Russia, the world’s largest pipeline gas exporter, has diversified its routes to Europe. It can move supplies to the continent via Belarus, the Baltic Sea, Poland and Turkey if a broader conflict were to impact pipelines in Ukraine, said Andrei Belyi, an energy consultant at Estonia-based Balesne OU.

Belyi told NGI that the potential for conflict between Russia and Ukraine has existed in one way or another since 2014, when Russia invaded and annexed Crimea. He said the likelihood of a full-scale military conflict is low given long-simmering tensions between the two nations. Belyi added that while the intensity of the standoff can shift, “it has never led to full gas flow interruptions via Ukraine.”

Indeed, a complete cutoff of Russian flows is broadly viewed as impractical. Not only does Russia have enough levers to pull when it comes to the geopolitics of energy, but there are also a wide variety of factors that would serve as strong deterrents.

Russia nets billions of dollars on its gas sales to Europe that would be lost if it were to stop flows in any meaningful way, Mikulska said. Such a move also would harm Russia’s reputation as a reliable supplier across the world, and it could cut longer-term demand in Europe if buyers were to replace supplies with other sources or alternative energies in a stronger push toward net-zero emissions, she added.

An invasion could also trigger economic sanctions on Russian natural gas and LNG that would potentially dampen some buyers’ appetite for those supplies, Mikulska said.

Other Options

If Europe is forced to replace Russian natural gas supplies in the event of supply disruptions, it would be tough. Storage inventories are at their lowest level in a decade. Additional pipeline imports from Norway, North Africa and Azerbaijan would be scarce, given the fact that those are already running at or near capacity, OIES noted.

LNG imports would be the primary lifeline, but they’re not enough alone to displace the sheer volume of pipeline supplies from Russia.

“Even if Russian supply is set to hold well below pre-pandemic baselines this year, it would not be possible to fully replace those volumes with LNG,” said James Waddell, head of European gas at Energy Aspects. “Indeed, most of the flexibility to turn down LNG imports outside of Europe has already been used up, so it would be extremely difficult to get more LNG to Europe by persuading Asia to take less.”

Waddell told NGI that the only “real option” to generate more supplies from global LNG terminals would be facilities running above their output design capacity. “But even this excess production would not really cover much of the loss of Russian supply,” he added.

LNG has already been the primary market beneficiary of Europe’s energy supply crunch, particularly suppliers in the United States, which have ramped up deliveries to capture price premiums over Asia.

Europe imported a record 11.6 million tons (Mt) of LNG in January, according to Kpler. Europe imported nearly half of those volumes, or 5.35 Mt, from the United States. Absent the geopolitical standoff, LNG demand is still expected to be strong in Europe this year as the continent would need to replenish depleted inventories when the winter ends.

If supplies are interrupted, and Europe’s gas crisis deepens, the call for LNG would only increase.

“The primary conclusion for investors is that the ugly reality is that a contained conflict between Russia and Ukraine would probably benefit U.S. LNG exporters,” said Evercore ISI analysts, led by Sean Morgan, in a note to clients this month. “The U.S. has a strong alliance of North American Treaty Organization and other global security partners, which constitute conservatively more than 50% of all LNG imports globally.”

Editor’s Note: This segment is one in a series by NGI’s LNG Insight aimed at educating the North American market about the global LNG trade.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |