View more information about the North American Pipeline Map

Background Information about the Eastern Canadian Plays

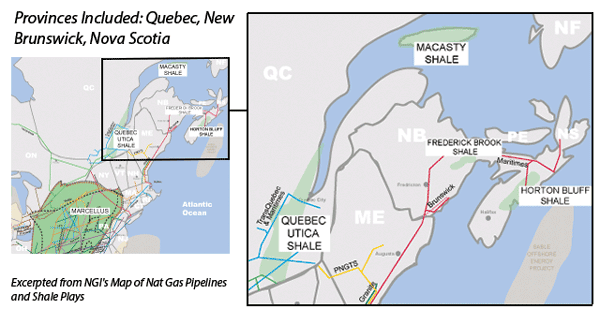

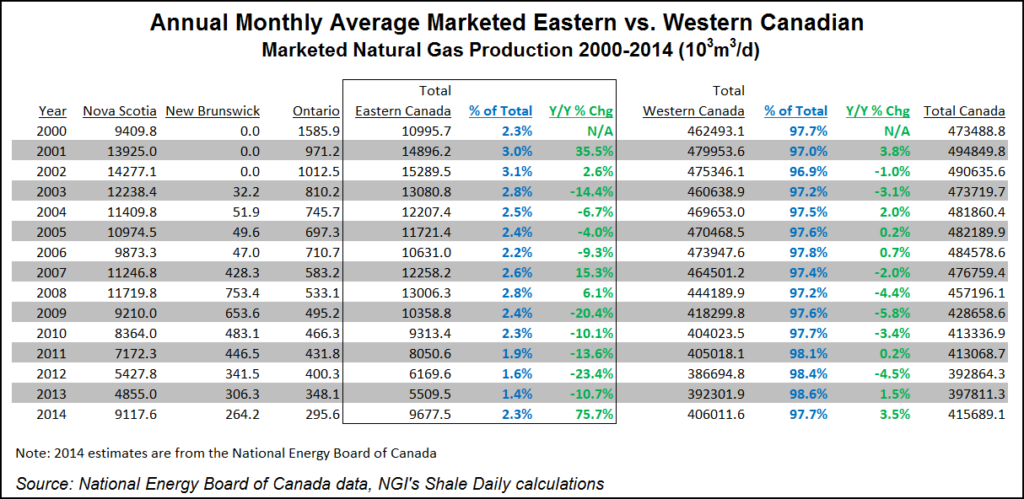

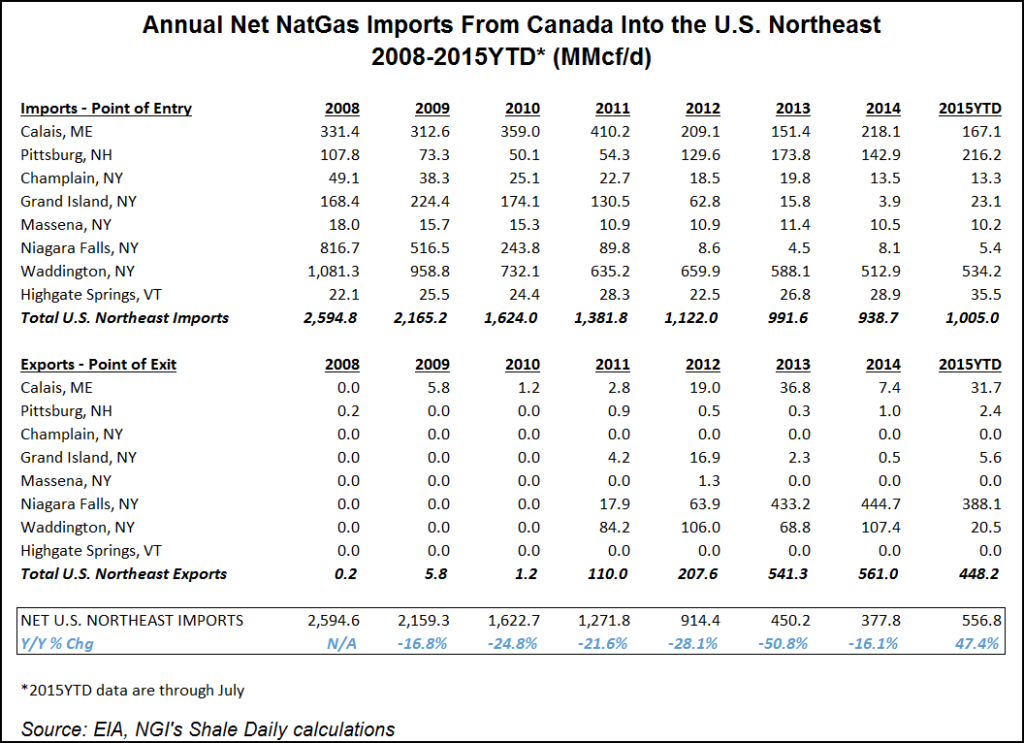

Although Alberta and British Columbia dominate oil and gas production in Canada, the eastern half of the country is not without its prospects, particularly on the unconventional front. The Quebec-Utica, Frederick Brook, Horton Bluff, and Macasty shales have all sparked at least some cursory interest in recent years. The main question, though, is will these properties ever reach full scale development? Eastern Canada faces several challenges that may prevent this from happening, including, but not limited to: 1) bans on hydraulic fracturing (fracking) in portions of Quebec and all of Nova Scotia; 2) decreasing natural gas exports to the U.S. Northeast because of rapidly growing production from the Marcellus and Ohio-Utica shales; 3.) the emergence of the Canaport LNG import facility in 2009, and 4) the potential future development of properties off the shores of Nova Scotia from large operators such as BP plc and Royal Dutch Shell plc.

On the other hand, a downward revised estimate of reserves in the Deep Panuke field off the coast of Nova Scotia in February 2015 by Encana Corp. from 400 Bcf to 200 Bcf (see Daily GPI, Feb. 26, 2015) downgrades the long-term prospects for that facility. Encana put the long-awaited field into service in August 2013, but it was shut down from May through October 2015 because of underground water flow, and Encana now intends to bring it on only during the winter months to capture higher prices (see Daily GPI, Nov. 12, 2015). In addition, a proposed reversal of Canaport to an export facility, along with the proposed Goldboro and Bear Head LNG export facilities and one proposed on the St. Lawrence River by GNL Quebec Inc. — a 25-year export license to load up to 1.55 Bcf/d into tankers at a planned terminal in Saguenay, 210 Kilometers (130 miles) east of Quebec City — would provide potential new markets for Eastern Canadian natural gas production, if these projects are ever completed.

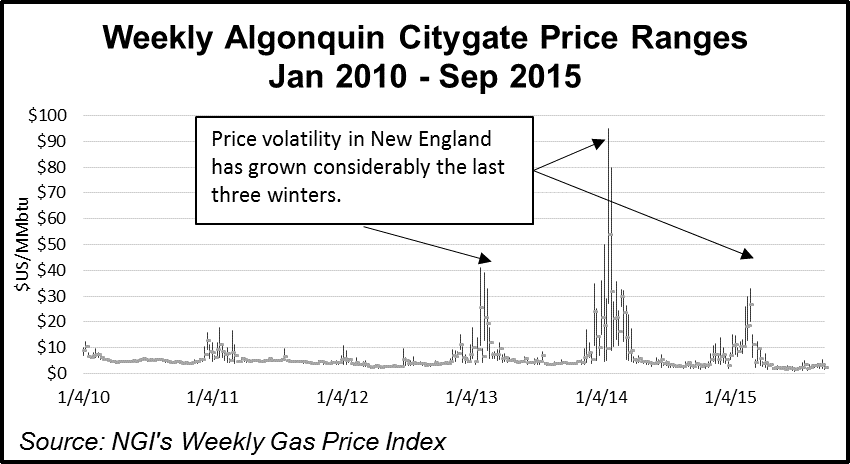

Consumers in New England would love to access more Eastern Canadian natural gas production, especially during the extremely volatile winter months. But that would require more pipeline capacity from Canada, and pipeline construction has been a contentious issue in the U.S. Northeast. However, we do believe that electric generators in New England are making an effort to burn more natural gas, and that would likely require a coordinated effort to increase pipeline capacity in the region.

In October 2015, the National Energy Board of Canada (NEB) estimated that crude oil and equivalent production from Eastern Canada would average 182,920 boe/d in 2015, or 5% of the national total (3.64 million b/d).

We describe each of Eastern Canada’s unconventional plays in a bit more detail below:

Quebec-Utica Shale

Quebec’s history in shale gas development began in 2008, when Denver-based Forest Oil Corp. announced that it had discovered gas from two vertical pilot wells targeting the Utica Shale on its 269,000 net acres in the province (see Daily GPI, April 2, 2008). By 2011, Talisman Energy Inc. had become the largest acreage holder in Quebec’s Utica with 756,000 net acres, followed by Questerre Energy Corp. with 336,440 net acres.

But the outlook for shale development in Quebec began to dim in 2011 as development became a political football. While the Liberal government outlined a new royalty regime in March 2011 (see Shale Daily, March 14, 2011) that would take effect once a two-year strategic environmental assessment of the oil and gas industry was complete, it also decided to restrict fracking for exploration purposes only. In September 2012, the Parti Québécois (PQ) came to power, in part on a campaign promise to shut down shale development. Five months later, the PQ enacted a moratorium on shale gas development and suspended all exploration licenses in the province (see Shale Daily, Feb. 8, 2013). Despite the moratorium, PQ leaders agreed to two joint ventures (JV) between the government and four oil and gas producers (see Macasty Shale) to drill wells on and offshore Anticosti Island (see Shale Daily, Feb. 21, 2014). The Liberals returned to power after elections in April 2014, with Phillippe Couillard as premier. Since then speculation has grown that the province may allow fracking in other parts of the province, although Couillard has been on record as saying he opposes the practice in environmentally sensitive areas. Junex Inc., a junior oil and gas explorer based in Quebec, received a permit in the summer of 2014 to drill its first horizontal well from an existing vertical wellbore near the city of Gaspé (see Shale Daily, July 3, 2014).

Much of the Utica Shale lies under some of French Canada’s oldest communities, which are settled into traditional rural livelihoods, as well as affluent ex-urbanite colonies of families blending modern technical and professional livelihoods with country lifestyles. According to a 2014 report “Strategic Environmental Assessment on Shale Gas: Knowledge Gained and Principal Findings,” or SEA by Quebec’s environmental review board — the Bureau d’audiences publiques sur l’environnement (BAPE) — “shale gas is problematic because of the location of deposits.”

“The shale gas development zone lies in…an area of 34,672 square kilometers [13,175 square miles], composed of 30 regional county municipalities [RCM], 393 municipalities and four areas not in RCMs, the total population being 2.1 million,” the SEA said.

“Nearly 75% of the region is in the permanent agricultural zone and is therefore characterized by farming activities — 43% of the land and 15,878 farm operations — together with forestry operations.”

The SEA added that, unlike U.S. states where shale development thrives, Quebec follows the Canadian pattern of split land titles: private property owners only have surface rights, while underground minerals including oil and gas are public or Crown resources. As a result, no popular interest groups form as development promoters to offset opponents of industrial activity anywhere near their backyards.

The report suggested big changes will be needed to make French Canada welcoming of fracking. “Though it seems unlikely, it cannot be excluded that different economic conditions, new technologies, changes in energy supply and demand, or a change in political leadership, could shift public opinion in Quebec toward a more favorable view of the shale gas industry,” (see Shale Daily, April 8, 2014).

Frederick Brook Shale

The Frederick Brook Shale is a natural gas-rich play in southern New Brunswick. The play, located in the Elgin sub-basin, underlies the tight sandstone rocks of the McCully Field. It also has a total thickness of up to 1,100 meters (3,609 feet) and covers approximately 120,000 acres. According to Corridor Resources Inc. — a junior E&P based in Halifax, Nova Scotia — a resource assessment conducted in 2009 by GLJ Petroleum Consultants Ltd. found that the play holds 67 Tcf of natural gas. GLJ, a Calgary-based firm of independent petroleum engineers, reconfirmed their estimate in 2014.

Corridor jumped into the Frederick Brook in 2009 when it drilled and fracked a vertical well: the Green Road G-41. In December of that year, Corridor and a subsidiary of Apache Corp. — Apache Canada Ltd. — signed a farm-out and option agreement to develop oil and gas resources in the province (see Daily GPI, Dec. 8, 2009). But Apache pulled out of the agreement in May 2011 after it drilled two wells with disappointing results (see Shale Daily, June 3, 2011). Apache backed out after Corridor announced “unexpected and perplexing” results in the Frederick Brook and Corridor has yet to find another partner (see Shale Daily, Dec. 7, 2010). To date, 13 wells have been drilled in the Frederick Brook. According to Corridor, the play is productive from at least six different sub-intervals, spread across a distance of 20 kilometers (12.4 miles). Four wells are currently in production. In May 2015, Corridor shut in most of its producing gas wells in the McCully Field after a dispute over natural gas prices at the Algonquin City Gates. The company resumed production five months later. Corridor said it expects production to average 10.9 MMcf/d (8.5 MMcf/d net) in November and December 2015, followed by 8.4 MMcf/d (6.6 MMcf/d net) for the first quarter of 2016.

The prospects for shale development in New Brunswick were dealt a severe setback in September 2014, after the province’s voters returned the Liberal party to power and turned out the pro-shale Progressive Conservatives (see Shale Daily, Sept. 24, 2014). Three months later, the Liberal government enacted a moratorium on fracking, and said it would not lift it until five conditions were met — the first of which was for oil and gas companies interested in exploring the province to have “social license,” a term in Canada that essentially means the companies have earned the public’s trust in keeping them safe. In September 2015, the province appointed a three-member panel to determine if fracking could be performed to its standards and solicited public comment (see Shale Daily, Sept. 30, 2015). The panel has until March 2016 to present its findings to Premier Brian Gallant.

Despite this, support for shale development in the province could get a boost after the NEB, in August 2015, granted import/export licenses for two liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal projects in neighboring Nova Scotia, and one in Quebec, all of which could draw some of their natural gas supplies from onshore Canadian production (see Daily GPI, Aug. 17, 2015; May 26, 2015). Goldboro LNG, a project sponsored by privately-owned Pieridae Energy Ltd., received a 20-year license for its proposed 1.6 Bcf/d plant near Halifax, NS, while Bear Head LNG Corp. and Bear Head LNG (USA) LLC were given a 25-year license for a proposed 8 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) export facility on the Strait of Canso in Nova Scotia. GNL Quebec Inc. also received a 25-year export license to load up to 1.55 Bcf/d into tankers at a planned terminal on the St. Lawrence River 130 miles east of Quebec City (See Daily GPI, Aug. 28, 2015).

In 2010, Southwestern Energy Co. was awarded an exclusive license to conduct a three-year exploration program on 2.5 million net acres in New Brunswick by the Energy and Mines Ministry. In exchange, the Houston-based company was required to invest C$47 million in the province, with the deadline extended to March 31, 2016. During a 3Q2015 earnings call in October 2015, President Bill Way said Southwestern was marketing a package that includes its acreage in New Brunswick and other plays as it searches for a potential JV partner.

Horton Bluff Shale

The U.S Energy Information Administration, in a 2013 report on the world’s shale formations, estimated that the Horton Bluff formation — part of the Windsor-Kennetcook Basin — held 3.4 Tcf of technically recoverable natural gas. In a 2014 white paper commissioned by Nova Scotia’s provincial government, researchers from Cape Breton University said the extent of the Horton Bluff was “poorly understood,” but said the best estimate was 520 square miles. They added that the play’s thickness ranged up to about 150 meters (492 feet). But development of the Horton Bluff has been out of reach since April 2011, when Nova Scotia first enacted a ban on fracking (see Shale Daily, April 12, 2011). The ban has been in place ever since, with renewals in 2012 and 2014 (see Shale Daily, Sept. 30, 2014; April 23, 2012).

Development of Nova Scotia’s shale formations began before the ban, in 2007. At that time, Denver-based Triangle Petroleum Corp. acquired an interest in the Windsor Block through a farm-in agreement with Contact Exploration Inc. Between May 2007 and March 2009, Triangle performed 2D- and 3D-seismic testing in the Windsor Block and drilled and completed five vertical test wells. The company executed a 10-year production lease with Nova Scotia in April 2009, agreeing to drill seven wells by April 15, 2014, to retain its rights to conventional oil and gas and shale gas in the area (see Daily GPI, April 17, 2009). Areas not drilled or evaluated after the fifth year of the agreement were subject to surrender. However, as a result of the regulatory uncertainty and bans on hydraulic fracturing, Triangle had fully impaired its more than 400,000 net acre position in Nova Scotia as of January 31, 2013.

Macasty Shale

The Macasty Shale underlies Quebec’s Anticosti Island, a sparsely populated, 7,923-square kilometer (3,059-square mile) island located at the point where the Saint Lawrence River empties into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. According to Corridor, the Macasty is “a black, organic-rich shale with similar geological characteristics” to the Utica-Point Pleasant interval in Ohio. Corridor came to that conclusion after it analyzed about 900 samples it took from three test wells it drilled on the island with Pétrolia Inc. in 2012.

Despite the aforementioned moratorium on fracking in Quebec, the provincial government finalized an agreement to develop oil and gas resources on the island with Corridor, Pétrolia and a third company, Saint-Aubin E&P (Québec) Inc., in April 2014 (see Shale Daily, April 8, 2014). The agreement created Anticosti Hydrocarbons LP (Anticosti LP). Under the arrangement, Saint-Aubin E&P and a provincial government entity, Ressources Québec, agreed to invest $100 million in two phases for exploration efforts, with the former investing $43.3 million and the latter $56.7 million. Resources Québec was to hold a 35% interest in 38 licenses on the island, while the three remaining stakeholders were to each hold a 21.7% interest. The first phase of the project called for drilling 12 core holes between 2014 and 2015, followed by three horizontal exploration wells in the summer of 2016. Additional wells could be drilled after 2016. In 2011, consulting firm Sproule Associates Ltd. estimated that the Anticosti JV acreage held 33.9 billion boe of unrisked, undiscovered petroleum initially-in-place. The firm lowered its estimate to 30.7 billion boe in April 2015. Anticosti LP announced in October 2015 that it had completed the first phase of the project within budget, and would identify locations for the three horizontal wells within weeks. The agreement has not been without its critics; a coalition of environmental groups opposed to shale gas drilling on Anticosti Island blasted the government for not being forthcoming with the results of geologic samples taken from the island, and for taking an inconsistent stance on climate change.

In October 2014, Anticosti LP signed a strategic agreement in principal with Gaz Métro Limited Partnership to develop associated natural gas from Anticosti Island. Under the agreement, Gaz Métro, the largest natural gas distribution company in Quebec, will provide the partnership with technical expertise in transporting associated gas to market, should any be produced. In exchange, Anticosti LP agreed to an exclusive partnership with Gaz Métro for five years. “There are a variety of technical issues to address, including storage, transportation, and distribution of the gas,” Gaz Métro said, adding that it will “have acquisition rights to any natural gas produced from wells on Anticosti Island and be able to transport or distribute it to the markets, at a price that will allow its marketing while taking into account prevailing prices.”

Provinces

Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia

More information about Shale Plays:

Utica | Permian | Bakken | Tuscaloosa Marine Shale | Haynesville | Rogersville | Montney | Arkoma-Woodford | Barnett | Cana-Woodford | Eaglebine | Duvernay | Fayettville | Granite Wash | Horn River | Green River Basin | Lower Smackover / Brown Dense Shale | Mississippian Lime | Monterey | Niobrara – DJ Basin | Oklahoma Liquids Play | Marcellus | Eagle Ford | Upper Devonian / Huron | Uinta | San Juan | Power River | Paradox

Shale Daily

Shale Daily