E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

It’s Slow Going on The Upper Devonian, But NatGas is There for The Taking

Long targeted by conventional drillers in the Appalachian Basin, the Upper Devonian Shale formations have been known for some time to hold a cache of dry natural gas. But new technologies, combined with more than a year of close analysis have shown unconventional operators that those six layers of source rock can’t be overlooked.

If anything, the days of being overshadowed by its older cousins in Ohio, West Virginia and Pennsylvania — the Marcellus and Utica shales — are slowly, but surely coming to an end.

Pad drilling and the multiple-pay horizons that it helps facilitate have come to define the U.S. onshore oil and gas industry as of late. The Permian Basin has the Spraberry, Wolfcamp and Cline shales; the Williston basin has the Bakken and Three Forks formations; the Denver-Julesburg has the Niobrara and the Codell shales and the Midcontinent has the nascent Mississippian Lime/Woodford stacks.

But at a time when the Marcellus Shale is growing faster than any other gas field in the country, approaching 15 Bcf/d, and the Utica Shale continues to captivate the attention of onlookers, the Upper Devonian is working its way into the long-term picture.

More data from the formations is pouring in, unconventional development is poised to leave the boundaries of Pennsylvania and more operators are relying on the Upper Devonian to pad their reserves and grow production volumes.

To say the least, the Upper Devonian’s star is quietly rising with little fanfare, and at the bare minimum, it’s a footnote to a much bigger story evolving in the Appalachian Basin. Many, though, believe the formations will play a much bigger part in sustaining that narrative in the years ahead.

“It’s true that companies have been evaluating the Upper Devonian and looking at the intervals for a while now; it’s a shallow, easy target. Here’s the difference where people sometimes get confused: when you talk about multi-play stacked laterals, we’re talking about economies of scale,” said Consol Energy Inc.’s Andrea Passman, director of engineering for gas operations. “You’re adding something that wouldn’t have worked previously on its own. The economics have changed, there’s no separate factors and you’re not incurring the additional costs associated with construction of all those different pieces that burden a well.”

Slow Going

It’s only been within the last two years or so that unconventional operators in the Appalachian Basin began to target the Upper Devonian. Just last summer, the Burkett, Rhinestreet, Middlesex and Genesee began to earn the attention of the news media, as companies released presentations and updated their drilling efforts. In July 2013, both Consol and EQT Corp. announced some of the first completions in the Upper Devonian (see Shale Daily, July 23, 2013). They followed earlier announcements from Rex Energy Inc. in 2011, for example, and Range Resources Corp., which drilled its first horizontal Upper Devonian well in 2009 (see Shale Daily, Sept. 22, 2011).

Matt Henderson, a shale gas asset manager at Pennsylvania State University’s Marcellus Center for Outreach and Research (MCOR), which analyzes state production data on a six month basis, said the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) listed nearly 200 Upper Devonian wells in its cumulative production report for 2013 (see Shale Daily, Feb. 20).

Many of those wells, however, showed nominal production volumes, or were close to stripper status, and nearing the end of their economic life-cycle, he said. Just 28 unconventional Upper Devonian wells were drilled in Pennsylvania last year, according to DEP data. The number is growing, though, with 25 unconventional Upper Devonian wells already drilled this year.

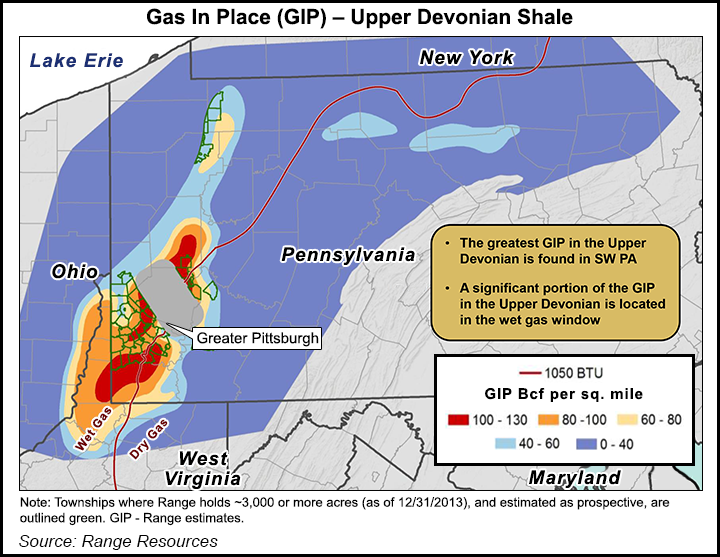

“We have four wells tested so far around our [Washington County, PA] acreage with that dry and wet gas showing itself, and we’re encouraged by the tests we’ve conducted through the years,” said Range Resources’ Joe Frantz, vice president of engineering technology. “One of the things is that we have so much Marcellus acreage to develop and we know the Upper Devonian is there. Once we’re ready to go after it, it’ll be one of those things we co-develop down the road. We’ll have all of our pipeline infrastructure and processing in place for that wet-gas add-on.”

Range spokesman Mark Windle added that the company believes that where the Marcellus is defined by wet or super-rich gas, the Upper Devonian has a similar makeup.

“It’s very similar to some of the numbers we’re seeing from the liquids coming out of the Marcellus. The yields, or how much hydrocarbon liquids are inside the [source rock] are very similar,” Frantz said. “We haven’t drilled enough [Upper Devonian] wells to say that it’s 100% or 75% as good as the Marcellus. We’ll have to develop more and do more testing to find that out, but for now, I’d say the Upper Devonian wells are good enough to stand alone.”

Range estimates that its 560,000 prospective Upper Devonian acres hold 8-12 Tcf of gas and 600-940 million bbls of natural gas liquids. It could be some time before the company has more conclusive data on those unproven resources, though.

For its part, Consol, which has 345,000 prospective Upper Devonian acres, plans to drill more of those wells this summer, Passman said. The company continues to evaluate its acreage and is focused on drilling shallower wells in southwest Pennsylvania on its de-risked acreage.

“We know what the rates of return are for our current projects,” she said. “If it all looks that good then it is something we will spend more on and fully develop, but right now, we’re focused on de-risking our acreage. We’re in de-risk mode.”

Like other companies, Consol couldn’t go into detail on rates of returns because its Upper Devonian wells are included in its test programs. Companies like EQT, for instance, have said during quarterly reports that the Upper Devonian is helping to significantly drive production growth (see Shale Daily, April 25), but little data has been provided on the early results at such wells.

“I wouldn’t expect the number of Upper Devonian wells to be in the 100s [through] 2014 and 2015. What we’re seeing is operators exploring the other formations when they have the infrastructure in place,” Henderson said. “The Upper Devonian results are lower than the Marcellus or Utica numbers — strictly looking at the dry gas production.

“As the operators drill out their acreage and delineate the different formations, I would expect them to drill out the [Upper Devonian] on a production phase in several years,” he added. “They have the acreage secured with their Marcellus and Utica production — so there is no rush — plus with the price of gas where it is, the lower production rates from these wells are more about proving some reserves for their balance sheets and stockholders, as well as future drilling programs.”

Long-term Strategies

Will Green, a financial analyst at Stephens investment bank, which covers Range, said it isn’t yet clear if production from the Upper Devonian could match the rates seen in the Marcellus and Utica shales.

“What it does above all else is add to the inventory-rich nature that the operators can access in the [Appalachian Basin],” he said. “I don’t know if the Upper Devonian economics are going to be really good enough to pinch out the Utica and Marcellus near term. When you’re looking at capital expenditures, the Marcellus and Utica have more favorable economics, but the Upper Devonian does elongate the life of the resource potential and it bolsters the asset base. It doesn’t do anything near term, but it will be a great opportunity in the long-run.”

Range has drilled its Upper Devonian wells fairly close to the Marcellus, testing the formations as deep as 6,500 feet or as shallow as 5,500 feet, Frantz said. The laterals are shorter on its first four wells, between 2,400 feet and 3,400 feet because “we wanted to get comfortable enough with it to the point that you know reasonably how the well is going to perform if we want to upscale to 4,000 or 6,000 foot laterals.”

For now, Frantz said Range is focused on developing its Marcellus acreage, but added that its Upper Devonian program fits in nicely with some of the company’s other exploration efforts in the basin, such as its plan to drill the first Utica well in southwest Pennsylvania this year (see Shale Daily, March 26). He said Range will continue to focus on the Marcellus and return to those pads in the future to drill Upper Devonian wells.

“At this point it looks like the Marcellus is the sweetest spot to drill for Range Resources and it gets the lion’s share of the capital as a result,” Green said. “Some of these companies could make a play out of the Utica or Upper Devonian [in Pennsylvania] given where their acreage sits in that trend. Companies like Range Resources have not seen the best estimated ultimate recoveries that they can on the Marcellus. They’re not yet getting the most bang for their buck and we’ll keep seeing an uplift on the Marcellus. It will be slow-going on the Upper Devonian until they get to that point.”

In the second half of 2013, the MCOR’s analysis of Upper Devonian data showed eight unconventional wells were drilled into the Upper Devonian. Three targeted the Rhinestreet and reported no production, while five wells were drilled into the Burkett. Three of those belonged to the Pennsylvania General Energy Co., and combined, they were only producing about 1.03 MMcf/d. The other two belonged to Royal Dutch Shell plc’s onshore subsidiary and were producing at a combined rate of 429 MMcf/d.

Passman said not nearly enough data on the Upper Devonian formations exists and as Consol remains “really focused on nailing down” its completions program on a formation by formation basis, it will focus heavily on the formations in the coming quarters. Based on that data, the company could simply plan for Upper Devonian wells in the future when it builds a new Marcellus pad, rather than returning to drill the shallower wells at a later date.

Going forward, Passman said it was unclear how important the Upper Devonian would be to the company’s portfolio. Based on early results, some of which she shared with NGI’s Shale Daily, Passman was extremely optimistic about the formation’s potential and added that it is not similar to the Marcellus, as some analysts and other companies have suggested.

She also said there’s even more potential for the Upper Devonian outside of Pennsylvania, in West Virginia, for example, where the formations are deeper than they are in the north.

Structurally-driven

Consol has had one unconventional Burkett well in production for more than a year and what the company has learned from it is surprising, Passman said.

“The Upper Devonian is very structurally-driven and that’s what makes this thing sing,” she said. “It’s different than the Marcellus because of the formation and how the laminated nature of it gives us more natural fracturing and pressure, which are critical to production.”

But therein lies the challenge. As the industry continues to drill more multi-well pads and it targets various formations with stacked laterals, a balancing act ensues.

“There’s a lot of thickness to the Upper Devonian because it’s not just the Burkett. What we see from the stresses of the rock mechanics in the West River Shale and the Middlesex, for instance, you’re getting like 150 to 200 feet of potential pay instead of a smaller package like the Marcellus, which isn’t as thick,” Passman said. “As an industry, we often make the mistake of assuming that what you’ve done in one formation, you can do in another.”

That’s a big reason why Consol’s only producing Upper Devonian well has yet to see a production decline, even though the company had forecast that to happen by now.

“Early on in this industry, what we tend to see, because of shareholders, is a strong value placed on high initial production rates coming out of the gate on most of these wells,” Passman said. “They’re opened right up hard and you might bring back sand that cost a lot of money to put down the well. You also end up pulling so hard from the reservoir to where you reach a point of diminishing returns.”

Passman said Consol chose not to pursue the so-called “grip and rip” strategy and instead opted to carefully manage the pressure of its first Upper Devonian well. Thus far, it has paid off, she said.

But the strategy also highlights a challenge for those in the Appalachian Basin that are trying to develop multiple pay horizons. Passman said pressure management, especially when drilling more than one formation, is crucial.

“It’s pressure from two perspectives. What kind of pressure we use to frack the well, and what kind of pressure we use to deplete it, is critical to the long-term management of the stacked lateral,” she said. “There’s two systems stacked on top of each other, and we’re focused on modeling these tiers in a way that makes them work together in the long-term. If you grip and rip, you’re just going to screw up the pressure pockets. It happens all the time elsewhere and I guarantee you it’s going to happen with others up here.”

Those kinds of complications are currently being worked out and more data from the basin’s stacked formations is expected to be steadily released in the years ahead as the Upper Devonian is further developed. Appalachian operators might “have a high class problem of choosing from three great resources, but they also have to learn how to manage them,” Green said.

Above all, he added, “what the [Upper Devonian] tells you is that part of the country will be producing shale gas for a very long time to come.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |