Regulatory | NGI All News Access

Legal Uncertainties Cloud Mexico Energy Sector’s Consultations of Indigenous Stakeholders

The energy reform has enshrined, for the first time in Mexican law, the right of indigenous communities to be consulted on projects in the electricity and oil and gas sectors, but the process remains clouded by legislative and legal uncertainties.

Resolving these issues, moreover, will likely fall to the next administration as the six-year term of current President Enrique Peña Nieto comes to an end.

“It’s something that is needed, but we don’t believe it will happen this year,” Maria de las Nieves Garcia-Manzano told NGI’s Mexico GPI. She is director of GMI Consulting, a Mexico-based environmental consultancy that specializes in the energy sector. “These discussions and debates in the legislature probably won’t start in earnest until next year.”

Mexico’s new hydrocarbons and electricity industry laws both mandate that the Energy Ministry (Sener) carry out a consulta previa, or prior consultation, to obtain consent from indigenous communities that could be impacted by a project.

Sener has initiated at least 14 prior consultations since the two laws entered force in 2014. However, neither provides much guidance on how those consultations are to be conducted nor on the roles of the different stakeholders, among other things.

“It’s not really clear to anyone what rules should be followed,” Daniela Fernandez de Cordova, managing partner at Impacto Social Consultores, told NGI’s Mexico GPI.

Two documents moving through different branches of the Mexican government seek to rectify the situation. The first is a general law of prior consultation, currently being drafted in the lower house of the Mexican congress. The law would codify the consultation process and formally extend the obligation to other sectors beyond the oil and power industries.

The second document is a set of specific guidelines for consultations on energy projects. Sener is designing the guidelines, although they would also have to align with the general consultation bill in congress. The ministry “has organized numerous workshops that we have participated in,” Fernandez de Cordova said. “There are several drafts out there, but nothing definitive.”

No dates have been set for the completion of either document, but in both cases it appears unlikely that this will occur before Mexico’s presidential elections, scheduled for July 1.

Of the 14 energy sector consultations begun since 2014, five were ongoing as of early April, according to Sener. Among the nine that were finished, eight had secured consent from indigenous communities, the ministry said.

The consultations include processes for the 510 MMc/d Guaymas-El Oro pipeline, built by Sempra Energy subsidiary Infraestructura Energetica Nova (IEnova); for the 670 MMcf/d El Encino-Topolobampo, under development by TransCanada Corp.; for the 886 MMcf/d Tuxpan-Tula pipeline, also being built by TransCanada; and for two exploration blocks in upstream licensing round 2.2, which took place last year.

Results so far have been mixed, according to industry sources. They say the consultation process presents a learning curve for all parties involves — the government, the companies and the communities — one that is not made easier by the continued absence of a solid legal framework.

“In general, I would say the companies are doing a good job, but it is still very new,” Fernandez de Cordova said. “It’s not easy, especially considering that the communities are all quite different.”

Census data indicate that more than 20% of Mexico’s 123 million inhabitants identify as indigenous, a figure than includes diverse and numerous ethnic groups. A federal government agency, known as the CDI, tracks the various groups in a database, although these records are not always up to date.

“We’ve done legal and anthropological studies for projects in areas where, according to the CDI, there are indigenous inhabitants, but when we show up there aren’t any inhabitants at all, much less an indigenous community,” Garcia-Manzano said. “That creates a lot of uncertainty because project developers never really know whether they will need to do a consultation.”

The energy reforms are the first instance of Mexican law explicitly guaranteeing prior consultation of indigenous communities, but the right has existed for decades, at least in theory. Its legal foundations derive from the International Labour Organization’s 1989 Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention No. 169, or C169 for short.

C169, which includes the right to prior consultation on infrastructure and extractive industry projects, has been adopted by nearly every country in Latin America. Mexico ratified C169 in 1990, but its application of prior consultation was spotty before the 2013-2014 reforms.

“Without any domestic law obligating the Mexican state to carry out prior consultations, it was something that occurred only infrequently, usually at the request of a particular community,” Garcia-Manzano said.

In the pre-reform energy sector, most projects were developed by the state energy giants Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) and the Comision Federal de Electricidad (CFE), whose internal protocols did not always match international conventions on indigenous consultation.

Following the reforms, Sener established a unit within the ministry exclusively dedicated to social impact and prior consultation issues. Lacking an established framework, the unit has followed the CDI’s protocols for consulting with indigenous communities. It also operates with a procedural manual that outlines the general steps for a consultation.

Sener determines whether prior consultation is needed based on the findings of a social impact assessment, which is required of all energy projects in Mexico. The ministry’s role is to oversee the consultation process, acting as an intermediary between project developers and indigenous communities.

Companies, in turn, shoulder most of the operational and logistical costs associated with the consultation. These can include consultants, media relations specialists, informational documents and videos, and translations into indigenous languages. Their main role in the process is to inform, although it is not clear, legally or procedurally, whether they can participate directly in the consultation, according to Fernandez de Cordova.

“Something that’s really important, and I think companies have started to realize this, is having a local representative,” she said. “That is, someone who is very, very local — in the state, in the municipality or even within the community.”

The duration of the consultations varies. “They can take two or three months, or they can go on for two years,” according to Garcia-Manzano.

Consultations may get bogged down if a developer fails to carry out proper due diligence and community relations measures from the very start of the project, or when the project involves ejidos, a type of communal landholding that dates back to the agrarian reforms of the 1930s.

“If there is good social management early on and the land involved is not an ejido, the consultation is usually much easier,” Garcia-Manzano said.

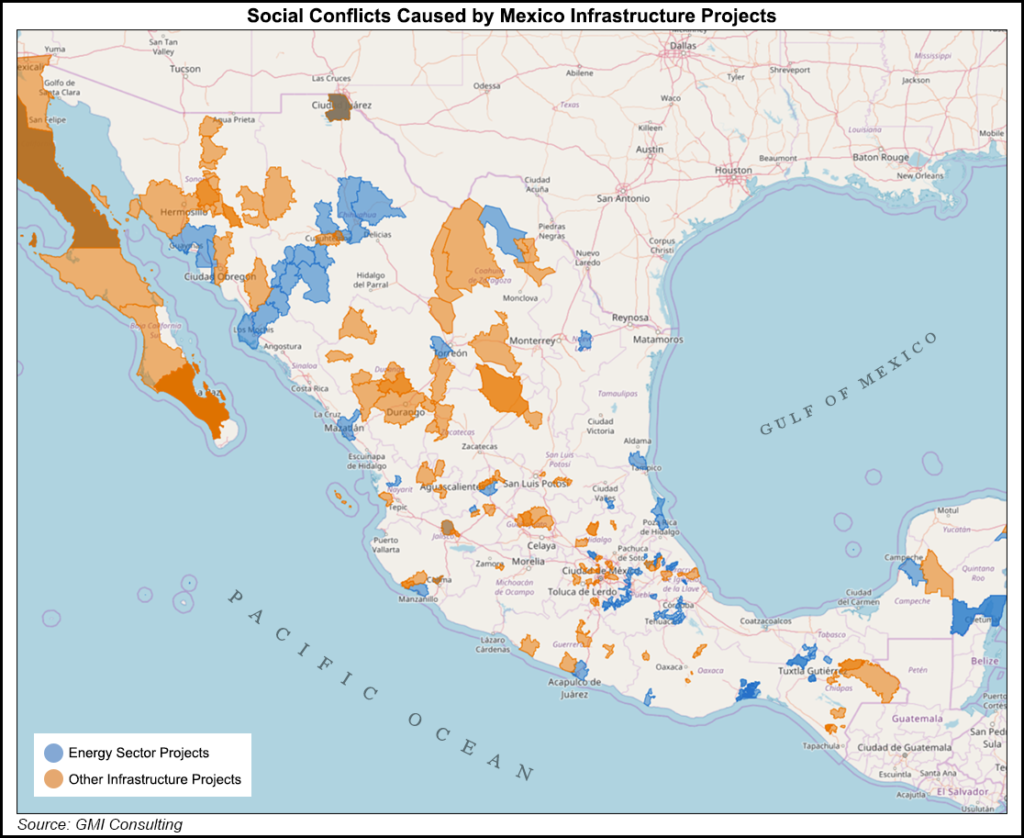

Many pipelines in Mexico face delays related to social conflicts, including the three projects for which there were prior consultations. Industry sources note that these delays does not necessary reflect a flaw in the prior consultation, but rather the legal uncertainty around the process and developers’ lack of familiarity with the complex social dynamics in each community.

The Mexican legal system is also quite “protectionist” when it comes to the rights of landowners, especially for ejidos, according to Garcia-Manzano. In these cases, when judges receive a writ of amparo, a type of legal remedy available to communities and individuals, they immediately issue an injunction on all activity that could be harming the plaintiffs.

“From that moment the project is halted until there is a final decision on the matter, which can take years,” Garcia-Manzano said. “A lot of these pipeline projects have been stopped by a judge’s order.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |